HUSKY, OPERATION (ITALIAN CAMPAIGN, 1943)

| When | July 9/10 to August 17, 1943 |

| Where | The Italian island of Sicily

|

| Who | Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s (1885–1945) U.S. Seventh Army and Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery’s (1887–1976) British Eighth Army (which included the First Canadian Infantry Division) under the overall command of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Expeditionary Force. British General Sir Harold Alexander (1891–1969) acted as Eisenhower’s second in command. An armada of nearly 2,600 ships in two naval task forces, one British, one American, transported and supported the invading armies. Arrayed against the Allies were two corps of the Italian Sixth Army under Gen. Alfredo Guzzoni (1877–1965), the woefully unfit commander of Axis troops on the island until August 2, when German Gen. Hans-Valentin Hube (1890–1944) assumed control of the Sicilian front. |

| What | The invasion of Sicily was the largest amphibious assault up to that time. Airborne units supported both Allied armies. Initial Allied strength was 180,000 personnel, 600 tanks, and 1,800 guns. Facing the Allies were 230,000 Italians and 60,000 Germans (whose numbers were increased by reinforcements from the mainland), 260 tanks, and 1,400 aircraft. In the fighting the Allies suffered 23,934 casualties, while Axis forces incurred 29,000 casualties and 140,000 captured. Italian soldiers surrendered, as one American put it, “in a mood of fiesta.” Three Germans surrendered to a lone American, saying they had been fighting three years and eight months and “we’re sick of it all.” |

| Why | With the end in sight of the North African Campaign (which included Operation Torch), Allied political and military leaders meeting in Casablanca, Morocco, in January 1943 favored an invasion of Italian Sicily or Sardinia, arguing that it would force Germany to dispatch military units away from the Eastern Front to a new Southern Front, perhaps knock Italy out of the war, and might move Turkey to join the Allies. A corollary objective was to open the Mediterranean to Allied shipping by removing Axis air and naval forces from the island. |

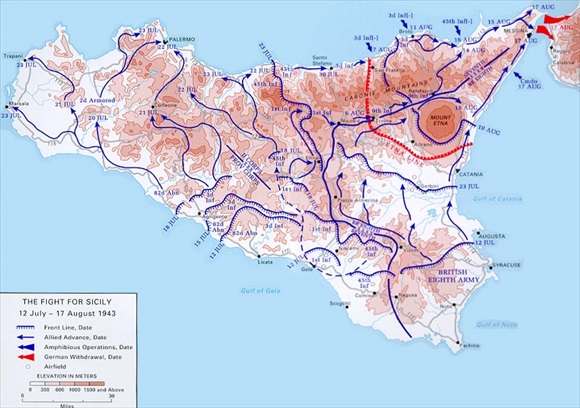

| Outcome | Operation Husky was the start of the Italian Campaign in Southern Italy (September 3 to December 15, 1943) and went off with surprisingly few hitches. Landing on the south of the island, Patton’s Seventh Army reached Palermo, the island’s capital on the northern coast, on July 22. Montgomery’s Eighth Army made slower progress due to more difficult terrain and stiff German resistance. As reinforcements poured in, Allied forces eventually totaled 400,000. Only after Italian dictator Benito Mussolini fell from power on July 25, 1943—spurred by the loss of Palermo, where Patton’s soldiers were greeted as liberators three days before—did Hitler order an evacuation of the island. Hube, the commander of the German forces, used air and naval support to keep the Messina Strait escape route open until the last of his troops crossed to the Italian mainland during the night of August 11/12. Roughly 100,000 Italian soldiers also escaped, though they left 150,000 of their comrades in arms in Allied captivity. (The number of Italian prisoners taken during Operation Husky is on top of the 250,000–350,000 Italians captured during the North African Campaign.) The next step for the Allies was an assault of the mainland, which began on September 9, 1943, with Montgomery’s Eighth Army landing on the toe and heel of the peninsula and Patton’s Seventh Army landing further up the boot at Salerno. The successful amphibious and aerial campaign on Sicily taught the Allies valuable lessons that were utilized the following year at Normandy (Operation Overlord). |

![]()

Operation Husky: The Allied Invasion of Sicily, July–August, 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click