RAF ENDS GERMAN BATTLESHIP TIRPITZ’S CAREER

Tromsø Fjord, Occupied Norway • November 12, 1944

On this date in Norway’s Tromsø Fjord the British Royal Air Force dropped 3 “Tallboy” 13,000‑lb/5,897‑kg bombs to capsize the German battleship Tirpitz, the Kriegsmarine’s ill-starred wannabe surface raider. Ever since September 22, 1943, when a pair of Royal Navy midget submarines engineered a hair-raising daylight attack on this Bismarck-class battleship, the largest, once most powerful warship in the world lay impotent at anchor awaiting her end on this 12th day of November 1944.

Tirpitz had been in British crosshairs long before she was commissioned into the German fleet in February 1941. Since 1942 the 42,000‑ton battleship rarely ventured from lairs deep inside Norwegian fjords where she took station. When she did slip out of her ice-clad fortresses, her only successful venture came in September 1943 when, in concert with the German battleship Scharnhorst, Tirpitz used her 8 15 in./381 mm and 12 5.9 in./150 mm gun batteries to bombard a British weather station on Norway’s Arctic island of Spitsbergen. Sadly for Tirpitz, the warship was scoreless on the 2 occasions she assumed the mantle of surface commerce raider intercepting Allied merchant convoys to and from the Soviet Union. Countless shore batteries and antiaircraft guns and antitorpedo nets at various anchorages in Norwegian fjords tended to protect Tirpitz from the wrath of British air and naval forces. That said, British midget submarine and air forays in 1943 and 1944 breached German defenses on 5 occasions with the intent to damage the “Lonely Queen of the North” until the RAF’s triumphal November 1944 Operation Catechism dispatched her to a watery grave.

With the demise of Tirpitz, which was the Kriegsmarine’s next-to-last remaining capital ship, Grand Adm. Erich Raeder’s grand folly, Plan Z, came to an expensive and inglorious end. That plan envisioned sets of fast German surface commerce raiders running amuck among the Allies’ Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific merchantmen. At the start of the European conflict in September 1939, Germany’s enemy, Great Britain, needed about 55 million tons of overseas imports per year—food, oil, cotton, wool, and other vital consumer and industrial products—to sustain the fight. Raeder’s goal was to sink more tonnage than Britain could endure or replace, thus forcing her surrender before the war potentially drew in new belligerents on Britain’s side.

Raeder focused primarily on his powerful raider fleet of 10 expensive, “late-model” capital ships to cut Allied sea-lanes—this to the detriment of his large underwater fleet of U‑boats. In material and manpower costs alone, a Bismarck-class warship cost 10 times the cost of one U‑boat. Leading Raeder’s armada were the new battleships, the heavily armed and armored Bismarck and Tirpitz, followed by battlecruisers (actually battleships) Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, “pocket battleships” (reclassified as heavy cruisers) Deutschland (renamed Luetzow in 1940), Admiral Graf Spee, and Admiral Scheer, and the Admiral Hipper-class cruisers, Hipper, Blucher, and Prinz Eugen.

As the war expanded in 1942 with America’s entrance, the Allies employed cryptanalysis and introduced aviation and maritime technological advances to combat surface and underwater enemy fleets; e.g., long-range patrol aircraft and radar and sonar. Raeder’s successor, Grand Adm. Karl Doenitz, was gradually confronted with mounting fleet losses even as the Royal Navy’s capital ship assets were stretched to the breaking point protecting Allied shipping from the potential menace of German surface raiders. Total tonnage sunk by the Adm. Raeder’s surface raiders was just short of 800,000, a pittance compared to the 14.1 million tons (2,779 ships) Doenitz’s U‑boats sent to the ocean bottom in all theaters of the war.

Taking Out the Tirpitz

|  |

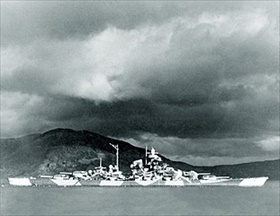

Left: Tirpitz anchored in Bogen Bay near Narvik, Northern Norway, 1943–1944. The battleship is protected by antitorpedo nets, a defense against British torpedo bombers and miniature submarines. Artillery batteries and antiaircraft guns dotted harbors and mountainsides at multiple Norwegian anchorages to provide additional defenses against British 2- and 4‑engine bombers and carrier aircraft.

![]()

Right: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was obsessed with taking out Tirpitz (“the Beast” as he called the battleship) owing to the costs of keeping Britain’s guard up in the seas west and north of German-occupied Norway. “The greatest single act to restore the balance of naval power would be the destruction or even crippling of the Tirpitz,” Churchill wrote. “No other target is comparable to it.” On April 3, 1944, the Royal Navy put a second down payment on Tirpitz’s fatal demise later in the year when carrier aircraft dropped heavy- and medium-sized bombs on the battleship at her anchorage in Alten Fjord (Operation Tungsten) in Northern Norway (shown here), the first of 5 bombing raids that ended with RAF Bomber Command sinking the Tirpitz on November 12, 1944. The April 3 Navy raid killed over 100 crewmembers and wounded 300 or more but only damaged the battleship’s superstructure. No bombs pierced her armored deck. An attack on Tirpitz the previous September by 2, possibly 3 British midget submarines (X‑craft) had rendered the battleship unfit for combat—forever it turned out.

|  |

Left: A prototype X-craft churns along during sea trials prior to Operation Source, the Royal Navy’s September 22, 1943, attempt to cripple or sink the Tirpitz in its berth in Kaafjord, Northern Norway. Six of these 51 ft./15.5‑meter, 30‑ton, 4‑man midget submarines were specifically designed to attack naval targets in strongly defended anchorages. In lieu of torpedoes each midget sub was fitted with 2 crescent-shaped detachable explosive charges attached to either side of its pressure hull. These mines, each containing 2 tons of Amatex explosive, were to be planted in the seabed directly under the Tirpitz, then detonated with a variable time fuse. Three out of 6 X‑craft reached their target. Explosions underneath the Tirpitz tossed the warship’s 4 main turrets from their roller-bearing mountings, gashed and distorted her hull, rendered all 3 engines inoperable, and put the port rudder and all 3 propeller shafts out of order. Out of action for at least 6 months Tirpitz was sunk in Tromsø Fjord on November 12, 1944, by a British force of 32 Lancaster bombers. Approximately 200 seamen survived, while between 950 and 1,204 perished.

![]()

Right: Tirpitz lying capsized in Tromsø Fjord attended by a salvage vessel (dark shape in background). The towering battleship, already damaged in 5 raids, was finally sunk in Operation Catechism, a daylight raid by 2 RAF squadrons of 4‑engine Lancaster bombers on November 12, 1944. Flying through the battleship’s 15 in./381 mm cannon and anti-aircraft fire, the Lancs managed to drop their Tallboy bombs, some scoring hits, others near misses. A deck fire caused the magazine for the “Caesar” (stern) turret to explode, and the great ship, already destabilized by direct hits and close calls, slowly heeled over on her port side and capsized. Of Adm. Raeder’s 10 capital warships in early World War II, only the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen survived the conflict. Transferred to the U.S. Navy as a war prize, the warship ended up in the Pacific, serving as fodder for 2 atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. On December 22, 1946, Prinz Eugen capsized and sank in the Kwajalein Atoll.

Well-Done Documentary on the Career of Tirpitz, 1936–1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click