NUREMBERG DEALT AERIAL KNOCKOUT BLOW

London, England • January 2, 1945

In the 19th century the Bavarian city of Nuremberg, long associated with gingerbread, sausages, handmade toys, and Christkindlmaerkte (Christmas markets), had become an important industrial center with companies such as engineering and manufacturing giants Siemens and MAN. Both firms contributed mightily to Germany’s war effort—Siemens by producing everything from communications equipment to electrical and mechanical components for U‑boats, aircraft, and V‑1 and V‑2 rockets. Nuremberg’s MAN produced 40 percent of all Panther medium tanks built by Nazi Germany. MAN also supplied diesel engines for submarines and artillery of every description. Altogether, the city was home to over 120 armament firms.The Royal Air Force Bomber Command had long had Nuremberg in its bombsights. On August 10, 1943, the RAF dropped 1,500 tons of bombs on the city and another 1,500 tons on August 27, leaving over 4,000 dead at a cost of 49 Allied bombers. The next year, on the moonlit night of March 30/31, 1944, Bomber Command dispatched an armada of 795 aircraft, which German radar picked up at the Belgian border. Nearly 12 percent of Bomber Command’s air fleet was lost during the raid, shot down or crash landed on its way back to home bases; more than 700 crewmen went missing, as many as 545 of them dead, more in that 1 night than during the entire Battle of Britain. More than 160 airmen became prisoners of war. It was the heaviest loss in men and equipment in the entire Allied strategic bombing campaign of Germany, with little to show for it.

While few of Nuremberg’s military targets were damaged in air campaigns in 1943 and 1944, the Anglo-American air forces resorted to increasing attacks on the city’s residential areas starting in 1945. On this date, January 2, 1945, Nuremberg’s medieval Altstadt (old town) was systematically destroyed by 521 RAF bombers. Over 6,000 “blockbuster” high-explosive bombs and over a million firebombs were dropped on the heart of the city. Roughly 90 percent of the city’s center (29,500 homes) was reduced to ashes, killing 1,800 residents, wounding 5,000, and displacing some 100,000. Not included in the casualty toll were Soviet POWs, who were located in camps between the railway classification (marshalling) yard and the MAN factory. Allied “terror fliers,” as the Germans called them, returned the next month in the form of 2,396 U.S. B‑17s and B‑24s. Because cloud cover over Nuremberg on February 20 and 21, 1945, prevented precision bombing of military targets, the bombardiers dropped their payloads willy-nilly over the whole of the city, killing over 1,300 more residents and rendering another 70,000 homeless.

Nuremberg, January 2, 1945: Near-Perfect Example of Saturation Bombing

|  |

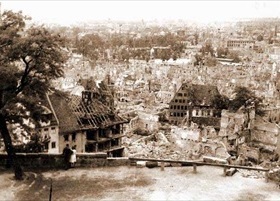

Left: Nuremberg, scene of so many disappointments for RAF Bomber Command in 1943 and 1944, finally succumbed on January 2, 1945. The center of the city, particularly the eastern half, was destroyed. The historic imperial fortress (Kaiserburg), the Rathaus (city hall), almost all the churches (including 3 centuries-old Gothic churches, St. Lorenz, St. Mary’s [Frauenkirche], and St. Sebaldus), and about 2,000 preserved medieval houses went up in flames. Photo looking north from Nuremberg center toward the Kaiserburg. Helga Lades, a teenage survivor of 1 night’s bombing, emerged from her family’s apartment cellar to find a direct hit had cut their home in two. The city’s silhouette “was charred and jagged from gaping wounds the bombs had repeatedly inflicted. . . . People wandered the streets trying to collect themselves, family members, and whatever measures of provision they could find. It was chaotic. Children cried. Women cried. Men cried. Grief fell on the city like a weighty cloak that could not be shaken off.” Quoted in Helga Lades Allison with Kathleen Jones, Because of Whose I Am: A Nazi’s Daughter, p. 72.

![]()

Right: The area of destruction also extended into the more modern northeastern and southern city areas. The industrial area in the south, containing the important Siemens and MAN factories, and the railway areas (shown here) were also severely damaged. Over four hundred separate industrial buildings were destroyed.

|  |

Left: Nuremberg in the summer of 1945. In the distance is St. Mary’s Church (Frauenkirche). Behind the destroyed buildings is the Hauptmarkt, the main market. Nuremberg, particularly its Altstadt, had a large proportion of half-timbered houses with high wood content, making the buildings highly combustible and attractive to an air attack by Allied bombers using a combination of high explosives and incendiary bombs.

![]()

Right: View of Nuremberg bomb damage from the Castle Hill (Kaiserburg). After Cologne, Dortmund, and Kassel, Nuremberg had the largest amount of rubble per capita: half of all residences in the city were destroyed and those that remained for the population of 195,000 (half its prewar population) were mostly damaged. Despite this intense degree of destruction, the city was rebuilt after the war and was to some extent restored to its prewar appearance, including the reconstruction of some of its medieval buildings. However, the biggest part of the historic old imperial city was lost forever.

Nuremberg Then (1945) and Now (2017)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click