PRESIDENT SIGNS BILL TO REDRESS WARTIME WRONG

Washington, D.C. • August 10, 1988

On this date in 1988 U.S. President Ronald Regan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Regan’s signature corrected a wrong that occurred when another American president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, issued Executive Order 9066. The February 19, 1942, order directly led to the exile and incarceration of more than 120,000 civilians of “enemy” (i.e., Japanese) ancestry in U.S. confinement camps and other holding locations (including a federal penitentiary). The majority of those confined in what the government euphemistically called “relocation centers” (see map below) were American-born citizens (Nisei). Others were Japanese nationals whom the law (prior to 1952) prevented from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. Worse still: over half the incarcerees were children. Wrongfully stripped of their rights and freedoms and incarcerated without due legal process, the overwhelming majority of those swept up by Roosevelt’s executive order and Public Proclamation No. 1, which established West Coast military exclusion area, would spend the next 2‑to‑5 years of their life in captivity behind barbed wire fences and armed guards.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (Public Law 100-383) had a long history leading up to it. Late in World War II (January 1945) and for months afterwards, the camps emptied themselves of their residents. The last to close—this on March 20, 1946—was Tule Lake Segregation Center, which held of all things “disloyal” incarcerees. Departing ex-incarcerees were given $25, ration coupons, and a 1‑way bus or train ticket and told to re-establish their lives as best they could wherever they could. Under the circumstances that was hard to do. Many adults had lost everything to their name: homes, deeds, cars, boats in the case of fishermen, farms and ranches, mom and pop stores, civil service jobs, savings accounts, etc. Often former incarcerees returned to communities where wartime prejudices and hostility against their race still lingered.

The process of redressing a national wrong was a long one, partially because Japanese Americans were of mixed mind. Some suffered pain and shame that, as a community, they had done something wrong to bring this constitutional violation upon themselves. When the discussion turned to monetary redress for their lost years of life and property, some saw that as a distraction from the main issue of egregious constitutional violations. Placing a price tag on violations of constitutional rights was downright insulting in their view. Finally, there was an argument that favored an official apology from the government as well as monetary compensation, even if the latter was largely symbolic. This last argument gathered support and resulted in the prestigious Japanese American Citizens League passing a resolution in 1978 demanding a presidential apology and monetary reparations.

Hawaii’s powerful Japanese American senator, Daniel Inouye, proposed what he saw as a sensible incremental approach to righting a national wrong; namely, creating a federal commission to research and investigate the wartime incarceration experience of those of Japanese heritage. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), authorized by the U.S. Congress in July 1980, received testimony from over 750 witnesses ranging from those who designed and implemented the war relocation camps to those who spent years in them.

The CWRIC issued its report, Personal Justice Denied, on February 24, 1983. The camps were wrong, it stated, the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” In separate Recommendations released in June that year, the commission called for a presidential apology and monetary redress payments of $20,000 (equivalent to over $54,000 in 2025) to each of the roughly 60,000 surviving Japanese Americans affected by Executive Order 9066. Five years of lobbying House and Senate members to ratify HR 442—the name of the bill evoked the memory of the U.S. Army’s Japanese American 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team—landed the bill on President Regan’s desk. His signature turned the bill into law. On October 9, 1990, in a ceremony in the nation’s capital, the first 9 of 82,219 redress payments were made.

Executive Order 9066 Cleared the Way for the Forced Exile and Relocation of West Coast Enemy Aliens and Japanese Americans to a New Existence in Confinement Camps Far From Their Homes

|

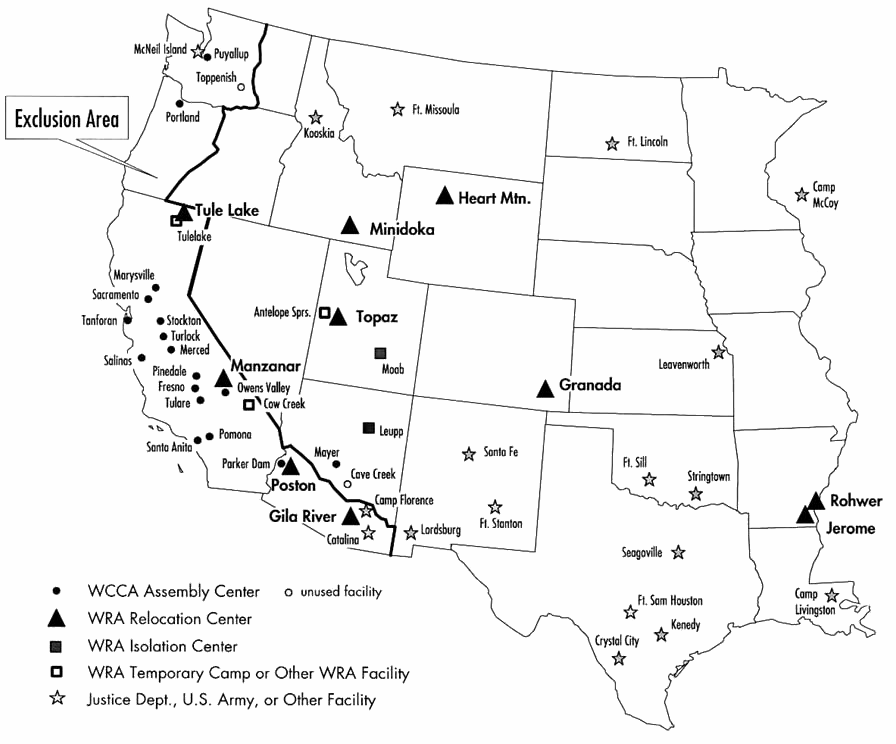

Above: Map showing (a) the massive West Coast World War II exclusion area (Military Areas 1 and 2) and (b) confinement camps in the continental U.S. for Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans as well as for over 31,000 suspected enemy aliens and their families confined under the Enemy Alien Control Program (Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526, and 2527). Ten hastily built “relocation centers,” as the War Relocation Authority’s confinement camps were euphemistically called at the time, are identified by black triangles. The 10 civilian-run confinement camps were built in 7 states all west of the Mississippi. All WRA camps were remote; many were situated in desolate deserts or swamps. U.S. Department of Justice-administered camps (there were 27) and U.S. Army camps (18) are represented by stars; for example, Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana and Fort Lincoln Internment Camp 5 miles/8 km south of Bismarck, North Dakota. It was to these often former Civilian Conservation Corps camps that people arrested in December 1941 and early 1942—that is, before Executive Order 9066 was in place—as well as thousands of German and Italian nationals living in the U.S. or deported from Central and South America were brought. In the map legend, WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration, WRA = War Relocation Authority. Purportedly for their own safety roughly 75,000 Japanese American citizens and 45,000 Japanese nationals living in the U.S., a number equivalent to the population of Santa Clara, California, would eventually be torn from their homes, neighborhoods, farms, fishing boats, and places of employment and worship in California (where the majority lived), Western Oregon and Washington, and Southern Arizona as part of the single-largest forced confinement in U.S. history. The Poston War Relocation Center on the Colorado Indian Reservation south of Parker, Arizona, was the largest such camp in America (peak population 17,814). Housing Japanese Americans mostly from Southern and Central California, Posten became the third-largest “city” in Arizona at the time. Together with the Rivers War Relocation Center on the Gila River Indian Reservation southeast of Phoenix, the 2 sites grew to hold 30,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them American citizens. In Hawaii, where 150,000-plus Japanese Americans comprised over one-third of the population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were removed to the mainland and incarcerated. On the Hawaiian island of Oahu, there were 17 incarceration sites, the largest and longest-operating being Honouliuli Incarceration Camp, which held 320 incarcerees and 4,000 prisoners of war. For their own “protection,” nearly 900 indigenous Aleuts were rounded up and confined in abandoned salmon canneries near Alaska’s capital Juneau, 2,000 miles/3,220 km from their island villages, which were burned to the ground as part of a “scorched earth” policy. On December 17, 1944, the Roosevelt administration rescinded Executive Order 9066, ending mass forced confinement and allowing ex-incarcerees to return to the West Coast exclusion area from where they came. Except for Tule Lake, the WRA camps would be emptied by the end of 1945.

|  |

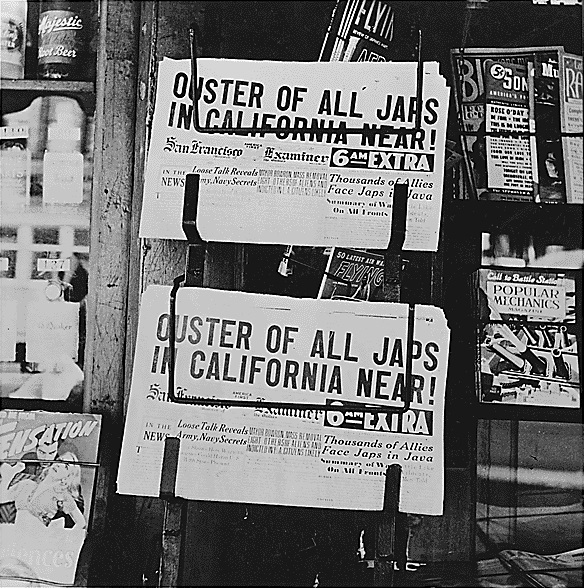

Left: “OUSTER OF ALL JAPS IN CALIFORNIA NEAR!” San Francisco Examiner headlines of Japanese roundup, forcible eviction, and “relocation” (government speak of the period) to inland military-run camps, February 27, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange. Lange was 1 of 3 photographers under contract with what became the War Relocation Authority in 1942–1943. The other 2 were Clement “Clem” Albers and Francis Stewart.

![]()

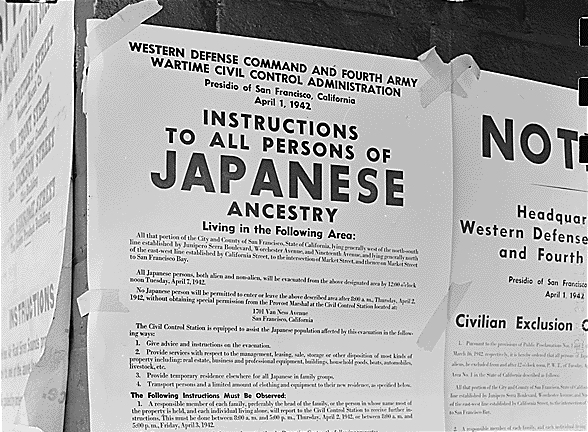

Right: Official notice of exclusion and forcible eviction, April 1, 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange. The posted exclusion order directed Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans living in the first San Francisco section to prepare to be exiled to remote government-run camps. Years before the December 7, 1941, Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the U.S. government had drafted plans to take into custody some Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans and had already placed some West Coast communities under surveillance for reasons of national security. This despite years’ worth of FBI and naval intelligence data that attested to residents of Japanese descent posing no threat of the kind.

|  |

Left: With luggage tags affixed to their clothing—an aid in keeping family units intact during all phases of their forced removal—members of the Moriji Mochida family await an “evacuation” bus in Hayward, Alameda County (San Francisco Bay area), California, May 8, 1942. On the luggage tags was written the family’s designated identification number. Mochida’s youngest child was 3. The Mochidas had operated a 2‑acre/0.8‑hectare nursery and 5 greenhouses in San Leandro, Alameda County, before their incarceration. Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

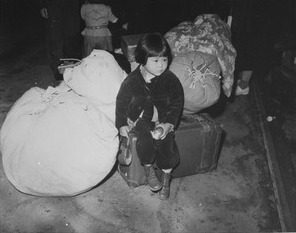

Right: Staring into uncertainty 2-year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa, clutching a tiny purse and an apple with a few bites gone, waits with the family’s allotment of baggage before leaving Union Station in Los Angeles, eventually arriving with her single mother at Manzanar War Relocation Center, more than 200 miles/322 km away in California’s Owens Valley, which would be her home for the next 3 years. Each family member was permitted to take bedding and linens (no mattresses), toilet articles, extra clothing, and “essential personal effects,” nothing more; in other words, only what could be carried. Photograph by Clem Albers.

|  |

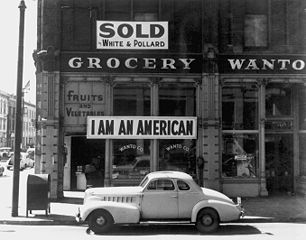

Left: This Oakland, California, store closed in March 1942 following orders to persons of Japanese descent to leave the U.S. West Coast (see map above). The owner, a University of California graduate, had ordered the “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign be suspended over his store shortly after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Declarations like these were insufficient to overcome the suspicion and contempt directed at people who looked like the enemy and who, it was widely assumed at the time, remained loyal to Japan and its Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa). Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

Right: In 1944 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders, described by many Americans as the worst official civil rights violation of modern U.S. history. After years of lawsuits and negotiations, on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally acknowledged that the wartime exclusion, forcible removal, and incarceration of Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans had been unreasonable. The act granted $20,000 tax free in reparations to each survivor of wartime incarceration (a little over 82,000 people), costing the U.S. Treasury $1.6 billion (equivalent to over $4.6 billion today). It took a decade to locate all eligible U.S. recipients and deliver them their checks and formal apology. In 1991 survivors of the more than 2,200 Latin Americans of Japanese descent who were evicted by their governments and incarcerated in U.S. camps were compensated with a pitifully small $5,000 check.

Injustice Camouflaged as Military Necessity: Japanese American Confinement During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click