PACIFIC ALLIES LAUNCH CARTWHEEL

SWPA HQ, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia · April 26, 1943

By January 1943, as the six-month campaign for Guadalcanal in the Southwest Pacific Solomon Islands was winding down (the Japanese abandoned the island on February 7), it became clear that the Allies lacked sufficient resources to swiftly dislodge the Japanese from heavily fortified Rabaul, 650 miles to the west. Rabaul, sitting on the northern end of New Britain island, was Japan’s main forward operating base for naval and air units in the Southeastern Pacific, having fallen to an invasion force of 20,000 men the previous January. Rabaul’s huge bay—actually the caldera of a volcano—accommodated dozens of large warships and auxiliary vessels. Ashore, Japanese construction workers eventually excavated 350 miles of tunnels and caves into the volcanic soil around the town and installed underground barracks, clinics, maintenance facilities, and ammunition dumps.

In recognition of these developments the Allies announced on this date in 1943 a slower, more deliberate plan for Rabaul’s capture, codenamed Operation Cartwheel. It superseded a plan by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, who had proposed immediately after the Japanese naval defeat at Midway (June 1942) a quick campaign against Rabaul that would result in the capture of that bastion in less than three weeks (!). However, by the summer of 1943 the idea of “island hopping” past Rabaul was floated, gaining strength at the end of the year when American soldiers and Marines landed on the opposite side of New Britain from Rabaul, at Cape Gloucester, and found themselves tied down by disease and swamps as much as by the Japanese.

Eventually the Allies abandoned Rabaul as an objective. They cut off and bypassed Japanese strongholds to attack more lightly defended islands. The criterion became not how many Japanese troops and armaments they could defeat or destroy, but how to obtain islands to use as aerial launching pads en route north to Japan with the least risk of casualties. That said, seizing Japanese-held islands in a series of amphibious assaults was rendered costly by the fanatical determination of the Japanese defenders. In the Marines’ campaign to capture Tarawa Atoll in the Central Pacific Gilbert Islands (November 20–23, 1943), out of a modest-size garrison of 3,000 enemy troops, 1,000 construction workers, and 1,200 Korean forced laborers, just 17 Japanese (one officer and 16 enlisted men) and 129 Koreans survived the battle. Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the North, Central, and South Pacific theater areas, acknowledged the strategic importance of the U.S. victory at Tarawa. “The capture of Tarawa,” he stated, “knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific.”

Battle of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, November 20–23, 1943

|

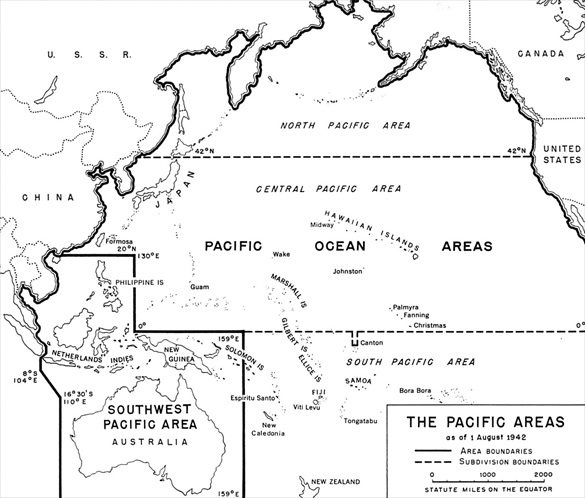

Above: Pacific Theater Command Areas, August 1942. Clockwise from top: Central Pacific and South Pacific (under Adm. Chester Nimitz), and Southwest Pacific (under Gen. Douglas MacArthur). Tarawa Atoll’s Betio Island—an island half the size of New York’s Central Park—and the Gilbert Islands straddle the dashed lines dividing the Central Pacific and South Pacific areas.

|  |

Left: Marines seek cover among their dead and wounded behind the sea wall on Red Beach 3, Tarawa, Gilbert Islands in the South Pacific, November 1943. The Battle of Tarawa was the first American offensive in this critical Pacific region, and it was also the first time in the war that the U.S. faced serious Japanese opposition to an amphibious landing.

![]()

Right: A Marine from 1st Marine Division uses a flamethrower to clear a path through what was once a thick jungle on Tarawa, 1943.

|  |

Left: Two Japanese Imperial Marines who committed suicide by shooting themselves rather than surrender to U.S. Marines, Tarawa, 1943. At Tarawa Americans faced one of the best, most concentrated Japanese defenses encountered in the Pacific War. The island’s 4,500 Japanese defenders were well supplied and well prepared, and they fought almost to the last man, exacting a heavy toll on U.S. Marines (1,009 killed and 2,101 wounded) and sailors (687 killed). Nearly all of the casualties occurred in the first 76 hours.

![]()

Right: Marines guard Japanese POWs dressed in rags on a Tarawa beach, November 1943.

With the Marines at Tarawa, U.S. Government Film (1944)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click