MONTE CASSINO ABBEY ORDERED DESTROYED

Cassino, Italy • February 15, 1944

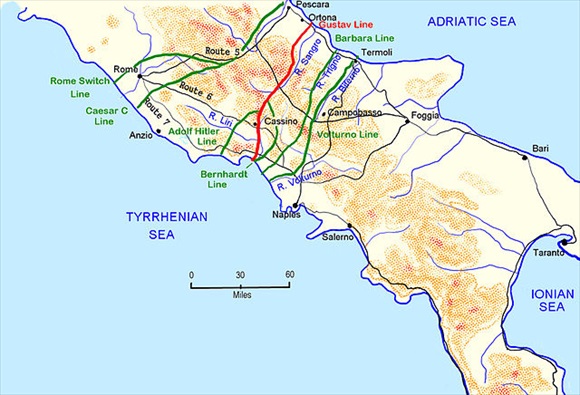

On this date in 1944 British Gen. Sir Harold Alexander, the highly decorated commander in chief of all Allied forces in the Mediterranean Theater, ordered the aerial bombing of the historic Benedictine abbey towering majestically over the town of Cassino on the banks of the Rapido (Gari) River in Italy. Earlier in January British, American, and French troops had made a series of attacks on the main German defenses in mainland Italy, the Gustav Line—this around the town of Cassino (red line on map below), approximately 20 miles/32 kilometers inland from Italy’s west coast. Sometimes called the First Battle of Cassino, these attacks produced only limited gains, which “disheartened” the tens of thousands of sick and battle-weary soldiers who had fought, suffered, and lost 11,000 of their own the previous month in the shadow of the fortress-like abbey. The costly loss of 11,000 men to countless German mines and booby traps, well dug-in tanks and trenches dug by conscripted labor, and withering near pinpoint accurate artillery and mortar fire didn’t include the 16,000 casualties in the 14 nightmare weeks and 50 miles/80 kilometers that Alexander’s warriors required to arrive at Cassino town from Naples in the first place!

The bombing of the iconic abbey, which Alexander and his men wrongly claimed was being used by the Germans as an observation post from which to direct deadly artillery fire below (the Germans vociferously contested the claim), was part of a broader effort by soldiers from 10 Allied nations and territories to break through the German lines and open 1 of only 2 uninterrupted roads connecting Southern Italy, in Allied hands, and German-held Rome, Italy’s capital. Monte Cassino’s destruction, Alexander admitted later, was “necessary more for the effect it would have on the morale of the attackers than for purely material reasons.” Indeed, as news of the pending air raid on the abbey circulated, it occasioned a “holiday atmosphere” as soldiers, generals, and news reporters scrambled for positions from which to watch what was to come. A group of doctors and nurses from a military hospital in Naples brought a picnic of K‑rations and settled themselves on nearby Monte Trocchio to enjoy the show, which ran 4 hours and included artillery shelling, all of which produced flames and columns of smoke that blotted out the sun.

Surprisingly, a day and a half passed before the initial air strike by 229 heavy and medium bombers, dropping 1,150 tons of high explosives and incendiary bombs on the ancient monastery, leaving it smoking rubble, was followed up by a renewed (and failed) ground attack by a single company. By then the Germans had plenty of time to scramble from their observation and defensive positions 200 yards/183 meters from the craggy hilltop and convert the ruins and the thick-walled foundations of the seven-acre abbey into an even more impregnable stronghold from which they could direct murderous artillery fire against anyone sent against them.

More air and ground assaults would take place before the Allies, after suffering approximately 55,000 casualties (the Germans incurred at least 20,000 casualties, civilians a tenth of that), were able to raise their flag—an improvised Polish regimental flag—over the rubble of the abbey on May 18, 1944, as well as over 30 wounded soldiers left by their comrades as the Germans abandoned the western half of the Gustav Line for new defensive positions along the Adolf Hitler Line (green line on map). Monte Cassino’s capture proved to be the breaking point of German defenses along the Gustav Line as well as the momentum behind the liberation of all but the remaining third of German-occupied Italy. However, the utter decimation of a religious and culturally significant icon over a four-month period forever remains a highly controversial wartime decision.

The Historic Hilltop Abbey of Monte Cassino, Founded in AD 529 by St. Benedict of Nursia

|

Above: This map depicts the extensive series of fortified defensive lines from the Tyrrhenian Sea in the southwest to the Adriatic Sea in the northeast that stretched across the Italian peninsula south of Rome, 1943–1944. Carefully prepared and positioned, the lines marked the frontier between German-occupied Italy to the north and Allied-occupied Italy to the south. The primary line, centered on the town of Cassino, was the Gustav Line (red line on map). The line leveraged the heights of the Apennine Mountains, afforded its defenders natural strongholds and ample overlapping fields of fire, and restricted north-south vehicular traffic to several valleys. Perched on Monastery Hill above the small western Italian town of Cassino was the medieval Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino, today usually spelled as one word, Montecassino. Together the hill and abbey dominated the entrance to the Liri River Valley, one of two western approaches to Rome roughly 90 miles/145 kilometers due north. Adolf Hitler had ordered the Gustav Line defended “in a spirit of holy hatred not only against the enemy, but against all officers and units who fail in this decisive hour.”

|  |

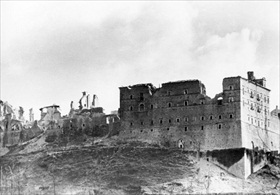

Left: Ruins of the town of Cassino after the hellish 4‑month battle. In the background are the ruins of the 4‑stories-tall Abbey of Monte Cassino atop Monastery Hill. The abbey lay just over 1 mile/1.6 kilometers to the west of the town at an elevation of 1,700 feet/518 meters and had a commanding view of the Liri and Rapido valleys, Allied gateways to German-held Rome. The battles to take the town and iconic abbey cost the lives of more than 14,000 men from a dozen nations. Total Allied casualties spanning the period of the 4 Cassino battles and the Anzio campaign with the subsequent capture of Rome on June 5, 1944, were over 105,000. Although the Allies’ drive to Rome was excessively bloody and all-consuming, the Italian capital, paradoxically, was an open city of no strategic value.

![]()

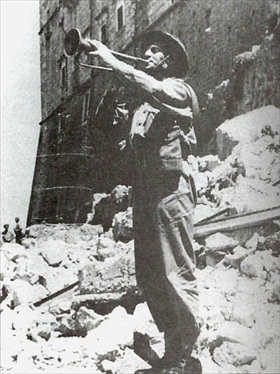

Right: A Polish bugler proudly plays the traditional 5‑note Polish anthem, the Hejnał Mariacki (also called the Kraków Anthem), at the foot of Monte Cassino Abbey, announcing the Allied victory on May 18, 1944. Elements of the battered Polish II Corps were the first among the Allied units to reach Monte Cassino’s summit.

|  |

Left: Abbey of Monte Cassino in ruins, February 1944, following Operation Avenger, the first of two aerial bombardments of the hilltop monastery. (A second bombing occurred on March 15.) St. Benedict of Nursia established his first monastery, the source of the Benedictine Order, here around AD 529 and over time it become a repository of valuable art works and a world-renowned library. The controversial and tragic destruction of the abbey, fortunately empty of its movable art and library collections, and the death of as many as 250 Italian civilian refugees who had sought sanctuary within its walls were an immediate propaganda coup for the Nazis. Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels played up the Allies’ “senseless lust of destruction” and deaths for all their worth. A spokesperson for Pope Pius XII branded the bombing “a colossal blunder . . . a piece of a gross stupidity.” Within time the U.S. Army reached the same conclusion: the bombing had “gained nothing beyond destruction, indignation, sorrow and regret.”

![]()

Right: The restored Abbey of Monte Cassino balances atop Monastery Hill, a rocky outcrop some 90 miles/145 kilometers southeast of Rome. Reconstruction of the abbey began in 1950, and in 1964 the new structure was reconsecrated by Pope Paul VI. Monte Cassino is still one of the most famous monasteries in Christendom.

The Allies’ Gethsemane: The Hellish Battle for Monte Cassino, Italy, January–May 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click