NISEI ENROLLED IN U.S. ARMY’S JAPANESE LANGUAGE SCHOOL (MISLS)

Camp Savage, Minnesota • June 1, 1942

On this date in 1942 Japanese linguistic classes began at the U.S. Army’s Camp Savage, 15 miles from Minneapolis, Minnesota, for 200 enlisted men, of whom 193 were Nisei (second-generation U.S. offspring of Japanese immigrants) and the remainder Caucasian. Camp Savage’s 6-month curriculum trained Japanese-speaking soldiers in gathering, translating, analyzing, interpreting, and forwarding intelligence from sources deemed to have credible tactical importance; e.g., captured Japanese military documents, enemy soldiers and civilians, radio intercepts, diaries, and correspondence. Graduates of the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) were attached to combat and noncombat units of the United States Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, as well as to similar units in the British, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, Chinese, and Indian services.

Recruitment of primarily Nisei volunteers for MISLS began one month before Japan’s sneak attack on American and British territorial and military interests on December 7 and 8, 1941, which triggered World War II in the Pacific. Owing to the large number of ethnic Japanese living in the continental U.S. (127,000, mostly on the West Coast) and Hawaii (158,000), the first set of 60 MIS linguists were trained and housed at San Francisco’s Presidio, where 45 students graduated in May 1942. These MISLS students were among the roughly 5,000 Nisei already serving in the U.S. Army. Then came Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which forcibly removed Japanese nationals, their U.S.-born children, and Japanese American soldiers from the U.S. West Coast without due process and, with respect to the U.S.-born, in violation of their birthright under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The order prompted the language school to relocate to the welcoming state of Minnesota, home to all of 51 people of Japanese descent. In 1944 the school outgrew Camp Savage and moved to nearby Fort Snelling. There the language school continued to grow, occupying 120 classrooms staffed by more than 60 instructors. Over 6,000 GIs passed through the MISLS program by the time it shut down. At its peak in 1946 the school had 160 instructors, 3,000 students, and a June graduating class of 307. By then MIS linguists had translated 20.5 million pages, 18,000 enemy documents, created 16,000 propaganda leaflets, and interrogated over 10,000 Japanese POWs.

The Presidio’s May 1942 graduates were immediately deployed to front lines in Asia Pacific combat zones: Alaska, Australia, South and Central Pacific, Southeast Asia, and China. Following the naval Battle of Midway (June 4–7, 1942), MIS linguists were committed to every major engagement against Japanese forces until Japan’s surrender on September 2, 1945. Two examples: three Japanese-language teams in different parts of the world provided information that led to the ambush and death of Japanese Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto’s aircraft over Bougainville Island on April 18, 1943. In March–June 1944 Nisei linguists stationed in Australia provided the key to the lopsided U.S. victory in the Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944).

After Japan’s surrender MIS-trained specialists assisted in demobilizing Japanese military personnel returning from oversea outposts, and they provided services that aided in the arrest and prosecution of Japan’s military leaders during the 1945–1948 Tokyo War Trials. But the service of these Nisei patriots was slow to be appreciated publicly. In April 2000, five decades after World War II, the MIS was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest honor given to a U.S. military unit. Ten years later Congress approved awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to the 6,000 Japanese Americans who served in the MIS as well as to Nisei in the 100th Infantry (“Go for Broke”) Battalion from Hawaii and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (“Purple Heart Battalion”). The latter two units, merged in August 1944, served with distinction in Europe.

Japanese American Linguists Became America’s Secret Weapon During World War II

|  |

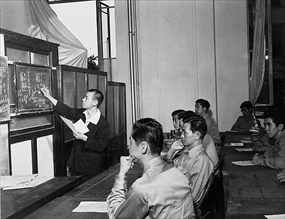

Left: The inaugural MISLS class of April 1942 at the Presidio of San Francisco in 1942. In this photo students attend a class in legal terminology as part of their training to better their knowledge of the Japanese language. The year before, in March and April 1941, discussions and informal plans were formulated for establishing a school for Nisei enlisted men who were conversant in Japanese. Facing the probability of war with Japan, the U.S. War Department in late summer 1941 directed the Fourth Army on the West Coast to implement the plan for a Japanese language course to train soldiers to become Army interrogators, interpreters, and translators who could remove language difficulties in prosecuting a war against Japan. (This was all top secret until many years after the war.) The Fourth Army Intelligence School, as the language school was initially known, was established a few buildings from Fourth Army Headquarters (soon to become the HQ of the Western Defense Command) at the Presidio in San Francisco, California. The school opened in an abandoned airplane hangar on November 1, 1941, with 58 Nisei and 2 Caucasian students and 4 teachers but had little funds ($2,000), hardly any textbooks, no chairs, no tables, borrowed typewriters, paper, and few supplies. Given the shortage of texts at the time, students studied from mimeographed sheets. The school nearly shut its doors when the War Department issued orders that no Nisei would be allowed to serve overseas. The order was rescinded.

![]()

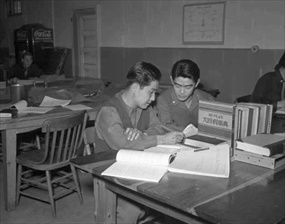

Right: MISLS students Isami Sam Osato and George Ryoichi Sakanari translate Japanese civil service regulations into English in a classroom exercise at Fort Snelling, c. 1944. Camp Ritchie, which trained German-language linguists as interrogators, interpreters, and translators, was MISLS’s equivalent in Maryland on the U.S. east coast.

|  |

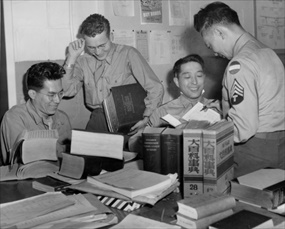

Left: A team of translators practice their skills at the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Fort Snelling, 1945. (The sergeant with the three chevrons and “T” on his sleeve is technician fourth grade, T/4 or Tec 4.) In the same year Fort Snelling enrolled about 40 Nisei WACs (Women Auxiliary Corps), 13 of whom were deployed to Japan to serve in the MIS in occupied Japan.

![]()

Right: Posing with semiautomatic M1 Garands MISLS graduates Technical Sergeants Herbert Yoshiki Miyasaki and Akiji (Akigi) Yoshimura flank Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill, Northern Burma, May 1, 1944. Hawaiian-born Miyasaki was Merrill’s personal interpreter. Some of the most celebrated Nisei of the war fought with the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), better known as Merrill’s Marauders, between February and August 1944. Three of 14 Nisei linguists assigned to Merrill’s Marauders 50‑man intelligence and reconnaissance (I&R) platoons—Camp Savage classmates Hiroshi Roy Matsumoto (recruited like three other team members from U.S. internment camps), Henry “Hank” Gosho, and Grant Hirabayashi—were inducted into the Army Rangers Hall of Fame. (Matsumoto was awarded the Legion of Merit, the prestigious medal pinned to his chest by Merrill himself.) Merrill’s jungle-trained officers and men became famous for their long-range penetration missions deep behind Japanese lines, often engaging Japanese forces superior in number. Throughout combat in the Asia Pacific area Nisei linguists were accompanied by one or more Caucasian soldiers to ensure that the Army’s “eyes and ears,” as Merrill called his Nisei linguists, were not mistaken for the enemy and shot by other GIs.

|  |

Left: Embedded with the U.S. 32nd Infantry (Red Arrow) Division MIS-trained linguists Sinao Phil Ishio and Arthur Katsuyoshi Ushiro interrogate a prisoner taken in the Battle of Buna-Gona, Papua New Guinea, January 2, 1943, the day Buna was taken. In countless instances information from POW interrogations produced vital tactical information such as maps, operational orders, location of machine guns, mortars, and other weaponry), largely due to the average Japanese soldier not knowing his rights under the 1929 Geneva Convention (provide only name, rank, and serial number), which by the way Japan (and the Soviet Union) refused to ratify.

![]()

Right: MISLS graduate Lt. Torao Pat Neishi, who first saw combat in late 1942 during the Battle of Buna-Gona, discusses surrender terms with a Japanese lieutenant general somewhere east of Manila, February or March 1945. Given Bushidō (Way of the Warrior), the samurai code of honor that considered surrender a disgrace, taking Japanese prisoners was a rarity—35,000 POWs between 1942 and 1945—compared with 945,000 German and 490,000 Italian POWs taken captive during the war in Europe. For instance, in the 5-week Battle of Iwo Jima (February 19 to March 26, 1945) only 216 enemy prisoners were captured out of the 20,530–21,060 island defenders. U.S. Army soldiers of Japanese descent captured on the battlefield in the Pacific and Southeast Asia theaters were treated as Japanese traitors to the emperor rather than American POWs. Their fate, it was said, was to die a tortured death.

Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service in World War II (Skip first 13 seconds)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click