RADIO STATION HIT, HITLER VOWS REPRISAL

Berlin, Germany · August 31, 1939

On August 22, 1939, Adolf Hitler told his generals he would fabricate a story to justify his planned aggression against neighboring Poland. The plan was for Nazi Party Schutzstaffel (SS) operatives to dress in Polish uniforms, attack a German customs post and a German radio transmitter station in Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia (today’s Gliwice, Poland) on what was then the border between the 2 countries, and broadcast an anti-German diatribe in Polish. To make the whole thing realistic, “casualties” were needed. So 6 concentration camp inmates were dressed as Polish soldiers and shot at the customs post by Germans “returning fire” to suit the storyline. A German Silesian, arrested by the Gestapo the day before and dressed to look like a Polish saboteur, was murdered via lethal injection, shot several times for appearance sake, and dumped at the radio station.

These cold-blooded murders to fool world opinion, which occurred on this date, August 31, 1939, were a fitting opening to mass murder on an unimaginable scale. The next day, September 1, in “retaliation” for Polish “frontier violations of a nature no longer tolerable for a great power,” German troops and tanks “counterattacked” across the 1,400‑mile/2,253‑km border, slicing through Polish resistance like a hot knife through butter, while overhead Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe murdered people one Polish town and city at a time.

World opinion refused to buy into Hitler’s wicked farce as he and his foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, had hoped. Hitler’s bestial nature, which he had cultivated and celebrated in public and private for 2 decades, was evident to every European statesman who had ever tried using peaceful measures to collar and tame the Nazi beast. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who had seen Hitler up close on a half-dozen occasions, described the man as “the blackest devil he had ever met.” Violence, racial hatred, bluff, bad faith, inflammatory propaganda, menacing threats, and a lust to murder on an international scale were hallmarks of Hitler’s true character. The testy scene between British ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson and Ribbentrop on August 29, when Germany made new demands to end the crisis over the status of Danzig and the Polish Corridor, had been over the top—and the best evidence that German leaders never truly contemplated a genuine settlement. With resignation Chamberlain and his French counterpart, Premier Édouard Daladier, embraced the gruesome future and declared war on Nazi Germany on Sunday, September 3, 1939.

Two Principals in the Gleiwitz Charade

|  |

Left: The Gleiwitz Incident, a mock Polish attack on German soil, was the brainchild of arch-criminal Reinhard Heydrich (1904–1942), shown here in 1940 as an SS-Gruppenfuehrer. Heydrich was deputy to Reichsfuehrer-SS Heinrich Himmler and head of the Gestapo (Secret State Police). The “Butcher of Prague,” as Heydrich later became known, was mortally wounded in late‑May 1942 by 2 Czech nationalists. The Heydrich-devised Gleiwitz Incident was approved by Hitler, who had requested the SS stage an event that had the appearance of Polish aggression against Germany to help him justify the Nazi invasion of Poland.

![]()

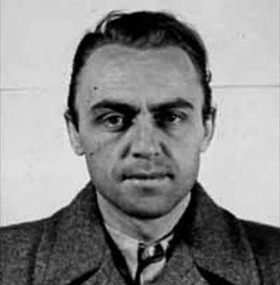

Right: Just one of twenty-one similarly manufactured events that Hitler quickly attributed to Poles, the Gleiwitz Incident was mounted by SS officer Alfred Naujocks (1911–1966), shown here in a 1944 U.S. Army mug shot. A serial killer not quite in Heydrich’s league, Naujocks in late 1939 had provided the Gestapo with an uncoded list of Britain’s intelligence agents throughout Europe, an espionage coup so catastrophic and deadly for the British that Hitler himself pinned the Iron Cross on Naujocks’ dress uniform at a ceremony in the Reich Chancellery. Naujocks moved on to engage in sabotage and terrorist actions against Danes from December 1943 to autumn 1944. Before that he allegedly was involved in the deaths of several members of the Belgian underground. In October 1944 Naujocks was detained by U.S. servicemembers as a possible war criminal and spent the remainder of the war in detention. He testified at the postwar Nuremburg trials about his role in the Gleiwitz charade, sold his account to the media, and moved to Hamburg, where he became a businessman.

German Preparations for the Invasion of Poland: Staging the Gleiwitz Incident

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click