NAZI, FASCIST FOREIGN MINISTERS HUDDLE

Salzburg, Austria · August 11, 1939

On this date in 1939 near Salzburg, Austria, Adolf Hitler’s foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop told Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s foreign minister, Galeazzo Ciano, about Hitler’s decision “to set Europe on fire.” “We want war,” Ribbentrop said to Ciano, though he omitted saying that Hitler had just signed the order to occupy the League of Nations-administered Free City of Danzig (see map below) and had mobilized the German army along the German-Polish frontier. The meeting between Ribbentrop and Ciano, a substitute for a summit of the two dictators canceled the week before, was to impress on Mussolini that there would be no “second Munich”—a reference to the 1938 conference of leaders from Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy (in attendance were Ribbentrop and Ciano) that garnered Germany only a sliver of Czechoslovakia, namely, German-speaking Sudetenland. (Later in November the two foreign ministers parceled out more Czech territory and citizens when they “supervised” the transfer of 5,000 sq. miles and over one million inhabitants to Hungary, many of them not even Hungarians.) The next day, August 12, Ciano visited Hitler at his luxurious Alpine residence, the Berghof, where he cautioned Hitler of the harm war would inflict on the Italian people. Later in the month Hitler separately confirmed his decision to attack Poland without giving Mussolini the date. On Friday, September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland and Danzig, Mussolini wrote Hitler that he was worried their joint military and economic alliance, the so-called “Pact of Steel” that Ciano and Ribbentrop had initialed in Berlin in May 1939, would drag an unprepared Italy into the conflict, and he wanted to bail out. Mussolini was reassured when Hitler promptly cabled back that Italian troops were not needed in Poland. Mussolini told Hitler that Italian intervention would only be possible were Italy given sufficient military materiel and raw materials (e.g., molybdenum, oil, and rubber) to withstand French and British attacks, which would surely come now that both democracies had declared war on Germany (September 3, 1939). Italy, which all along had expected to be involved in a European war after 1942, stayed out of the conflict until June 10, 1940, when Mussolini’s greed to share in the spoils of war spurred a change of heart.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0521338352,0813118034,1929631421,0275979377,1439132348,0143120069,041573410X,0811708284,0061228605,0471591513″ /]

Countdown to War, 1939

|  |

Left: The “Polish Corridor,” which provided Poland access to the Baltic Sea via territory that had previously been Prussia, cut post-World War I Germany in two. Germans were required to carry a passport when paying an overland visit to East Prussia. To the east of the corridor lay the Free City of Danzig (today’s Gdańsk), which was under League of Nations protection and in a binding customs union with Poland.

![]()

Right: After the four major European power brokers agreed in Munich in September 1938 to split German-speaking Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, Germans in the Danzig enclave, where they made up 95 percent of its population, requested reunification with the Third Reich. Great Britain’s Neville Chamberlain and France’s Édouard Daladier (both to Hitler’s right in this 1938 photo) consigned the fate of their countries to politicians in Warsaw in 1939 when they offered to take any action that threatened Poland’s independence. Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck saw the British guarantee as putting Hitler in his place, though it was impossible for Poland’s two allies to provide any effective protection.

|  |

Left: German troops remove Polish insignia at the Polish-Danzig border near Sopot (German, Zoppot), September 1, 1939. The following day the Free City of Danzig was annexed by Nazi Germany and most of the local Poles, Slavs (Kaszubians), Jews, and opposition leaders were arrested and sent to concentration camps or expelled. As many as 110,000 people were deported to nearby Stutthof concentration camp, which was completed on September 2, 1939, and 85,000 victims perished there.

![]()

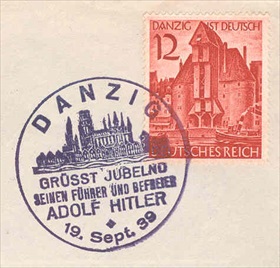

Right: “Danzig is German” stamp issued by Nazi postal authorities to celebrate Danzig’s return to the German fatherland. The cancellation mark, dated September 19, 1939, reads, “Danzig jubilantly greets its Führer and liberator Adolf Hitler.”

Invasion of Poland, September 1939

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click