ONSET OF RUSSIAN WINTER BODES ILL FOR HITLER

Moscow, Soviet Union · October 15, 1941

On June 22, 1941, the day Adolf Hitler sprang his surprise attack on the Soviet Union, he reportedly confided to some of his intimates: “I feel as if I have opened a door into a dark, unseen room—without knowing what lies behind the door.” His gloomy premonitions soon gave way to glee as intoxicating reports of military victories came across the news wires. Advancing German armies occupied vast stretches of the Baltic States, Belarus, and the Ukraine. At a press briefing in Berlin on October 10, 1941, Hitler’s press chief, following a meeting with his boss the day before on the Eastern Front, released the first substantial news about Operation Barbarossa. The very last remnants of the Red Army, Otto Dietrich told journalists, were locked in two German steel pockets before Moscow, the Soviet capital, and were undergoing swift, merciless annihilation.

The German conquest of Russia would allegedly add more manpower at Germany’s disposal than all the manpower available to England, North America, and South America combined—a very disturbing development were it to be realized. Ominously, however, for the war planners at Hitler’s remote dream world, “Wolf’s Lair” (Wolfsschanze) in Rastenburg, East Prussia (today’s Polish village of Kętrzyn), where the Fuehrer was busy directing military operations far from the front, the first heavy snowfalls of the Russian winter were recorded on this date, October 15, 1941. Four days later Soviet officials declared their capital to be in a “state of siege.”

The Battle of Moscow (October 1941 to early January 1942; the Germans named it “Operation Typhoon”) was intensified as Red Army forces from the Soviet Far East and Siberia began arriving on the Russian Front. On December 2 a single German battalion snow-shoveled close enough to Moscow to glimpse the golden spires of the Kremlin. But that was as near as any Wehrmacht ground unit got before withdrawing behind German lines, where fuel froze, machine guns ceased firing, and ill-clad soldiers died from severe frostbite. (Temperatures reached 36°F below zero.) Hitler’s vague hope that Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin would come to realize the hopelessness of further resistance, would abandon European Russia to Germany, and would content himself with a country east of the Ural Mountains was swept away by frigid typhoon-force winds now blowing in his face.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1612001203,0307275337,0374139784,1612002188,1781590702,1107035120,0312628196,0691140421,0811711250,0752426923″ /]

German Invasion of the Soviet Union Stopped Cold by 1941 Russian Winter

|

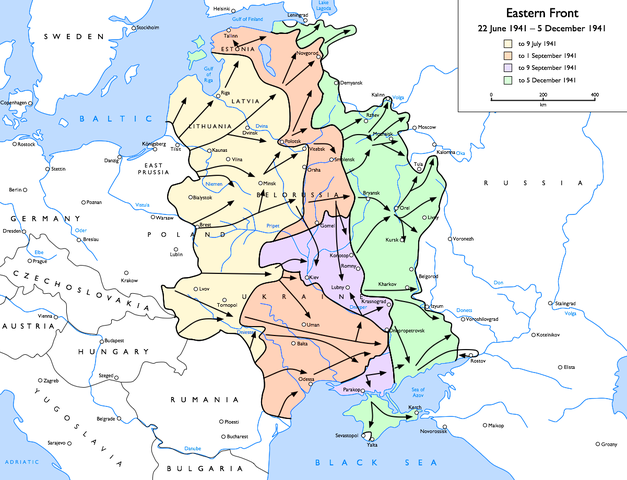

Above: Map of German operations against the Soviet Union, June 22 to December 5, 1941. Operation Barbarossa was the largest military operation in history in both manpower and casualties.

|  |

Left: Armed with heavy shovels, a hastily assembled work force of Moscow women, teenagers, and elderly men gouge a huge tank moat out of the earth to halt German panzers (armored units) advancing on the Soviet Union’s capital and largest city. In the feverish effort to save the city, some 250,000 citizens labored from mid-October until late November digging ditches and building other obstructions. When completed, the ditches extended more than 100 miles.

![]()

Right: Muscovites installed antitank barricades on city streets in October 1941. Between October and the end of November, the capital remained within reach of German panzers, which never came. Moscow was, however, the object of massive air raids, though these caused only limited damage because of extensive antiaircraft defenses and effective civilian fire brigades.

|  |

Left: German soldiers pull a staff car through heavy mud on a Russian road, November 1941. Hitler, arrogant and ruinously overconfident owing to his blitz of successes in Western Europe, expected a victory in the East within a few months, and therefore he did not prepare his Wehrmacht (armed forces) for a campaign that might last into a wet late fall, much less a bitterly cold winter. The assumption that the Soviet Union would quickly capitulate—Hitler had promised his generals that a single campaign would crush “the rotten edifice of bolshevism”—proved to be his, as well as the Wehrmacht’s, tragic undoing.

![]()

Right: On December 2, 1941, the first blizzards of the Russian winter began just as one unit of the Wehrmacht caught a glimpse of the spires of Moscow’s Kremlin 15 miles away. That same day a reconnaissance battalion crept to within 5 miles of Moscow, but that was as close to the military prize as any Wehrmacht unit managed. In this photo a Panzer IV tank in white camouflage is stranded in deep Russian snow as its crew attempts to free it. At the right edge of the photo is a war correspondent who filmed the scene for audiences back in Germany.

|  |

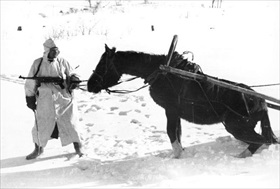

Left: A German soldier with machine-pistol and white winter coat tugs at a horse pulling a cart in snow-covered landscape west of Moscow. Horse-drawn supply transports as well as combat units were equally stopped first by autumn mud, then by deep winter snow. Heinz Guderian, commander of the German Second Panzer Army, wrote in his journal: “The offensive on Moscow failed. . . . We underestimated the enemy’s strength, as well as his size and climate. Fortunately, I stopped my troops on 5 December, otherwise the catastrophe would be unavoidable.” For his efforts Guderian was relieved, along with 40 other generals, of his command on December 26, 1941.

![]()

Right: Two German soldiers in heavy snow on guard duty west of Moscow, December 1941. December’s low temperature reached -20°F. More than 130,000 cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers. The unforgiving weather hit Soviet troops, too, but they were better prepared for the deadly cold.

Following Initial Successes, Hitler’s Wehrmacht Prepares to Advance on Moscow

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click