NAZI MASSACRE IN RUMBULA FOREST

Riga, German-Occupied Latvia • November 30, 1941

On November 25 and 29, 1941, Einsatzgruppe 3 (Special Task Group 3), one of many SS (short for Schutzstaffel) mobile death squads operating behind German front lines, murdered5,000 “Reich Jews,” that is, German- and Austrian-born Jews. These men, women, and children had arrived in the Baltic ghetto at Kaunas, Lithuania’s second largest city, earlier in the month. (The tiny Baltic states of [north to south] Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and formerly Soviet Socialist Republics after their occupation by the Red Army in 1940, as well as parts of Northeastern Poland and the western part of Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (now Belarus), made up the German administrative district of Reichskommissariat Ostland between 1941 and 1945.)

On this date, November 30, 1941, in the Rumbula Forest 9 miles/14½ km south of Riga, capital and major city of the neighboring Baltic state of Latvia (and seat of the Reichskommissariat Ostland), the first of 2 sets of even more horrific mass murders began. (The second set occurred the following month, on December 8.) Roughly 24,000 of the victims were so-called (by the Nazis) “unproductive” (“unwertvoller”) Latvian Jews from the overcrowded Riga Ghetto, a 16‑block area known as Maskavas Forštate (Moscow Suburb), where 32,000 lived. Additional victims were approximately 1,000 Reich Jews who had left Berlin 2 days before on the first of 19 transport trains to Riga. Second only to the Babi Yar massacre in the Soviet Ukraine (September 29–30, 1941, when Germans and local collaborators killed 33,771 Jews in a single operation), the Rumbula massacre was the biggest 2‑day Holocaust atrocity until Nazi Germany introduced extermination camps in Poland in 1942.

The Rumbula massacre was carried out by Einsatzgruppe A, which was assigned to Army Group North commanded by Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, whose forces had overrun the 3 tiny Baltic states in June and July 1941 and began an 874‑day siege of the Soviets’ Baltic port and second largest city, Leningrad (part of Operation Barbarossa) on September 8, 1941. Einsatzgruppe A was aided by a unit of Latvians known as the Arajs Commando and to some extent by Latvian auxiliary police. Of the 40,000 Jews living in Riga (about 10 percent of the city’s population) when the Germans invaded the Baltic states in July 1941, only 4,800 were still alive by the end of the year. By late 1943 almost all Latvian Jews (out of approximately 66,000 at the start of the Nazi occupation) had perished in further SS “actions” (the Nazi euphemism for murder; for example, in gas vans), or had been worked to death in Latvia’s infamous Salaspils concentration camp, 11 miles/almost 17 km from Riga, or had been transported to other concentration and death camps.

Holocaust in Riga, Latvia, 1941–1945

|

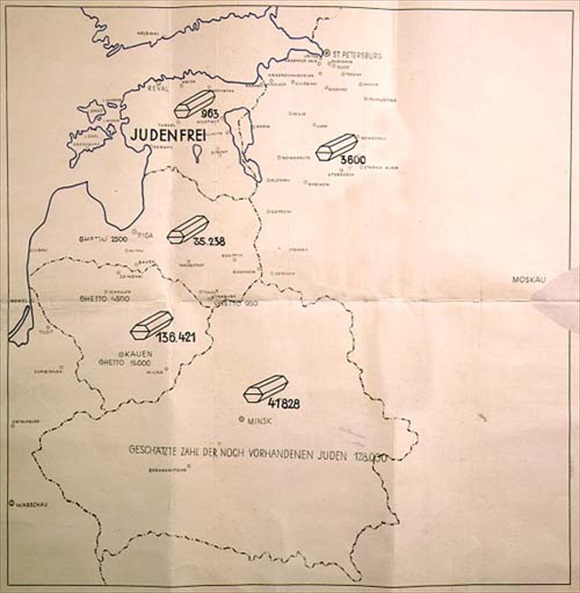

Above: Sketch map of Baltic States and Eastern Europe used to illustrate SS-Brigadefuehrer und Generalmajor der Polizei Dr. Franz Walter Stahlecker’s report titled “Jewish Executions Carried Out by Einsatzgruppe A” and stamped “Secret Reich Matter.” On January 31, 1942, the report was sent to Stahlecker’s superior, SS-Obergruppenfuehrer and General der Polizei Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Security Head (or Main) Office (which included the Secret State Police, or Gestapo). The map summarized the number of murders committed by Stahlecker’s SS unit in the Baltic states and the Soviet Union in 1941; namely, 220,250. The legend at the bottom states that “the estimated number of Jews still on hand is 128,000.” Estonia in the north is marked “JUDENFREI” (“free of Jews”) (963 killed); Latvia (35,238 killed); Lithuania (138,421 killed); Belarus (41,828 killed); and Russia (3,800 killed).

|  |

Left: Riga ghetto in 1942. After the mass execution at Rumbula and the liquidation of the so-called “large ghetto,” Latvian survivors moved into a smaller ghetto, which also housed deported Reich Jews from Germany, Austria, and today’s Czech Republic (Bohemia and Moravia). Its barbed-wire perimeter was guarded by Latvians. Within the smaller ghetto, the Germans maintained a special company of guards, consisting of policemen from Danzig, today’s Gdańsk in Poland. Jewish Councils (pl, Judenraete; sing, Judenrat), 1 for the Latvians and 1 for the Germans, were set up to work with the German occupation authorities (Gestapo and Wehrmacht). A Jewish Ghetto Police force was also established for each community. The Nazis set up a Labor Authority, which liaised with the Judenraete. Every morning Jewish work crews assembled in the streets according to their work assignments.

![]()

Right: 1942 photo showing Jews in Riga wearing the required yellow 6‑pointed star, 1 star visible from the front, the other from the back (man in long dark coat, center in photo). Jews were forbidden to use streetcars and sidewalks, which made it dangerous for automobile drivers and Jewish pedestrians alike, and were banned from public places, including city facilities, parks, and swimming pools. Also, a Jew was allotted only one-half the food ration of a non-Jew. Nuremberg-style race laws were introduced governing marriage and employment, and Jews could be randomly assaulted with impunity by any non-Jew. An account from the year 1943 lists 13,200 Jews in the Riga ghetto. By the end of November 1943, all Jews had been removed, either by transport to a concentration or death camp (2,000 to Auschwitz on November 2, 1943) or by murder. Throughout 1943 and 1944 the Red Army gradually recaptured most of the Reichskommissariat Ostland in their drive on Hitler’s Germany.

Riga Ghetto—Holocaust Survivor Alex Lebenstein’s Story

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click