NORWEGIAN COMMANDOS HALT HEAVY WATER PRODUCTION

Vemork/Rjukan, German-Occupied Norway • February 27, 1943

Following Germany’s invasion of Norway in April 1940, German authorities took control of Norsk Hydro’s Vemork hydroelectrical and chemical facility just outside Rjukan in Telemark County. Vemork lay 100 miles/161 km west of Oslo, Norway’s capital. Although originally designed to zap descending mountain water with an electric current (electrolysis) to produce ammonia for nitrogen fertilizer, Vemork had recently become the world’s first industrial-scale production site of “heavy water,” or deuterium oxide (D2O). (Heavy water refers to water containing a large proportion of deuterium oxide compared with ordinary water.) The plant was set up to produce many hundreds of kilograms of heavy water per year. Indeed, by May 1942 Vemork was producing 286 lb./130 kg of heavy water a month. German scientists, unlike their American contemporaries who were also involved in nuclear weapons research, had decided to use heavy water as a “moderator” in their nuclear reactor, not the more readily available graphite with which the Americans were experimenting. (A moderator slows down the bombardment of neutrons and the fission process [i.e., the splitting of atoms], which releases huge amounts of energy.)

Now none of this physics talk ever reached the ears of the 9 Norwegian commandos who infiltrated the Vemork plant on this date, the evening of February 27, 1943. They were neither told by their British SOE (Special Operations Executive) handlers what the Germans intended to do with all the thousands of kilograms of heavy water they suddenly needed nor told what effect their covert operation, if successful, might have on the outcome of the war. What the commandos knew for certain was that Operation Gunnerside, their planned sabotage of the critical water cells in the plant basement where the heavy water was manufactured, followed on the heels of two earlier SOE-sponsored covert operations. A reconnaissance team of four Norse soldiers (Operation Grouse/Swallow, October–November 1942) was airdropped to prepare the way for an attack on the plant by a party of 30 British commandos, whose military gliders crash-landed miles short of their targeted landing site (Operation Freshman, November 19, 1942). Twenty-three men who survived the crashes were tortured and killed by the Gestapo (German Secret State Police).

Given the urgency to put the Freshman fiasco in the past, the British dropped 6 Gunnerside parachutists into Norway on February 17, 1943. Meticulous planning, additional details of the plant layout, and good luck were the reasons given by the Gunnerside commandos for the success of their covert mission. Ten days after insertion, now reinforced by 3 Swallow scouts, a 9‑member sabotage squad led by Lt. Joachim Rønneberg reached the Vemork plant without being detected by German and Norwegian guards. Four men from the 5‑man demolition squad, also directed by Rønneberg, daisy-changed detonator cords and charges next to the delicate basement machinery and lit the 30‑second fuses before making a clean getaway. The pyrotechnics were lethal: all 18 4‑ft‑tall/1.2‑m‑tall ultrafiltration cells were blown apart, their contents, mixed with the plant’s overhead cooling water, running into floor drains. Seeking revenge, 12,000 enemy troops swept the Vemork area, to no avail. After skiing more than 200 miles/322 km, the Gunnerside crew reached safety in neutral Sweden, then England, where they were joined by the Swallow quartet.

The Gunnerside raid cost the Germans 350 kg/770 lb. of pure heavy water. The plant was decommissioned for a few months. But the spectacular success of the covert operation was trumped by one of the Gunnerside’s own raiders, Knut Haulelid. Instead of returning to England, the Brooklyn native recruited a team of Norwegian saboteurs to sink a ferry 1 week short of Gunnerside’s first anniversary. Nineteen pounds/8.6 kg of plastic explosive secreted in the bow of the SF Hydro, which was carrying semi-finished heavy water from the Vemork plant to research centers in Germany, delivered the last barrels of the precious stuff to the bottom of Lake Tinn (see photo essay below).

Norwegian Commandos Sabotage Germany’s Atomic Weapons Program

|  |

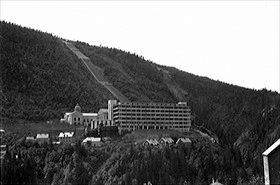

Left: Norsk Hydro’s Vemork hydroelectric plant near Rjukan, Norway, in 1935. At Rjukan a large waterfall was harnessed to produce chemicals related to the production of artificial fertilizer, including ammonia, potassium nitrate, heavy water (deuterium oxide), and hydrogen. In 1925 the plant partnered with Germany’s IG Farben and later with Britain’s Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). Starting in December 1934, the Vemork plant was the only facility in Europe that mass-produced high concentrations of heavy water (a byproduct of nitrogen fixing) in the 8‑story granite electrolysis building shown in the foreground of this photograph. The heavy-water plant was closed in 1971. Today the original power plant is an industrial museum. One of its exhibitions covers the 5 sabotage operations conducted by the Norwegian resistance movement, British commandos, and U.S. bombers between 1942 and 1944 to destroy the plant’s capacity to aid the Nazis’ atomic bomb program, which depended on extremely scarce heavy water as a “moderator” in achieving a successful nuclear chain reaction. The Norwegian Broadcasting Company produced a 6‑part miniseries, Kampen om tungtvannet (The Heavy Water War), about the SOE-trained saboteurs. The miniseries broke the record for the most highly viewed television drama in Norway. A 5‑minute trailer with English subtitles can be viewed on YouTube by clicking here.

![]()

Right: The twin-stack steam-powered railway ferry SF Hydro operated on Lake Tinn (Tinnsjå, Tinnsjø). The 19‑mile‑/30.5 km‑long ferry trip made it possible for Norsk Hydro to transport its chemicals from the Vemork plant at Rjukan to the coastal port at Skien. On February 20, 1944, the ferry was blown up by the Norwegian resistance movement at Lake Tinn’s deepest point (1,411 ft/430 m) with a load of semi-finished heavy water onboard, which was headed to Nazi Germany for what appeared to be a last-gasp use in that country’s nuclear weapons program. (The Nazis had decided to abandon Vemork, their only source of heavy water, after the U.S. bombing of the facility on November 16, 1943.) The Lake Tinn bookend to Operation Gunnerside deprived Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich of any chance, if there ever was one, of producing an atomic bomb. After the war it was confirmed that the Germans were not even close to making an atomic bomb as the Allies had feared throughout the European conflict. In his memoirs Nazi Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer wrote: “On the suggestion of nuclear physicists we scuttled the project to develop an atom bomb by the autumn of 1942” because, as he said elsewhere, “the technical prerequisites for production would take years to develop.” German wartime resources were thus allocated to other priorities; e.g., V‑2 ballistic rocket and jet aircraft research, development, and manufacturing. The wreck of the ferry and its invaluable contents were discovered in 1993. Sadly, the sinking of the SF Hydro resulted in 4 German and 14 Norwegian casualties. A largely fictional Hollywood account of the sabotage, The Heroes of Telemark (1965), starred Richard Harris as Knut Haukelid, second in command of Operation Gunnerside. The film is probably the best-known cinematic representation of one of the most heroic sabotage acts of World War II.

History of Norway-Based Efforts to Sabotage German Nuclear Weapons Program

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click