NORWAY’S QUISLING MEETS HITLER

Berlin, Germany · December 14, 1939

On this date in 1939 Adolf Hitler and high-ranking members of the German navy and army met with Norway’s Vidkun Quisling, whose private visit to Berlin had been sponsored by Alfred Rosenberg, the Nazi Party’s chief racial theorist. From 1931 to 1933 Quisling had served as Norway’s minister of defense. Following his cabinet service, he founded a small pro-German, anti-Semitic, anti-British, and anti-Soviet political party called the Nasjonal Samling (National Unity). Rosenberg and Quisling’s fascist party maintained regular contact. Three days prior to meeting Hitler, Quisling and his entourage had informed Kriegsmarine Grand Admiral Erich Raeder that they wanted to place Norwegian military bases at Germany’s disposal in order to prevent Britain from gaining a foothold in Norway. The two meetings had enormous consequences for Norway when Hitler straightaway ordered his armed forces to investigate how Germany could occupy that country after Raeder had pointed out that Great Britain, at war with Germany for the last three months (since September 3, 1939), received substantial supplies that passed through Norway: denial of British access to these valuable raw materials (chiefly iron ore) and foodstuffs would surely shorten the war, so it was alleged. Ironically, just as the wheels in Berlin were set in motion, the British War Cabinet on December 22, 1939, directed its military staff to also draw up contingency plans for operations in Norway. The plans were presented to the War Cabinet the day after New Year’s, 1940. The Allied Supreme War Council was briefed on the plans on February 5, a little more than two months before Quisling welcomed German boots on his country’s soil. On April 9, 1940, the day Germany invaded Norway, Quisling took to the airwaves to pronounce himself head of a new national government. He ordered all resistance to end (it did not) and threatened to take action against those who did not obey. Quisling remained “head of government” for six days until Hitler dumped him in an effort to quell resistance to the invasion. Eventually German occupation authorities found they had a need for Quisling, and for his treachery he remained at the helm of a collaborationist government until the country was liberated five years to the day after Norway’s capital succumbed to German troops.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1935149334,0521041155,162873664X,8251801648,1484032446,1846031176,1591143233,159114051X,0803277873,1848326610″ /]

Norway Under German Occupation, 1940–1945

|  |

Left: Nazi Party chief racial theorist Alfred Rosenberg was one of Vidkun Quisling’s most important allies in Berlin. After his December 1939 meeting with Quisling, Rosenberg wrote in his diary that the next time the two men met, “Norway’s minister president will be named Quisling.” Quisling became increasingly anti-Semitic during the course of the war. In Frankfurt in 1941 he spoke to Rosenberg’s “Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question,” which was dedicated to identifying and attacking Jewish influence in German culture. One of Quisling’s first acts when he became minister president in 1942 was to reintroduce the prohibition of Jews entering Norway, which was formerly a part of the Constitution from 1814 to 1851. Norwegian police in many cases helped the German occupiers apprehend Jews. In 1946 there were only 559 Jews living in Norway.

![]()

Right: German soldiers marching down Oslo’s main boulevard, Karl Johans gate, April 9, 1940, the day of the German invasion. In the background is the Norwegian Royal Palace, which later became Quisling’s residence after King Haakon VII and his family escaped to England and established a government in exile. Quisling and his fascist political party, Nasjonal Samling (NS, literally “National Unity”), had little effect on German operational planning for the invasion of Norway. The Germans used the Nasjonal Samling as a source of information on political conditions in the country, but Quisling was not informed about the forthcoming attack and his organization had no part in German military operations in Norway.

|  |

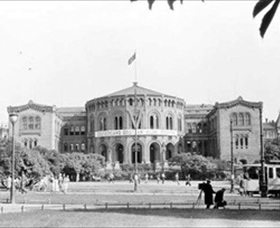

Left: Quisling’s short-lived April 1940 government took up residence in Norway’s parliament building (Stortinget), shown here flying the swastika. It lasted only six days before it was set aside by the Germans and eventually replaced by an 11‑man council of Nasjonal Samling members headed by Quisling. On February 20, 1942, Quisling was installed as head of state, assuming the powers of king and parliament. He remained in that post until Norway was liberated in April 1945. The white banner on the front of the parliament building reads, “Germany Is Victorious on All Fronts.”

![]()

Right: Quisling was pleased to provide his autograph for this admirer in 1943. Among most Norwegians the Quisling regime had next to no support, partly because of Quisling’s coup attempt on April 9, 1940, and partly because his collaborationist government was in conflict with Norway’s constitution and political traditions. After the war Norwegians insisted on settling accounts with all 40,000 “Quislings.” (The word “Quisling” had entered the English language in April 1940 as a synonym for “traitor.”) A Norwegian court convicted the former head of state of treason, murder, and theft and ordered his execution by firing squad in Oslo’s Akershus Fortress on October 24, 1945.

|  |

Left: On February 13, 1942, Hitler received Quisling in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. Quisling, one week away from being installed as Norway’s minister president, is shown in the company of civilian Reichskommissar for Norway Josef Terboven (to his rear), who was the real power in Norway. Mostly ignoring Quisling’s collaborationist government, Terboven established a regime of terror in Norway, personally commanding a force of roughly 6,000 goons, of whom 800 were part of the secret police. Terboven’s men operated outside the 400,000 regular German armed forces stationed in Norway. On May 8, 1945, the day of Germany’s capitulation, Terboven and the commander of the Norwegian SS committed suicide, Terboven by blowing himself up in a bunker at his official residence.

![]()

Right: Quisling and Terboven are seen inspecting a detachment of Hirden, the ideological and paramilitary organization of Quisling’s Nasjonal Samling. (“Hirden,” from old Norse, referred to a bodyguard in service to Norwegian and Danish kings and lords.) The Hirden were equivalent to Hitler’s Sturmabteilung, or SA. Membership in the Hirden was mandatory for all NS members in the course of the war. Estimates of their numbers range from 8,500 to 20,000.

Vidkun Quisling: Nazi Collaborator, Part 1

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click