MUSSOLINI REBUKES JAPANESE FOR FOOT-DRAGGING

Rome, Italy • October 8, 1941

Two months before Great Britain joined the United States in declaring war on Japan, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini used this date in 1941 to blast the Japanese for not carrying their weight in the Tripartite (Axis) Pact, a political, economic, and military agreement that Italy, Germany, and Japan had signed the year before. Italy had declared war on Great Britain and France on June 10, 1940, and joined Germany in declaring war on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, but Japan had not joined its Axis partners in declaring war on any of Germany’s and Italy’s enemies. (In April 1941 Japan had signed both a nonaggression, or neutrality, pact with the Soviet Union and another pact that pledged each nation to respect the territorial integrity of their client states north of China, Japan’s Manchukuo and the Soviets’ Mongolian People’s Republic.) Mussolini assured Tokyo that the U.S. would not come to Britain’s aid in the event of war between Japan and Britain. If Japan now failed to join the conflict against Great Britain, Il Duce (Italian, “the leader”) said, no matter which side won, the loss to be sustained by Japan “will be great.”

The Japanese waited 2 more months before unleashing a Blitzkrieg-style offensive against British as well as American interests in the Asia Pacific region. The first steps they took against the British occurred on December 8 when they bombed Singapore, the hugely important British base on the tip of the Malay Peninsula, and sent ground forces from Thailand (occupied December 9) into the British colony of Burma (present-day Myanmar) to threaten the British defense of the Indian subcontinent. Between December 10 and 13, Japanese forces moving south from their initial landings in Thailand secured major airfields in the north of Malaya. On December 16, 1941, the Japanese captured Victoria Point (today’s Kawthaung), a vital British airfield halfway up the Malay Peninsula; in so doing they cut off aerial resupply of local British forces. From Victoria Point, Japanese fighter aircraft were able to escort bombers on raids into Southern Burma, particularly against the Burmese capital of Rangoon (Yangon), 500 miles to the northwest. The Malayan capital, Kuala Lumpur, fell to the Japanese on January 12, 1942, followed by Singapore a little over a month later and Burma’s capital on March 8. By occupying French Indochina and the states to the west, the Japanese were in a preeminent position in Southeast Asia.

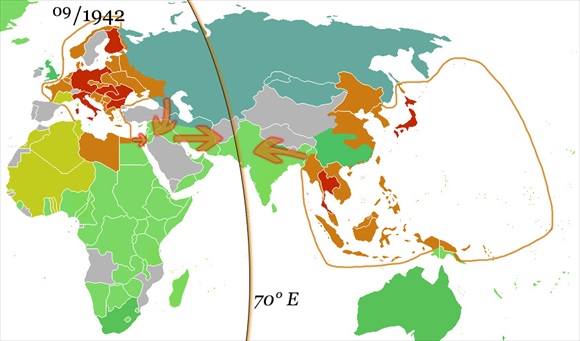

In mid-January 1942, Mussolini withdrew his criticism of Japan when the 3 Axis powers renewed their Tripartite Pact in Berlin. The pact divided the globe into areas of operation, and gave Japan complete freedom of action in all areas from the Western Pacific to the western border of India (see map).

Axis Division of the World into Spheres of Operation and Influence

|

Above: German/Italian and Japanese spheres of global reach. Arrows show planned movements of the three Axis powers, their occupied territories, and spheres of influence (red and tan) to the agreed demarcation line at 70 degrees east longitude, which was the western frontier of British India.

|  |

Left: On September 27, 1940, the Axis Powers (Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy) grew by one when Japan’s ambassador Saburō Kurusu (left in photo), Italy’s foreign minister Count Galeazzo Ciano (to Kurusu’s left), and Germany’s foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop (standing at podium at right) signed the Tripartite Pact in Berlin. Adolf Hitler (slumping in his chair) witnessed the gala proceedings. The treaty recognized the right of Germany and Italy to establish a “new order” in Europe and of Japan to impose a “new order” in Asia (see map above). Interestingly, Kurusu was Japan’s “special envoy” to Washington, D.C., in the 3‑week run-up to Japan’s surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and American, British, and Dutch interests in Southeast Asia. Kurusu had been sent from Tokyo to communicate to the Roosevelt administration his nation’s last best offer for peace in the region.

![]()

Right: Led by a Japanese officer, Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival walks under a flag of truce to negotiate the capitulation of British Commonwealth forces in Singapore, February 15, 1942. The siege and the ignominious surrender of Singapore, Britain’s “Gibraltar of the Orient,” to a much smaller Japanese force (36,000) was the greatest defeat in British military history. Over 80,000 British, Australian, and Indian troops fell into Japanese hands. Imprisonment, torture, illness, and many, many deaths awaited the captured ones.

|  |

Left: The Japanese occupation of Hong Kong began on December 25, 1941 (locally known as “Black Christmas”), after 2½ weeks of fierce fighting against overwhelming Japanese forces that had invaded the British Crown colony. Hong Kong’s surrender initiated almost four years of brutal Japanese administration. Some 7,000 British, Canadian, and Indian soldiers and civilians were kept in prisoner-of-war or internment camps, where famine, malnourishment, and sickness were pervasive. In this photo Japanese soldiers escort British, American, and Dutch bankers to detention in a small Chinese hotel; some bankers were executed as enemies of Japan. The Japanese government sold the Hong Kong dollar to help finance its wartime economy.

![]()

Right: Japanese troops advance through the streets of Malaya’s capital, Kuala Lumpur. The Malayan Campaign lasted from December 8, 1941, to January 31, 1942. For the British, Indian, Australian, and Malayan forces defending the colony, the campaign was a total disaster: 40,000 men were captured, 5,500 killed, and 5,000 wounded. On the last day of January the last organized Allied forces left Malaya for Singapore, which the Japanese invaded on February 7, 1942. The Japanese completed their conquest of the island on February 15, capturing 80,000 more prisoners out of 85,000 Allied defenders.

Color Documentary of Asia Pacific War, 1937–1945, Using Contemporary Japanese and American Films

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click