NAVY FLIERS FIND RICH TARGETS IN MARIANAS

Off the Mariana Islands, Central Pacific · June 12, 1944

On this date in 1944 in the Marianas, U.S. carrier aircraft began attacking Japanese defenses on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in preparation for the three-week battle on Saipan. On July 9 U.S. Marines declared Saipan secured, calling the battle for the island “the decisive battle of the Pacific offensive.” The Japanese defeat in the Marianas ripped a hole in Japan’s Pacific inner defensive circle, the so-called “Absolute National Defense Zone,” once considered essential by the country’s military leaders to continue the war and protect the Japanese Home Islands (Hokkaidō, Honshū, Kyūshū, and Shikoku, comprising an area the size of California). Gone now were the Japanese forward bases in the Central Pacific, making the American submarine blockade of Japan more effective than ever. In the first six months of 1944, U.S. submarines sank over 300 enemy freighters. During all of 1944 Japan managed to import just 5 million barrels of oil, although the nation consumed over 19 million barrels. Nineteen forty-four saw the total tonnage of Japanese imports shrink to less than half that of 1941. The war guidance unit of the War Ministry at the Imperial General Headquarters reached three conclusions: First, the empire had no prospect of regaining its previous strength; secondly, strength would gradually decline; and, thirdly, the nation’s leaders should seek an end to the war immediately. Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō and his war cabinet resigned in disgrace, but his successor, Gen. Kuniaki Koiso (July 22, 1944, to April 7, 1945), believed that Japan needed to win a battle against the U.S. in the Philippines to gain leverage in any peace negotiations. Koiso’s hopes were crushed in the Battle of Leyte Gulf (October 23–26, 1944), which involved nearly 500 ships; it was the most sprawling and spectacular naval battle in history. When the smoke cleared, the Japanese had lost most of what remained of their naval and air power. The U.S. went on to take the Philippine’s main island of Luzon, which allowed the U.S. to further cut off the sea lanes between the Japanese Home Islands and the imports the Japanese economy and war machine desperately needed. By the end of 1944, the number of U.S. submarines in the Pacific alone stood at 200. Japanese soldiers in the Philippines joked that one could walk from the Philippines to Japanese-held Singapore on the tops of U.S. submarine periscopes.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0813141109,0253348692,0891418040,1612000940,1841768049,1557502439,0306813696,0451219562,1591149762,0451219562″ /]

The Mariana Islands Campaign, June–August 1944

|

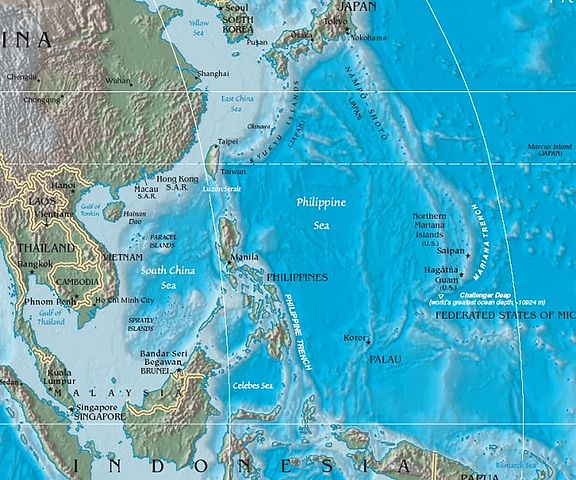

Above: The arc-shaped Mariana archipelago in relation to Japan (to the north), New Guinea (to the south), and the Philippine Sea (to the east).

|  |

Left: One day before U.S. Marine Lt. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith declared Saipan secure, U.S. Marines are shown here taking cover behind a M4 Sherman tank in an operation to clean out the northern end of the island. Although major fighting had officially ceased on July 9, 1944, pockets of Japanese resistance continued, and in September Marines began patrols into Saipan’s interior to extract soldiers and civilians still holding out in the jungles.

![]()

Right: Roughly 400–500 Native Americans in the U.S. Marine Corps transmitted tactical messages over military telephone or radio communications nets using formal or informally developed codes built upon their native languages. Navajo code talkers were the most famous of the code talkers, but Cherokee, Choctaw, Lakota, Meskwaki, and Comanche code talkers were employed as well. Even speakers of Basque, a European language, were used to encode and decode messages.

|  |

Left: The U.S. victory on Saipan made nearby Tinian the next logical step in the Marianas campaign. In this photo Marines wade onto Tinian’s beaches. The battle to secure the island lasted from July 24 to August 1, 1944. It was from Tinian’s “North Field” that the Enola Gay and Bockscar began their epic missions to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively.

![]()

Right: An amphibious landing craft known as a Water Buffalo (aka, Landing Vehicle Tracked [LVT]), loaded with Marines, churns through the sea bound for Tinian’s beaches, July 1944.

|  |

Left: Eight minutes after Marines and Army assault troops landed on Guam, the largest of the Marianas, on July 20, 1944, two GIs planted the American flag. Fighting on Guam ended on August 10, 1944.

![]()

Right: Marines on Guam show their appreciation to the U.S. Coast Guard. During amphibious landings in the Pacific, European, and Mediterranean theaters, a large percentage of the landing craft coxswains were Coast Guard-enlisted men, who brought men and supplies ashore and returned with the wounded and dead. Coast Guardsmen also manned or partially manned assault transports as well as landed with Marines on Pacific beaches.

Battle of Saipan, Marianas Islands, U.S. Army Pacific Island Hopping Campaign

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click