NAZI V-1 FLYING BOMBS TERRORIZE LONDON

London, England · June 13, 1944

Beginning on this date in 1944 in London, one week after the Allied D‑Day landings in Normandy, France (Operation Overlord), the Germans unleashed their pilotless flying “retaliation weapon,” Vergeltungswaffe‑1, on England. Adolf Hitler crowed to his rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun, “This will be retribution against England. With it we will force England to her knees.” Only one of ten V‑1 flying bombs launched that day from bases in the Pas de Calais region opposite the English port city of Dover caused any casualties—six civilians killed and nine injured when a V‑1 struck next to a railway bridge. A week later more than 500 of these new weapons had hit Southeast England—244 falling on London on June 19—killing hundreds of people and injuring thousands more. Exacting revenge for the massive Allied aerial bombing of Germany appeared off to a good start.

Conceived in 1937 as a radio-controlled flying drone for use in target practice, these “buzz bombs,” so-called for the rhythmic coughing and putt-putting sound their pulsejet engine made, turned into one of the crudest and simplest terror weapons ever built. They were also relatively cheap to make. Constructed of plywood overlaid with sheet metal, they did not require scarce aluminum. Equipped with a rudimentary gyroscope to keep them flying straight at between 2,000 and 3000 feet/610 and 914 meter over the Channel, the “buzz bombs” (also known as “doodlebugs” and “divers”) fell indiscriminately over a large target area when their engine cut out and the bombs went into a steep dive. With an operating speed of 400 mph/644 km/hr, they were difficult to bring down at first. A barrage balloon belt fitted with extra cables south and east of London wasn’t terribly effective, bringing down only 300 (15 percent) that reached the area. In mid-July 1944 London’s whole antiaircraft belt was moved down to the coast. These flak guns were effective when paired with the simple computers of the time.

RAF pilots flying souped-up, stripped-down Spitfires developed a technique of “tipping” a V‑1, meaning a pilot approached the flying bomb and tipped his wing onto that of a V‑1 to knock it off balance, sending the thing careening to earth where it exploded on impact with the ground. The most successful pilot downed 60 of these cruise missiles this way. (Pilots had to consider whether there was any friendly fire from antiaircraft batteries in the area before engaging in this daring-do.) Hitler hoped the daily rain of these death-dealing, 2‑ton missiles would force London’s evacuation (1 million mostly women, children, the aged or infirm did leave), weaken Britain’s resolve to stay in the war, and snatch a German victory from the jaws of looming defeat after the Western Allies had firmly established themselves on the European continent in mid-1944.

Launched from fixed sites in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France (more than 50 on the French Pas de Calais coast alone) or from aircraft, 3,531 flying bombs reached England, with 2,420 falling on Greater London. At its peak, over a hundred V‑1s were fired each day at Southeast England, which acquired the sobriquet “Hell Fire Corner.” The 2‑ton flying bombs with their 1,870 lb/848 kg warheads killed 6,184 people, seriously injured another 17,981, and destroyed or damaged over 1.1 million structures until the last V‑1 launch site in range of the British Isles was overrun by Allied forces in October 1944.

The successor to the V‑1 proved even deadlier—a true shock-and-awe weapon feared for its supersonic speed (1,790 mph/2,880 km/hr at impact), silent approach from 50–120 miles/80–208 kilometer high, and awful devastation. About 3,500 V‑2 rockets were fired at London and other cities between September 8, 1944, when the first V‑2 landed on British soil, and the end of March 1945.

V-1 “Buzz Bombs”—Nazis’ Crude, Cheap, Simple Terror Weapon

|  |

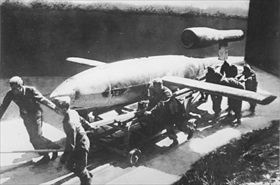

Left: A German crew rolls out a V‑1 in 1944. The V‑1 resembled a miniature stubby-wing fighter plane with no cockpit. It carried a 1‑ton, high-explosive warhead. Atop its tail was a stovepipe pulsejet engine that burned 80 percent octane gasoline. As its fuel ran out, the V‑1 plunged to earth and exploded with devastating effect. The Germans manufactured close to 32,000 of these 25‑foot/7.9‑meter-long flying bombs, the first in what the Germans called their “secret weapon.” (The second of course was the V‑2 ballistic missile.) V‑1 launch sites in France were located in nine general areas, four of which had launch ramps aligned toward London, and the remainder toward Brighton, Dover, Newhaven, Hastings, Southampton, Manchester, Portsmouth, Bristol, and Plymouth. To help counter the V‑1 threat, 23,000 men and women with antiaircraft guns, radar, and communication networks were installed along the English coast. RAF squadrons, consisting of the newest Spitfires, Hawker Tempests, and even Gloster Meteor jets, were also employed. Together these defenses destroyed 3,957 V‑1s.

![]()

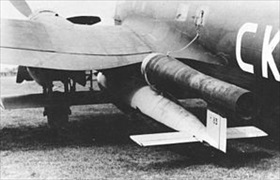

Right: Luftwaffe Heinkel He 111 H-22 twin-engine bombers air-launched V‑1s from low altitude over the North Sea toward Britain. Only a few of these aircraft were produced in 1944, when bomber production was largely halted in favor of fighter aircraft. The majority of V‑1s were launched from contraptions that resembled roller coasters whose tracks suddenly halted on the upgrade. In operation, the V‑1 jet engine would be started and the flying bomb steam-catapulted off 157‑foot/48 meter-long tracks pointing directly to its target.

|  |

Left: V-1s gave off a telltale glow from their tails. Altogether 10,500 were launched against Britain during the war. Little more than half hit their targets (the figure also includes V‑2s). Bomb disposal teams were dispersed to sites where V‑weapons had failed to explode on impact in order to render them harmless. The last V‑1 launch site was overrun on March 29, 1945, five weeks before war’s end. V‑1s were assembled near Wolfsburg, at the Mittelwerk underground factory and at Allrich in Central Germany, at Barth close to the Baltic Sea, and in the Buchenwald concentration camp complex (V‑1 parts).

![]()

Right: From captured V‑1 components both Americans and Soviets built versions of the German cruise missile. Even the Japanese got into the cruise missile game when the Germans, using a U‑boat, shipped them a pulsejet engine. The Baika (“Plum Blossom”) never left the design stage. The American version of the German V‑1 was a prototype known as the “Loon,” seen here being launched from a B‑17 Flying Fortress during weapons testing in 1944. The intention was to use these flying bombs as a key component of Operation Downfall, America’s knockout punch to Japan set to kick off in October 1945. Plans were to produce 1,000 per month. Two U.S. bombs of a radically different nature, dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, meant no Loons were ever used against Japan.

The V-1 Flying Bomb: The Nazi Cruise Missile

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click