MOSCOW BOLSTERS DEFENSES AGAINST GERMAN SIEGE

Moscow, Soviet Union · October 19, 1941

On this date in 1941, the day the official “state of siege” was declared in the Soviet capital of Moscow, Red Army forces from the Soviet Far East and Siberia began arriving on the Russian Front. Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin was convinced that evacuating most of his troops from the Soviet-Japanese border represented little risk owing to information from a Tokyo-based spy, Richard Sorge. The Russian-born Sorge, whose cover was that of a Nazi reporter for the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine among others, was the Soviet informant who had correctly predicted the date of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union four months earlier (Operation Barbarossa) and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. To his everlasting discredit, Stalin stubbornly refused to believe reports from Sorge and other sources foretelling the approximate date of Adolf Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union, possibly because he believed them to be a ploy to disrupt the German-Soviet nonaggression pact of August 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Code-named “Ramsay,” Sorge (1895–1944) was one of the best Soviet intelligence officers of World War II, and he continued to feed Moscow information from his base in Tokyo until arrested by the Japanese secret police (Kempeitai, equivalent to the German Gestapo) on October 18, 1941. Until his confession under torture, Sorge was assumed by the Japanese to be a German spy. (The Soviets did not officially acknowledge Sorge was on their payroll until 1964.) Sorge was hanged on November 7, 1944, in Sugamo Prison outside Tokyo. After the war Sugamo Prison was the execution site of seven Japanese war criminals sentenced to death by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, among them Gen. Hideki Tōjō, Japan’s prime minister during most of World War II (1941–1944).

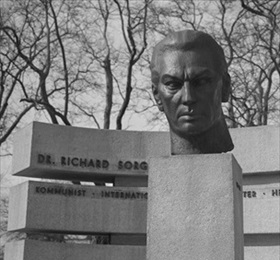

Sorge’s seminal role in the Battle of Moscow (October 2, 1941, to January 7, 1942) and perhaps in the Battle of Stalingrad (September 1942 to February 1943), during which the Germans suffered strategic defeats on their Eastern Front, is today memorialized in a roadside monument between Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport and the Kremlin. The former Soviet satellite in Eastern Germany, the German Democratic Republic, established a memorial garden named for Sorge in Dresden’s Altstadt (Old City) in 1970.

Spymaster Richard Sorge: Soviet Eyes and Ears in Prewar Japan

|  |

Left: Family photograph of Richard Sorge from 1940. Sorge was born in 1895 near Baku, Azerbaijan (then part of Russia), to a German mining engineer and a Russian mother. Back in Berlin where he grew up, Sorge served in the German Army during World War I (he was severely wounded), earned a PhD in political science, and joined the German Communist Party in 1919. His political views led him to leave Germany for the Soviet Union, where he became a junior agent in Moscow for the Comintern, an international communist organization. In 1929 Sorge was recruited by the head of Soviet military intelligence and worked for that department for the rest of his life. In May 1933 the department asked Sorge to organize a spy network in Japan, the same year Sorge “joined” the Nazi Party.

![]()

Right: A memorial plaque between Moscow and Sheremetyevo International Airport reminds passersby of Sorge’s contributions as a Soviet intelligence operative in Japan and China (Shanghai), where he collected information about Japanese and German plans in the lead-up to World War II. Many streets in Russia are named after Sorge. British spy and James Bond author Ian Fleming called Sorge “the man whom I regard as the most formidable spy in history.” Tom Clancy, American author of numerous spy novels, called Sorge “the best spy of all time.”

|  |

Above: In 1970 the Communist government of East Germany accorded the half-German, half-Russian anti-fascist hero with an impressive memorial garden in Dresden. First in the list of attributions under Sorge’s name (right photo) is the word “Kommunist.” Neither the memorial garden nor the adjacent street named after Sorge exists any longer after German reunification in 1990.

Battle of Moscow, October 1941 to January 1942, Germany’s First Defeat (You may want to mute the sound)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click