MILITIA FORMED TO DEFEND JAPANESE HOMELAND

Tokyo, Japan · March 24, 1945

On this date in 1945 the Japanese Deputy Minister of War, Lt. Gen. Kaneshiro Shibayama, informed the Japanese Diet (Parliament) of the formation of a militia for the defense of the Home Islands. A home militia was critical to the nation’s survival because 60 percent of the roughly 4.6 million Japanese combat troops were still stationed aboard.

The next month, on April 8, the operational plan to defend the homeland, called Ketsu‑Go (“Decisive Operation”), was issued. As a result of lessons learned in the South Pacific, the intent of Ketsu‑Go was to inflict enormous casualties on the invaders. In fact, this strategy had been tested most recently on the island of Iwo Jima in February and March 1945, where one in three U.S. Marines had been killed or wounded. Japanese tenacity in combat would, it was believed, undermine the American public’s will to continue the fight for Japan’s unconditional surrender; instead, the American public would insist on a peace more advantageous to Japan than otherwise if for no other reason than to push the past four years of slaughter and misery out of their minds and bring “the boys” home.

Preparations for Ketsu‑Go were to be conducted in three phases. The first phase, during which defensive preparations and combat unit organization were completed, continued through July 1945. (Combat unit organization involved activating the First and Second General Armies, the latter army headquartered in Hiroshima, as well as an Air General Army, which had at its disposal close to 13,000 aircraft, almost all of which were converted into one-way suicide planes.) The second and third phases of this all-out joint defense effort were to have ended in October, when Japanese military officials forecast an American invasion of the Home Islands might begin.

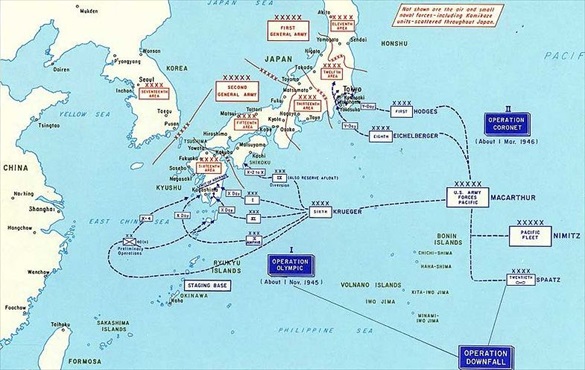

The latter two phases were never completed because the Americans had their own plan for undermining the enemy’s will to continue fighting—all this without any further high-cost air, sea, and ground operations envisioned in Operation Downfall (see map and description below) and without any direct or behind-the-scenes diplomatic negotiations that might end with less than unconditional Japanese surrender. The American plan was awesome and dramatic and centered on using a new weapon, the atomic bomb, two of which blasted, seared, and irradiated tens of thousands of combatants and noncombatants alike residing in Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, respectively. The way America decisively ended the war against Japan remains one of the great controversies in U.S. and Japanese history.

Defending the Japanese Homeland Against the Planned U.S. Invasion, 1945–1946

|

Above: This map outlines the Japanese and U.S. ground forces scheduled to take part in Operation Downfall, the battle for Japan. Two landings were planned: Operation Olympic, on the southern island, Kyūshū, set to begin around November 1, 1945, and Operation Coronet, on the main island, Honshū, set to begin the following spring. The War Department staff in Washington estimated there would be 250,000–800,000 fatalities in an invasion of Japan—of which 5,000 casualties would occur at sea from kamikaze strikes, per the U.S. Navy—and 5 to 10 million Japanese fatalities. American casualties were estimated to range between 1.7 and 4 million. The key assumption was large-scale participation by civilian militias in the defense of the Home Islands if the battle shifted to inland guerrilla warfare. Operation Downfall was abandoned when Japan formally surrendered on September 2, 1945, after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki the previous month. The half-million Purple Hearts produced in preparation for invading Japan were not needed.

|  |

Left: Female students receive training in gun handling as members of a volunteer fighting corps, or Kokumin Giyū Sentōtai, in Tokorozawa, now considered a suburb of Tokyo. Governors of prefectures (states) could conscript all male civilians between the ages of 15 and 60 years, and unmarried females between 17 and 40. Commanders were appointed from retired military personnel and civilians with weapons experience. The Kokumin Giyū Sentōtai was intended as the main reserve, along with a “second defense line,” for Japanese forces to sustain a war of attrition against invading forces. After the Allied invasion, these forces were intended to form resistance or guerrilla warfare cells in cities, towns, and mountains. At this stage of the war, most militia members were armed with swords, sickles, knives, fire hooks, and even bamboo spears due to the lack of modern weaponry and ammunition.

![]()

Right: Student militia at Kujukurihama, Chiba, a prefecture situated east of Tokyo across Tokyo Bay. Some 28 million men and women were considered “combat capable” by the end of June 1945; yet only about 2 million were recruited when the war ended, and most of these never experienced combat owing to Japan’s surrender before the Allied invasion of the Japanese Home Islands could proceed.

Newsreel Documenting Japan’s Unconditional Surrender on Board the USS Missouri, September 2, 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click