NAZIS DRIVE TOWARD UKRAINE, OILFIELDS

Wolf’s Lair, Fuehrer HQ, East Prussia · August 23, 1941

On this date in 1941 at his concealed East Prussian “Fuehrer Headquarters” in the Rastenburg swamps, Adolf Hitler made a decision that doomed Operation Barbarossa—his planned liquidation of the Soviet Union. Barbarossa had been launched two months earlier, on June 22. But after three weeks of disagreeing with his generals regarding the most urgent objectives of his campaign (Leningrad [today’s St. Petersburg]), because of its key position on the Baltic; Kiev, capital of the agriculturally rich Ukraine and gateway to the Caucasus oilfields; or Moscow, center of Soviet political power), Hitler ordered Field Marshal Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center to make a ninety-degree turn and march south to the Ukraine. War, he chided his generals, was above all an economic event. The generals, von Bock and particularly Gen. Heinz Guderian, who had held a field command during the invasion of Poland, where he was able to perfect the idea of lightning war (blitzkrieg) and used it spectacularly in the opening months of Barbarossa, complied. But they sensed that, after expending enormous energies, men, and materiel that would be involved in taking the Ukraine, they would have to fight a winter campaign to take Moscow. (Guderian had been poised to assault Moscow after his 2nd Panzer Group captured Smolensk, 250 miles west of the Soviet capital, on July 16, 1941.) Operation Typhoon, the Axis assault on Moscow, began on the last day of September. Arrayed against Moscow was roughly half of Germany’s Eastern Front force, outnumbering the defenders in almost all respects. But snowfalls, which began on October 6, favored the defenders. Before mud could freeze to the advantage of the mechanized German advance, the Soviets had strengthened the capital’s defenses. Once the full fury of the Russian winter struck, which was the coldest in over 50 years, the Axis armies quickly became unable to conduct further combat operations, with more casualties resulting from cold weather than from battle. The Soviet counteroffensive soon drove the Axis armies into retreat. Operation Typhoon was Hitler’s first major land defeat, and it marked the beginning of the failure of Guderian’s blitzkrieg as a strategy. Of the three Soviet cities fixed in Barbarossa’s crosshairs, only Kiev succumbed to the Germans.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1612001203,0971385238,0813134161,1612002188,1781590702,1107035120,052117015X,0312628196,141657350X,0764343769″ /]

German Invasion of the Soviet Union Stopped Cold by 1941 Russian Winter

|

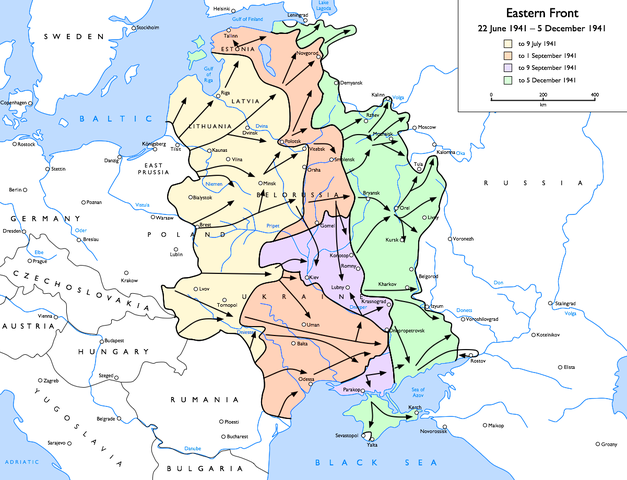

Above: Map of German operations against the Soviet Union, June 22 to December 5, 1941. Operation Barbarossa was the largest military operation in history in both manpower and casualties.

|  |

Left: Armed with heavy shovels, a hastily assembled work force of Moscow women, teenagers, and elderly men gouge a huge tank moat out of the earth to halt German panzers (armored units) advancing on the Soviet capital. In the feverish effort to save the city, some 250,000 citizens labored from mid-October until late November digging ditches and building other obstructions. When completed, the ditches extended more than 100 miles.

![]()

Right: Muscovites installed anti-tank barricades on city streets in October 1941. Between October and the end of November, the capital remained within reach of German panzers, which never came. Moscow was, however, the object of massive air raids, though these caused only limited damage because of extensive anti-aircraft defenses and effective civilian fire brigades.

|  |

Left: German soldiers pull a staff car through heavy mud on a Russian road, November 1941. Hitler, arrogant and ruinously overconfident owing to his blitz of successes in Western Europe, expected a victory in the east within a few months, and therefore he did not prepare his Wehrmacht for a campaign that might last into a wet late fall, much less a bitterly cold winter. The assumption that the Soviet Union would quickly capitulate proved to be his, and Nazi Germany’s, tragic undoing.

![]()

Right: On December 2, 1941, the first blizzards of the Russian winter began just as one unit of the Wehrmacht caught glimpse of the spires of Moscow’s Kremlin 15 miles away. That same day a reconnaissance battalion crept to within 5 miles of Moscow, but that was as close to the military prize as any Wehrmacht unit managed. In this photo a Panzer IV tank in white camouflage is stranded in deep Russian snow as its crew attempts to free it. At the right edge of the photo is a war correspondent who filmed the scene for audiences back in Germany.

|  |

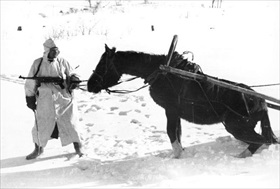

Left: A German soldier with machine-pistol and white winter coat tugs at a horse pulling a cart in a snow-covered landscape west of Moscow. Horse-drawn supply transports as well as combat units were equally stopped by first autumn mud, then deep winter snow and arctic temperatures. Heinz Guderian wrote in his journal: “The offensive on Moscow failed. . . . We underestimated the enemy’s strength, as well as his size and climate. Fortunately, I stopped my troops on 5 December, otherwise the catastrophe would be unavoidable.” For his efforts Guderian was relieved, along with 40 other generals, of his command on December 26, 1941.

![]()

Right: Two German soldiers in heavy snow on guard duty west of Moscow, December 1941. December’s low temperature reached -20°F. More than 130,000 cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers. The same weather hit Soviet troops, but they were better prepared for the cold.

Following Initial Successes, Hitler’s Wehrmacht Prepares to Advance on Moscow

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click