MULBERRY ARTIFICIAL HARBORS GET GO-AHEAD

London, England • September 4, 1943

On this date in 1943 the British War Office and Admiralty gave the go-ahead to build two temporary portable deep-water artificial harbors, one (codenamed Mulberry “A”) to be positioned off Omaha Beach at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer and the second (Mulberry “B”) off Gold Beach at Arromanches-les-Bains. The components of both harbors were to be prefabricated in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland by upwards of 200,000 laborers inside 8 months Then everything was to be towed by more than 100 tugs across the treacherous English Channel to their destinations a half mile/0.8 km off the French Normandy coast, the site of D‑Day, the invasion of German-occupied Northwestern Europe. Operation Overlord, the codename for the upcoming Allied liberation of Normandy and ultimately the whole of France and Western Europe, was sorely in need of a harbor or two for offloading assault troops, military equipment, precious ancillary matériel (e.g., fuel, ammunition, food, and medicine), and reinforcements that would sustain the invasion’s momentum. The ill-fated Anglo-Canadian Dieppe Raid (Operation Jubilee) the previous August demonstrated to the Allies that liberating the continent by attempting to seize a defended French port (Dieppe, Cherbourg, Le Havre, Dunkirk, or Calais) was at best a fool’s errand.

The building of these 2 mammoth secret weapons—Mulberry Harbor “A” and “B”—was a technical and logistical marvel at the time. It came at a mind-blowing cost: 25 million British pounds in 1944 (worth well over $1.43 billion in 2025). Built of reinforced concrete, the floating harbor piers, or landing wharves (codenamed “Spuds”), were connected to the invasion beaches by a string of 80‑ft./24‑m-long floating bridges (“Whales”) weighing 56 tons each that were attached to floating pontoons (“Beetles”). These concrete-and-steel structures were designed to adjust to Normandy’s tides that rose and fell 21 ft./6.4 m twice a day.

Besides piers and roadways, the harbors required breakwaters. Breakwaters comprised floating breakwaters (“Bombardons”), next to which huge, hollow concrete caissons (“Phoenixes”) were deposited on the sea floor. The largest type of Phoenix caisson (there were 6 of these monsters in all) was 200 ft./61 m long, 60 ft./18 m high, and weighed in excess of 6,000 tons. More than 213 “Phoenix” caissons of all types of were built. The final harbor requirement was a series of derelict vessels, or blockships (“Corncobs”), that could steam or be towed across the Channel to be scuttled stem to stern, thereby adding a third ring of protection against high waves and meddlesome currents. Gaps in the line of these 70 “Gooseberries” (sunken ships) allowed supply ships to enter and exit the protected anchorage.

On the afternoon of D‑Day, June 6, 1944, over 400 towed component parts (weighing approximately 1.5 million tons) set forth to create the cargo-handling harbors. They included the blockships to create the outer breakwater and the Phoenix caissons. At Arromanches the first Phoenix was sunk at dawn on June 8, 1944. By June 15 a further 115 had been sunk to create a five‑mile/8‑km-long protective arc off Gold Beach. The first Phoenix off Omaha Beach was sunk on June 9 and the Gooseberry breakwater was finished on June 11.

Both harbors were almost fully functional when on June 19 a large northeast storm at Force 6 to 8 blew into Normandy and devastated the Mulberry harbor at Omaha Beach. The Mulberries had been designed with summer weather conditions in mind, but this was the worst storm to hit the Normandy coast in 40 years. The destruction at Omaha was so severe that the entire harbor was deemed irreparable. Twenty-one of the 28 Phoenix caissons were totally destroyed. The harbor at Arromanches was more protected, and although damaged by the storm it remained intact. It came to be known as Port Winston after British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Port Winston saw heavy use for 8 months, despite being designed to last only 3 months. In the 10 months after D‑Day, it was used to land over 2.5 million men, 500,000 vehicles, and 4 million tons of supplies, providing much needed men and matériel to France as Allied armies sprinted east toward the German border. The captured Belgian port of Antwerp in September eliminated the need to maintain Port Winston.

Operation Overlord’s Secret Weapon: Mulberry Artificial Harbors

|  |

Left: Forming a 2‑mile/3.2‑km-long breakwater at Arromanches, part of Mulberry “B” harbor at Gold Beach, is a line of reinforced concrete Phoenix caissons (with displacements of approximately 2,000 tons to 6,000 tons each) being moved into position by tugs on June 12, 1944. Seacocks were opened to allow water to sink the hollow caissons—each as much as 6 stories tall and as long as a city block—into position. Antiaircraft guns were mounted on the largest caissons and barrage balloons floated overhead as protection against enemy aircraft. The Phoenixes formed the Mulberry harbor breakwaters together with the Gooseberries (scuttled or block ships), whose superstructures remained above sea level. Gooseberries were also placed off the other 3 Normandy assault beaches.

![]()

Right: Seven floating pier heads or landing wharves (Spuds) were connected by bridges. Each wharf could simultaneously berth 2 amphibious vessels such as LSTs (Landing Ships, Tank) or LCVPs (Landing Crafts, Vehicle, Personnel, commonly known as Higgins boats) or one 26 ft./8 m draft, 7,198‑ton Liberty ship with its heavy and bulky cargo. Looking like chimneys, 4 square towers pierced each corner of the 7 floating wharves to anchor the structures to the seabed. Unfortunately, the U.S. Navy Civil Engineer Corps did not securely anchor Mulberry “A” to the ocean floor as did their British counterparts, the Corps of Royal Engineers, at Arromanches (Mulberry “B”). During the violent Channel storms of late June 1944 Mulberry “A” incurred damage so severe that it was considered irreparable and further assembly ceased. Though the Omaha harbor was abandoned in late June, the sandy beach itself continued to be used for disembarking troops, vehicles, and stores and evacuating the wounded utilizing LSTs and similar craft. Using this method, the Americans were able to unload a higher tonnage of cargo than the British at Arromanches. Salvageable parts of the Omaha artificial harbor were sent to Arromanches to repair the Mulberry there.

|  |

Left: A U.S. Army truck traverses a Whale floating roadway leading from a Spud pier at Mulberry “A” off Omaha Beach. The British Admiralty’s Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development played an instrumental role in developing parts of the 2 artificial Mulberry harbors used in the D‑Day landings. By June 9, 1944, just 3 days after D‑Day, Mulberry “A” and “B” harbors were under construction at Omaha and Gold beaches, the American and British invasion beaches, respectively. Within the first 2 weeks of D‑Day, 20 fighting divisions and more than a million men were ashore.

![]()

Right: Black American soldiers construct a landing ramp at the end of a Whale floating roadway as part of Mulberry “A” at Omaha Beach. The ramp was steel mesh laid over wooden staves.

|  |

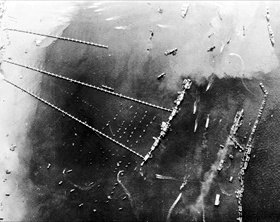

Left: An aerial view of Mulberry “B” harbor. Built of 2 million tons of steel and concrete, each Mulberry enclosed an area the size of England’s Dover harbor, or 2 sq. miles/5.2 sq. km. Once inside the Mulberry’s breakwaters (lower right in photo), ships and barges would anchor at a Spud pier head to discharge their cargoes. Pier heads were held on the seabed by 4 steel legs. The stout legs were built so that the piers could be raised and lowered in relation to the tide with the assistance of hydraulic jacks. The piers were directly connected to the shore by articulating 80‑ft./24‑m pontoon-mounted bridge spans (Whales) totaling 3,000 ft./914 m in length as shown in the left half of the photo. After the war many of Arromanches’ bridge spans were used to repair bombed bridges in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Some spans were used to build 2 bridges in Cameroon.

![]()

Right: Wrecked Mulberry “A” floating roadway, the result of a huge 3‑day gale, the worst in 40 years, on June 19–22, 1944. The gale broke the backs of 2 Gooseberry blockships. The floating outer breakwaters (Bombardons), though moored to the seabed, had been tied together by hemp rope. Some of the Bombardons broke up and sank while others broke free of their inferior moorings to collide with the blockships, concrete caissons, and floating piers and roadways, possibly causing more damage to the 2 sheltered harbors than the storm itself. On June 23, after the gale had blown itself out, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of U.S. First Army at Utah and Omaha beaches, strolled the beachfront, wincing at the damage: “I was appalled by the desolation, for it vastly exceeded that on D‑Day.”

Mulberry Artificial Harbors: D-Day’s Temporary Floating Harbors

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click