PLANNERS MULL USING A-BOMB ON JAPAN

Pentagon, Washington, D.C. • May 31, 1945

On this date in 1945 a special group met in the Pentagon to search for an alternative to dropping the atomic bomb on Japan. The group had been called into existence by the new American president, Harry S. Truman. Neither Truman nor anyone else in the room knew what kind of damage the still-untested weapon might do.

What the planners thought they knew, however, especially as the ferocity of Japanese resistance on Okinawa became clear, was this: the tally of U.S. and Japanese war dead would boggle the mind. As it turned out, at the end of the Okinawa campaign (April 1 to June 21, 1945) the dead numbered 12,500 Americans and 110,000 Japanese; the loss in tanks, ships (36 sunk and 368 damaged), aircraft, and other materiel was so severe three-quarters of the way through the campaign that political and military leaders alike were increasingly wary of the endgame costs. The invasion of the Japanese main islands, or Home Islands, set to begin in November 1945 and end the next April, was predicted to cost as many as one million Allied lives, to say nothing of other losses on both sides. (Though the prediction came out after the war had ended, some analysts believed it was too low.)

Six weeks later, on July 16, a huge predawn explosion in the New Mexico desert settled the issue. “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world,” Truman wrote in his diary on July 25 while attending the victors’ Potsdam Conference outside the former Nazi capital of Berlin. Three days later, the Japanese cabinet under 77‑year-old Adm. Kantarō Suzuki, having failed to overcome the resistance of the overwhelming majority of Japanese military officers to the Allies’ final demand for their country’s unconditional surrender—the July 26 Potsdam Declaration—ignored the ultimatum, despite its explicit warning that the only alternative would be “prompt and utter destruction.” (The word used in the Japanese press for the cabinet’s non-response, mokusatsu, means “to kill it with silence” (as in silent contempt), though one Japanese-run newspaper, the Hong Kong News, broke press ranks to blast the Potsdam Declaration as a piece of unqualified impudence.) Days before, Truman had confided to Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, who was not officially a party to the Potsdam Declaration because his country had not yet declared war on Japan, that the U.S. was prepared to use its doomsday weapon “very soon unless Japan surrenders.”

But the president was concerned about where to use it. Neither Tokyo, or what was left of it, nor the ancient Japanese capital of Kyoto was an appropriate target for nuclear destruction. Truman ordered the Secretary of War to find targets with heavy concentrations of military personnel and to issue warning statements asking the Japanese to surrender to save lives. “I’m sure they will not do that,” he wrote in his private papers, “but we will have given them the chance.”

A short list of suitable targets was devised. Within 2 weeks Hiroshima and Nagasaki lay in ruins, not to be the last devastated Japanese city if the country didn’t surrender, Truman promised its leaders. The most destructive bomb in history killed 120,000 people (mostly civilians) outright, brought World War II to an end, and marked the beginning of the atomic age. Americans’ overwhelming desire to avoid further U.S. military casualties, combined with a desire for vengeance against Shōwa Emperor Hirohito, his warlords, and his subjects, left the majority of the country indifferent to killing on an atomic scale, at least initially.

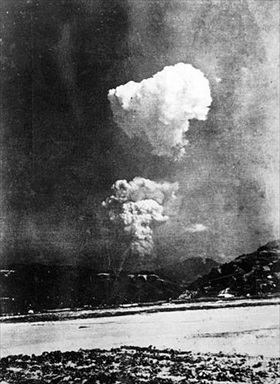

Hiroshima, August 1945

|  |

Left: U.S. Army poster prepares the American public for the invasion of Japan after ending war with Germany and Italy. President Truman’s military chief of staff, Army Gen. George Marshall, estimated that the U.S. armed forces would suffer up to one million casualties over the next two years trying to take the Japanese Home Islands by conventional force. Truman was unwilling to sell terms like these to the American public, in spite of likely becoming the object of condemnation in some quarters for ordering the atomic destruction of Japan.

![]()

Right: Mission map for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, August 6 (Enola Gay) and August 9, 1945 (Bockscar). Kokura, on the northern tip of the southern island of Kyūshū, appears on this map because it was the original target for August 9. Weather obscured visibility over Kokura, so Nagasaki, also on Kyūshū, was chosen instead.

|  |

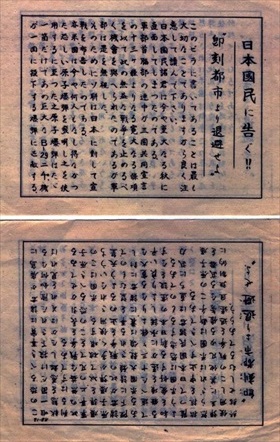

Left: Front and back of leaflets urging Japan’s quick surrender were dropped over the country by the 509th Composite Group, a group that comprised B‑29 bombers and transport aircraft. The 509th was a component of the U.S. Manhattan Project under the command of Lt. Col. Paul W. Tibbets, Jr. At 2:45 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay departed Tinian in the Mariana Islands for Hiroshima with Tibbets at the controls. Flight distance from Tinian to Hiroshima was just under 1,600 miles/2,575 kilometers, so it took the Enola Gay 6 hours to reach its destination. The atomic bomb, codenamed “Little Boy,” was dropped above the residential and commercial center of the city at 8:15 a.m. local time. (According to some historians the nonmilitary aspect of ground zero was intended to magnify the shock effect on the Japanese public and leadership in Tokyo.) Tibbets reported that Hiroshima was covered with a tall mushroom cloud after the bomb was dropped.

![]()

Right: Atomic cloud over Hiroshima, August 6, 1945, 8:45 a.m. This photograph was found in 2013 at Honkawa Elementary School (now a peace museum) and is believed to have been taken 6 miles/9.7 kilometers east of ground zero (aka hypocenter) about 30 minutes after detonation. Samples of beach sand 4 miles/6.4 kilometers and more from Hiroshima’s hypocenter reveal round, fine glassy shards that were once buildings and other urban-built structures that were swept up in the nuclear blast and fused in incredible heat before cooling and raining down to earth. Estimated to weigh in aggregate thousands of tons, these tiny spherical particles of the vanished city of Hiroshima, nicknamed “Hiroshimaites,” constitute up to 2.5 percent of the regular sand along the beaches of Hiroshima Bay.

|  |

Left: Hiroshima, the once-vibrant city of over a quarter million men, women, and children, September 1945. In the background the Genbaku (A-Bomb) Dome, the only structure left standing near ground zero. The building, at the time serving as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, later became a part of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

![]()

Right: Hiroshima, September 1945. Japanese officials determined that 69 percent of Hiroshima’s buildings were destroyed and another 6–7 percent were damaged. Out of some 70,000–80,000 people killed immediately in the blast and ensuing firestorm (a conservative figure), 20,000 were soldiers, a ratio of military to civilian dead President Truman had urged (the higher the better) in his directive to Secretary of War Henry L. Simpson. Needless to say the final tally of Hiroshima’s dead must include the tens of thousands who later succumbed to their horrific injuries and those who perished months and years later from radiation-related sicknesses.

Hiroshima: Dropping the Bomb, a BBC Production

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click