NAGASAKI LEVELED BY U.S. A-BOMB

509th Composite Group HQ, Tinian, Mariana Islands · August 9, 1945

Despite the shockwaves that Hiroshima’s destruction on August 6, 1945, sent through Imperial circles, Japan’s government refused to agree to an unconditional surrender, their leaders insisting on preconditions that protected the status of Hirohito as emperor. (Had there been no Japanese foot-dragging, would the Pacific War have been over before August 6 or perhaps August 8?) The Soviet declaration of war on August 9 and a fast-moving Red Army invasion of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo and North Korea shattered any expectation that Japan’s large army on the Asian mainland could hold back her enemies’ conventional forces, yet even that failed to move Japan’s warlords.

After dropping millions of leaflets and after hours of radio broadcasting from American-held Saipan Island warning Japan of further devastating raids following Hiroshima’s destruction, to no avail (the 48‑hour deadline to hear back had expired), the U.S. settled on exploding a second, more powerful atomic device over Kokura (present-day Kitakyūshū) on this date, August 9, 1945. (Kokura was the location of one of the largest arsenals still standing in Japan.) Bockscar, the B‑29 carrying “Fat Man,” as the plutonium‑239 bomb was nicknamed, circled Kokura three times but did not drop its lethal payload due to cloud cover, industrial haze perhaps, and smoke drifting east over the city after an incendiary raid by over 200 B‑29s on nearby Yahata (Yawata) (“the Pittsburgh of Japan”) less than 24 hours before.

Because of fuel constraints, Bockscar turned south and flew to its backup target, Nagasaki, a large industrial port city, also on Kyūshū. That city was also covered by the same storm system, but at the last minute the bombardier was able to secure the required visual contact with the target through a hole in the clouds. The bomb destroyed about 44 percent of Nagasaki, killed perhaps 35,000, and injured 60,000 out of 263,000 who were there that day. Further aerial immolation of Japanese cities was averted in part by a 9‑day U.S. propaganda campaign that included radio broadcasts and air-dropping 5–6 million leaflets that graphically described what remained of the two cities. The leaflets caused conditions close to panic in some cities.

By now U.S. air raids had killed 600,000 Japanese civilians. The carnage stopped at noon August 15 (Tokyo time), 1945, when Hirohito addressed his subjects by radio in courtly, Orwellian doublespeak. A lover of peace (the name of his reign, Shōwa, means “bright peace”), Hirohito said it was “far from Our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.” Approximately 4.4 million military and 24 million civilian deaths later, the emperor had no words of apology for what his subjects had done to “assure Japan’s self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia.” The words “surrender” and “defeat” never crossed his lips, which left some listeners wondering if Japan had surrendered or if the emperor was exhorting his subjects to resist the anticipated enemy invasion. But surrender Japan did on August 15, ending World War II and his nation’s nearly half-century of aggression in Asia and the Pacific.

Nagasaki: Object of America’s Second Atomic Bomb, August 9, 1945

|  |

Left: Bockscar and crew delivered their own version of death and destruction when dropping “Fat Man” on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Twenty‑five-year-old Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, Bockscar’s commander, stands in the second row wearing the dark jacket. Bockscar and Enola Gay were “Silverplate” B‑29s, which were specially configured to carry nuclear weapons. They were two of 15 Silverplate B‑29s used by the 393nd Bombardment Squadron, 509th Composite Group, which carried out the two nuclear bombings.

![]()

Right: The smokestacks of Nagasaki’s sprawling Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works. The plant was located about 2,500 ft/762 m downriver from ground zero. Nagasaki’s hilly terrain tempered the bomb’s destructive effects, whereas Hiroshima was flat and open and thus suffered much greater devastation.

|  |

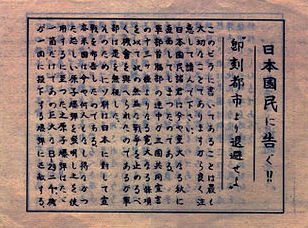

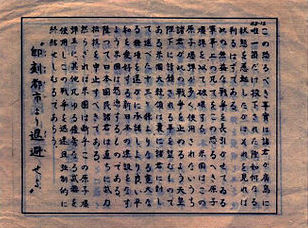

Above: Front and back of leaflets that urged the country’s quick surrender were dropped over Japan by the 509th Composite Group, a group that comprised B‑29 bombers and transport aircraft. The 509th was the United States Army Air Forces component of the Manhattan Project under the command of 30‑year-old Col. Paul Tibbets, Jr.

|  |

Left: After being assembled, “Fat Man” underwent a final procedure outside the assembly building, where exterior crevices were filled with putty and then sprayed with sealant to maintain the proper environment within the device during the time it would take to deliver it over its target. Once the sealant application had been substantially completed, workers began scrawling their names and messages on the tail fin assembly and body of the device (nearly impossible to see in this image), including one from Rear Admiral William R. Purnell, who wrote: “A Second Kiss for Hirohito!” Purnell, one of the “Tinian Joint Chiefs,” was the U.S. Navy representative on the Military Policy Committee, the three-man committee that oversaw the Manhattan Project, and the personal representative of Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.

![]()

Right: This photo shows “Fat Man” being towed to Tinian’s North Field under military police escort. On arrival the bomb was lowered by hydraulic lift into a bomb pit. Then Bockscar backed up over the pit with bomb bay doors open and the bomb was raised into the plane’s belly. In the belly prior to takeoff the bomb was armed. Before Bockscar’s commander left on his mission to Nagasaki, Sweeney ran into Adm. Purnell, who stumped him by asking the major to guess the cost of the bomb on his aircraft. Two billion dollars, Purnell stated. (Actually, it was the entire Manhattan Project that cost $2 billion.) Sweeney answered the admiral’s second question correctly when he estimated Bockscar’s value at over a half-million dollars. “I’d suggest you keep those relative values in mind for this mission,” Purnell told Sweeney.

|

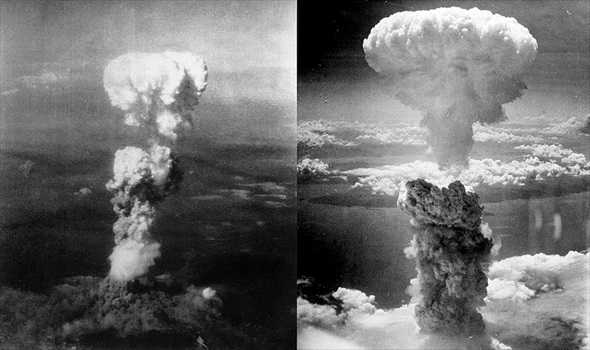

Left: At the time this photo was made, August 6, 1945, a cloud of radioactive materials billowed 20,000 ft/6,096 m above Hiroshima while it spread over 10,000 ft/3,048 m at the base of the rising column. Six planes of the 509th Composite Group participated in the Hiroshima mission: one to carry the bomb (Col. Paul Tibbet’s Enola Gay); one to take scientific measurements of the blast (The Great Artiste under the command of Maj. Charles Sweeney); and a third to take photographs (Necessary Evil). The other three flew approximately an hour ahead to act as weather scouts. Bad weather disqualified a target, as scientists insisted on a visual delivery. The primary target that day was Hiroshima. Secondary and tertiary targets were Kokura and Nagasaki, respectively.

![]()

Right: Atomic bombing of Nagasaki, August 9, 1945, by the crew of Bockscar. “Fat Man” had a blast yield equivalent to 21,000 tons of TNT, a quarter more than the device dropped over Hiroshima. The next day, August 10, the Japanese government presented a letter of protest for the two atomic bombings to the U.S. government via the Swiss embassy. It was not, however, until after the war that the full measure of the atomic horror sunk in.

Air Force Story (1953), “Air War Against Japan, 1944–1945, Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-Bombs” (May want to skip first minute)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click