NAVY SET TO RECRUIT CIVILIANS INTO SEABEE UNITS

Washington, D.C. · December 28, 1941

The Seabees were in effect combat engineers of the U.S. Navy, working and, when necessary, fighting on land. On this date in 1941 Rear Admiral Ben Moreell requested authority to organize a militarized Naval Construction Force, and a week later he gained permission from the Bureau of Navigation (later called the Bureau of Naval Personnel) to recruit men from the construction trades (surveyors, civilian engineers, carpenters, plumbers, steam-shovel operators, truck drivers, and the like) for assignment to one of several new Naval Construction Battalions. The battalion’s popular name—Seabees—derives from the initials “CB” for Construction Battalions, which was their official designation. On August 11, 1942, the Naval Construction Training Center, known as Camp Endicott, was commissioned at Davisville, Rhode Island, and trained over 100,000 Seabees during the war. Four months earlier a base for supporting the Naval Construction Force was established at Port Hueneme, California. This base became responsible for shipping 20 million tons of equipment and war materiel and a quarter of a million men to support Allied operations in the Pacific. At first Seabees were civilian volunteers, though, draftees joined later. Because of the emphasis on experience and skill rather than physical standards, the average age of Seabees during the early days of the war was 37. More than 325,000 men served with the Seabees in all theaters but mainly in the Pacific. Typically Seabees would land very shortly after the initial assault force and immediately begin work on building airstrips, bridges, roads, gasoline storage tanks, cargo and docking facilities, piers, pontoon causeways, and Quonset huts for warehouses, hospitals, housing, and other base facilities. The men operated under fire and frequently were forced to take part in the fighting to defend themselves and their construction projects. Without their efforts neither the D‑Day landings in Normandy (Operation Overlord) nor the island-hopping strategy that led to victory over Japan would have been possible.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0595456359,1456476033,1557503796,1466367393,1557503486,1460949641,0738553069,0738531200,1479153818,0738501069″ /]

U.S. Navy Seabees in the Pacific Theater, 1942–1945

|

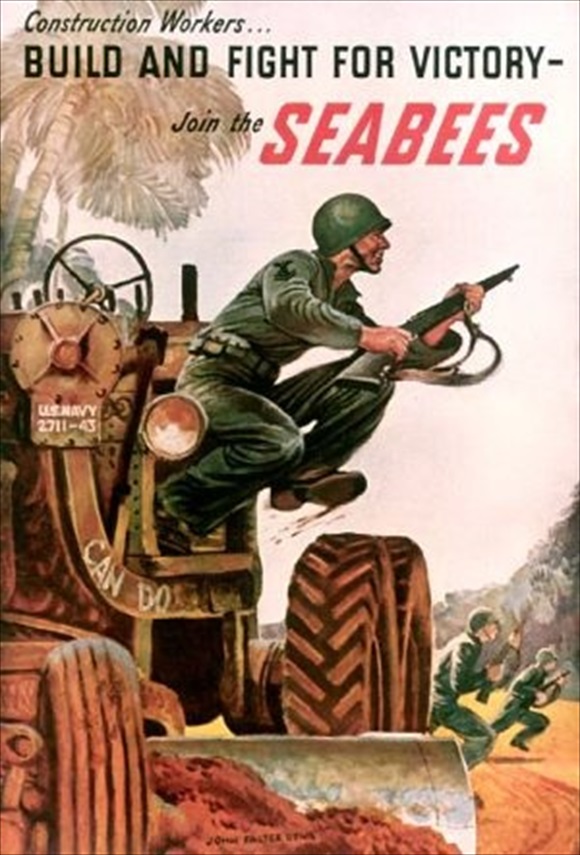

Above: With their “Can Do!” motto, Seabees brought the war to the enemy’s home turf and waters. They served on four continents and on more than 300 islands, ranging from South America and the Caribbean, to the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean, Europe, Alaska and the Aleutians, and the Pacific. By the end of World War II, 325,000 men, representing more than 60 skilled trades, had enlisted in the Seabees.

|  |

Left: Seabees practice constructing a sand roadway at Camp Peary, Virginia. After completing three weeks of boot training at Camp Allen, and later at its successor, Camp Peary, both in Virginia, Seabees were formed into construction battalions or other types of construction units. A standard construction battalion originally was set at 32 officers and 1,073 men, but from time to time the complement varied in number. As the war progressed and construction projects became larger and more complex, more than one battalion frequently had to be assigned to a base. For efficient administrative control, these battalions were organized into a regiment, and when necessary, two or more regiments were organized into a brigade, and as required, two or more brigades were organized into a naval construction force. For example, 55,000 Seabees were assigned to Okinawa and the 190 battalions were organized into 11 regiments and four brigades.

![]()

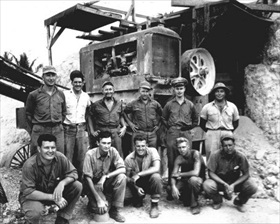

Right: This group of African American Seabees trained at Camp Allen and Camp Bradford near Norfolk, Virginia, where they were taught, as were all Seabees, military discipline and the use of light arms. Although technically support troops, Seabees, particularly during the early days of base development in the Pacific, frequently found themselves in conflict with the enemy.

|  |

Above: In the North, Central, South, and Southwest Pacific areas, the Seabees built 111 major airstrips, 441 piers, 2,558 ammunition magazines, 700 square blocks of warehouses, hospitals to serve 70,000 patients, tanks for the storage of 100 million gallons of gasoline, and housing for 1,500,000 service members. In construction and fighting operations, the Pacific Seabees suffered more than 200 combat deaths and earned more than 2,000 Purple Hearts.

|  |

Above: In the photo on the left, Seabees are laying the foundation for (most likely) a Quonset hut. On the right, members of the 61st Seabees have erected a Quonset village at Tolosa on Leyte Gulf, which provided quarters, offices, and communication facilities for the U.S. Seventh Fleet and the Philippine Sea Frontier headquarters during the last months of the war.

Rear Admiral Ben Moreell Introduces Documentary on U.S. Navy Construction Battalions, or Seabees

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click