OPERATION OLYMPIC TO INITIATE JAPAN’S DOWNFALL

Washington, D.C. • May 25, 1945

On this date in 1945 the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, the primary national agency for the coordination and strategic direction of U.S. armed forces, provided President Harry S. Truman with a general outline of a plan to invade Japan, the last Axis nation still fighting World War II. Three days later Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), issued his strategic 2‑stage plan for an amphibious assault on Japan, codenamed Operation Downfall. The first stage, Operation Olympic, would be the invasion of Japan’s southernmost Home Island, Kyushu (Kyūshū), and the second stage, Operation Coronet, the invasion of Honshu (Honshū), Japan’s main island to the north of Kyushu. Tentative dates for Kyushu’s invasion—November 1, 1945; Honshu’s—March 1, 1946.

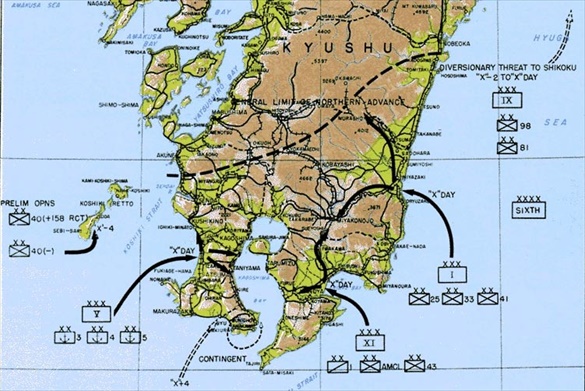

After U.S. forces had secured the Philippines (for the most part) and seized Okinawa in June 1945, the Japanese correctly deduced that the next American landings—these staged from Okinawa—would target Kyushu’s southern beaches (see map below). Augmented by men and equipment dispatched from the European to the Pacific theater, the U.S. and its allies could be expected to use Kyushu as a springboard for assaulting neighboring Honshu on which the Japanese capital, Tokyo, was located.

Approved by the Imperial High Command in March 1945, the Japanese scripted a secret plan to defeat the Allied assault on their homeland. Ketsu-Go was designed to engage the enemy’s invasion fleet as far from the Home Islands as possible using special attack aircraft (kamikaze), human-guided bombs, jet- and rocket-powered aerial bombs, and thousands of small suicide boats, midget submarines, and human torpedoes. Should the invaders manage to reach landfall, the script called for their annihilation on Kyushu’s beaches. Japan’s militarists, having been forced to surrender much of their territorial gains of the past few years, realized their country could not win the expansionist war they had started in the 1930s and ’40s. But by blunting, or best case turn back, the looming American assault on their homeland they hoped their nation could evade the enemies’ long-standing insistence on an unconditional surrender in exchange for a negotiated peace.

Given Japan’s late-war military weaknesses, that was doubtful. However, on paper Ketsu-Go appeared a reasonable defensive plan. (Ironically, only after Japan’s unconditional surrender on September 2, 1945, in Tokyo Bay did Gen. Walter Krueger’s Sixth U.S. Army G-2 (intelligence) officers learn of Ketsu-Go when they interrogated men of Japan’s Second General Army.) Troops of the Second General Army shouldered responsibility for defending the southernmost Home Island. Of the 14 divisions defending Kyushu when hostilities ended, two were divisions withdrawn from Chinese Manchuria that lacked combat experience. One division was transferred from Hokkaido in the north, and an army headquarters group moved from Formosa (today’s Taiwan) to Kyushu. Seven divisions were cobbled together from recent recruits and recalled reservists. U.S. G-2 additionally estimated that 140,000 recently mobilized civilian volunteers stood guard in Southern Kyushu and over 400,000 were deployed in the north. Tragically for the defenders, numbers mattered little because half of Kyushu’s 917,000 defenders lacked rifles and bayonets, and mortars had replaced field artillery.

Still, Kyushu defenders played their assigned roles, ready or not. Fortunately for both combatant nations—Japan and the U.S.—hostilities ceased on August 17, 1945, hours after Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) broadcast his capitulation speech to the world. Kyushu was spared an American invasion though not American wrath. On August 9 Nagasaki, the large industrial city of 195,000 people in Kyushu’s north, was laid to nuclear waste. Dead (39,000) and injured (25,000), mostly civilians as awful as that was, never approached the Sixth U.S. Army’s chilling estimate of 394,859 U.S. casualties had Operation Olympic lasted 120 days.

Defending the Japanese Homeland Against the Planned U.S. Invasion, 1945–1946

|

Above: Operation Olympic was to have been launched on November 1, 1945, from an Allied naval armada that would have been the largest ever assembled, surpassing the Overlord (D-Day) invasion of Normandy, France, in June 1944. It was to have included 42 aircraft carriers, 24 battleships, and 400 destroyers and destroyer escorts, and hundreds of troop transports. Fourteen U.S. divisions and a “division-equivalent” (2 regimental combat teams) were scheduled to take part in the initial landings, 3 more divisions than Overlord had. Tactical air support for Olympic (renamed Majestic when that codename appeared compromised) was to have been the responsibility of 3 U.S. Army Air Forces (the U.S. 5th, 7th, and 13th AAF), which were to win and maintain air superiority over 35 landing beaches named after automobile brands at 3 points in the southern third of Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s 4 Home Islands. The points were Miyazaki, Ariake, and Kushikino identified on the map by arrowheads and the words “X” DAY. U.S. planners estimated that their 3 corps (l-r V, XI, and I), 1 corps assigned to each landing point, would outnumber the Japanese by approximately 3 to 1. The conquest of Southern Kyushu was to offer a staging ground and a valuable airbase for Operation Coronet and the climactic Battle for Tokyo tentatively set to kick off on March 1, 1946.

|  |

Left: Female students receive training in gun handling as members of a volunteer fighting corps, or Kokumin Giyū Sentōtai, in Tokorozawa, now considered a suburb of Tokyo. Governors of prefectures (states) could conscript all male civilians between the ages of 15 and 60 years, and unmarried females between 17 and 40. Commanders were appointed from retired military personnel and civilians with weapons experience. The Kokumin Giyū Sentōtai was intended as the main reserve, along with a “second defense line,” for Japanese forces to sustain a war of attrition against invading forces. After the Allied invasion, these forces were intended to form resistance or guerrilla warfare cells in cities, towns, and mountains. At this stage of the war, most militia members were armed with swords, sickles, knives, fire hooks, and even bamboo spears due to the lack of modern weaponry and ammunition.

![]()

Right: Student militia at Kujukurihama, Chiba, a prefecture situated east of Tokyo across Tokyo Bay. Some 28 million men and women were considered “combat capable” by the end of June 1945; yet only about 2 million were recruited when the war ended, and most of these never experienced combat owing to Japan’s surrender before the Allied invasion of the Japanese home islands could proceed.

|  |

Left: In this photo an officer of the Japanese Army instructs a group of housewives in the use of bamboo spears. Everyone was enlisted in the defense of the Japanese homeland.

![]()

Right: Rifles slung over their shoulders and bayonets lashed to their belts, Buddhist monks march in step under the watchful eye of a Japanese soldier. This drill took place on the grounds of their Buddhist temple.

Newsreel Documenting Japan’s Unconditional Surrender on Board the USS Missouri, September 2, 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click