MANZANAR IS MODEL FOR 10 U.S. JAPANESE INCARCERATION SITES

Manzanar, Owens Valley, Inyo County, California • February 27, 1942

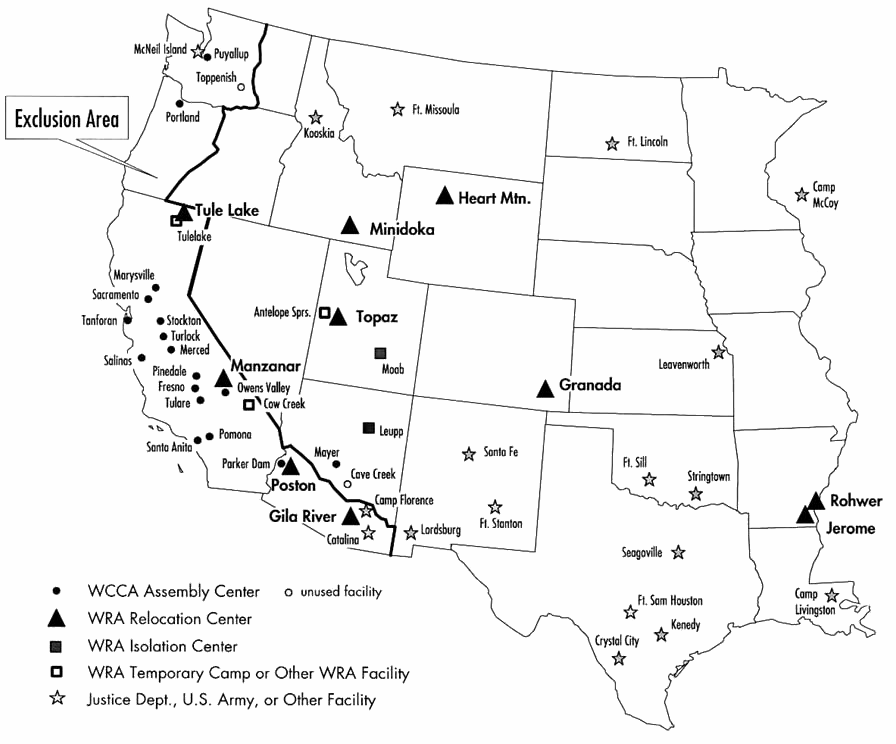

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order empowered the U.S. Army’s recently established Western Defense Command to designate areas on the Pacific Coast of the United States from which “any and all persons may be excluded” in the interests of national security. The language of 9066 was neutral as to those potentially affected by the order. But in light of the U.S. declaration of war against the Empire of Japan 2 months earlier it wasn’t hard to guess that Roosevelt’s order chiefly targeted persons of Japanese descent for exclusion. Huge swathes of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona, and all California, collectively forming Military Areas No. 1 and 2, were declared “theaters of war” (see map below). In these 4 states lived 75,000 Japanese American citizens (Nisei and Sansei in Japanese) and 45,000 Japanese immigrants (Issei), or nationals, the latter ineligible for U.S. citizenship on the basis of race. California alone was home to 94,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry. Starting February 2, 1942, Japanese nationals were required to register with the U.S. Department of Justice’s FBI as “enemy aliens.”On this date, February 27, 1942, specialists from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers out of Los Angeles appeared in California’s Owens Valley, which lies in the remote, extreme east of the state. They and a smattering of locals selected the former town site of Manzanar (Spanish for “apple orchard”; again, see map) as the location of the first “processing center” of people relocated from the U.S. West Coast against their will and without due process. Thus, the sleepy abandoned fruit orchards were transformed into an incarceration site for over 10,000 people of Japanese ethnicity, becoming the model for 9 successor incarceration sites that spread across the western half of the U.S.

From the start the Army Corps of Engineers, the War Department, and the head of the Western Defense Command, 62‑year-old Gen. John L. DeWitt, all conceived the Manzanar site to be “temporary housing.” West Coast Japanese Americans and nationals would be rounded up, delivered to and detained in makeshift assembly centers (which Manzanar initially was), and then quickly relocated east of Military Areas No. 1 and 2 (with 4 exceptions it turned out) or east of the Mississippi River if states there would accept the evacuees. The Corps completed the design of the incarceration site in 5 days. Manzanar’s residential site plan resembled other military camps the Corps had designed for young, healthy servicemembers: in this instance, 36 blocks of black tarpaper-covered wooden barracks laid out in 2 columns of 8 rows each, with communal dining halls, showers, and latrine/laundry facilities in separate buildings. Construction was budgeted at $5 million.

Initial construction of the Owens Valley Reception Center (OVRC) began on March 14, 1942. A week later the first West Coast Japanese to be evacuated arrived. Managing their removal and delivery to Manzanar’s OVRC was the responsibility of the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), an agency of the Western Defense Command established 3 days earlier. The men and women of WCCA were mostly drawn from Roosevelt’s Works Project Administration (WPA), which had been in existence since 1935. After June 1, 1942, responsibility for administrating OVRC was transferred to the new War Relocation Authority (WRA), a U.S. civilian agency, and the Manzanar site renamed Manzanar War Relocation Center (MWRC). As time went on the WRA on-site staff numbered up to 229, of which 20 were WCCA holdovers.

The Manzanar incarceration site covered approximately 540 acres/220 hectares. Eight guard towers manned by military police were located at intervals around the 5 foot/1.5 meter, 5‑strand‑high barbed wire perimeter fence. The residential area was about 1 square mile/2.6 square kilometers and consisted of a grid of 36 identical, hastily constructed blocks of 13 20‑by‑100‑foot/6.1‑by‑30‑meter‑long tarpaper-covered wooden residential barracks, with each family (up to 6 members, down from 8) squeezed into 1 of 4 tiny 20‑by‑25‑foot/6.1‑by‑7.6‑meter primitive “apartments” lit by a single light bulb and heated by an oil-burning stove. Uprooted from their West Coast homes, neighborhoods, farms, and sites of employment, worship, and learning supposedly for a limited duration, U.S. residents of Japanese heritage were forced to live out World War II in remote and unfamiliar places.

Manzanar War Relocation Center for West Coast Residents of Japanese Ancestry, 1942–1945

|

Above: Map showing (a) the massive World War II exclusion area (Military Areas 1 and 2) and (b) sites of involuntary confinement in the continental U.S. for over 120,000 Japanese nationals (“alien enemies”) and Japanese American citizens (labeled “non-alien enemies”) who resided in 4 Western states as well as for over 31,000 suspected enemy nationals and their families interned under the Enemy Alien Control Program. The 10 hastily built confinement sites, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” are identified by black triangles. The sites were located in 7 states all west of the Mississippi River and cost the government $40 million annually to operate. All relocation centers were built in out-of-the-way places, many in desolate high deserts or swamp land. Identified by stars are facilities administered by the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Army. It was to these often former Civilian Conservation Corps camps that Japanese arrested between December 8, 1941, and early 1942 were exiled indefinitely—that is, before Executive Order 9066 was in place. Indeed, the full extent of wartime incarceration includes thousands of German and Italian nationals living in the U.S. or deported from Central and South America, plus forcibly relocated Alaskan natives, Japanese Latin Americans, and some Japanese Hawaiians. These unfortunate people, along with Japanese nationals and American-born Japanese, were incarcerated in more than 59 U.S. government facilities. In the map legend WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration and WRA = War Relocation Authority, successor to WCCA.

|  |

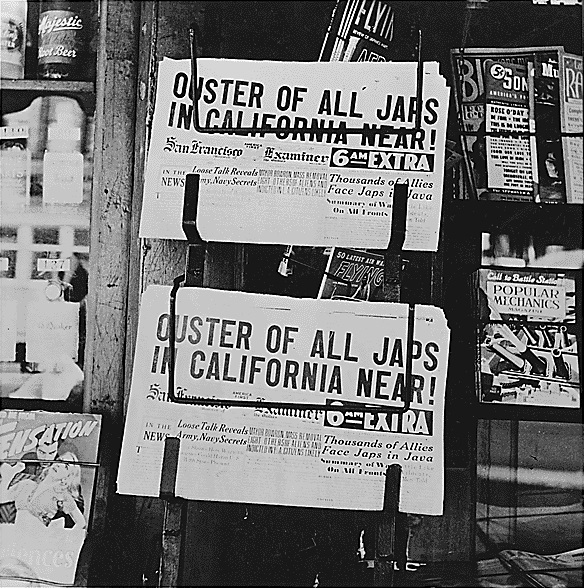

Left: Anger over Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, invasion jitters, and race prejudice swept over scared West Coast residents, who largely wanted all Japanese descendants out of their area as quickly as humanly possible. “OUSTER OF ALL JAPS IN CALIFORNIA NEAR!” screams San Francisco Examiner headlines of Japanese relocation, February 27, 1942. On May 21, 1942, the rival and equally hostile San Francisco Chronicle told its readers: “S.F. Clear of All But 6 Sick Japs. . . . The last group, 274 of them, were moved yesterday.” Photo by Dorothea Lange. Lange was 1 of 3 photographers in the WRA Photography Section, or WRAPS, in 1942–1943. The other 2 were Clem Albers and Francis Stewart. A civilian, the photographer Ansel Adams made 4 trips to Manzanar between 1943 and 1944, documenting camp life in a less than ideal setting. Toyo Miyatake, a professional photographer before his incarceration in Manzanar, had the camp director’s permission to also shoot pictures of camp life.![]()

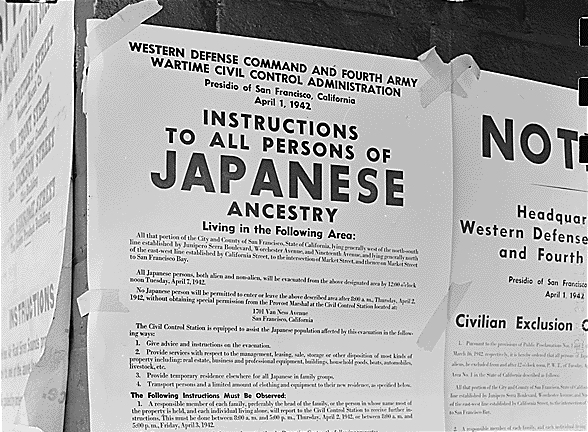

Right: The official notice of exclusion and forcible removal, April 1, 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange. Per the posted exclusion order, all Japanese Americans living in the first San Francisco section were directed to evacuate the Pacific Coast en masse, a violation of their civil liberties as U.S.‑born citizens. Years before the December 7, 1941, Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the U.S. government had drafted plans to intern some Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals (Issei) and had already placed some coastal communities under surveillance. This despite many years’ worth of FBI and naval intelligence data that attested to residents of Japanese origin posing no national security threat. The exclusion order also swept up Japanese American soldiers who had taken an oath of allegiance to their country of birth.

|  |

Left: With luggage tags affixed to their clothing—an aid in keeping family units intact during all phases of their forced removal—members of the Moriji Mochida family await an evacuation bus in Hayward, Alameda County (San Francisco Bay area), California, May 8, 1942. On the luggage tags was written the family’s designated identification number. Mochida’s youngest child was 3. The Mochidas had operated a 2‑acre/0.8‑hectare nursery and 5 greenhouses in San Leandro, Alameda County, before their incarceration. Photograph by Dorothea Lange.![]()

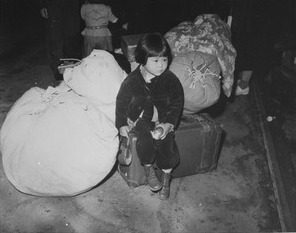

Right: The forced exodus of Japanese in Los Angeles started at the end of March 1942. Staring into uncertainty 2‑year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa, clutching a tiny purse and an apple with a few bites gone, waits with the family’s allotment of baggage before leaving a chaotic scene at Los Angeles’s Union Station. The child and her single mother Mikiko Hayakawa arrived in late March or April 1942, like most Japanese Angeleno evacuees, at Manzanar War Relocation Center, more than 200 miles/322 kilometers north of LA in California’s Owens Valley, which would be their home for the next 3½ years. Each displaced family member was permitted to take bedding and linens (no mattresses), toilet articles, extra clothing, and “essential personal effects,” nothing more; in other words, only what could be carried. Photograph by Clement “Clem” Albers.

|  |

Left: On March 17, 1942, construction began at the Manzanar War Relocation Center site for evacuees of Japanese ancestry in California’s Owens Valley, flanked by the High Sierras and Mt. Williamson. Photo by Clem Albers. Manzanar was an internment camp built from scratch primarily by camp residents. Some 764 tarpaper-covered wooded structures were completed within 3 months by a crew of 600 unskilled men drawn from Southern California working 10‑hour days, 6 days a week, and rolling out 2 barracks an hour. Due to a critical housing shortage in the Owens Valley, WRA staff—nearly 100 employees at the start—and their families should they be married lived cheek by jowl with camp residents in blocks of highly flammable barracks until staff housing with indoor plumbing, a 1‑person kitchen, living room, and bathroom could be built during Phase II–IV by Japanese craftsmen. The first West Coast Japanese arrived on March 21, 5 days after construction began. The arrivals initially sheltered in tents just like outside construction workers and WRA staff did. On April 28 Manzanar’s Japanese population swelled to 7,101. More WRA staff and families arrived to bring the number of Caucasians to over 400. A total of 11,070 native-born Japanese (most over the age of 50) and Japanese Americans (86 percent 25 years or younger) were incarcerated at Manzanar without charge.![]()

Right: Barracks under construction. Because the War Department had no intention of housing residents at Manzanar at government expense until the end of the war (whenever that happened), it had no interest in building comfortable living quarters for short-term occupants. Photo by Clem Albers. Manzanar incarcerees—guinea pigs for the next 9 WRA incarceration camps—were forced to live in flimsy, cramped, and drab “apartments” made using green lumber and other low-grade materials. Barracks originally had no ceiling and no drywall on inside walls, eliminating any chance of privacy. Knot holes that fell out were covered over with tin can lids nailed to the walls and floors. Shiplap flooring with gaps between boards made it impossible to keep the pervasive dust out of the living quarters until evacuee craftsmen laid a linoleum-type material over the floorboards and hung drywall on ceilings and walls. Camp residents endured brutally cold winters, scorching summers, and fierce, dusty, and grit-laden ever-present wind.

|  |

Left: Underneath the exterior appearance of a prison camp, Manzanar’s incarcerees participated in many of the same activities people on the outsider enjoyed in a typical American setting. Children went to day care centers while older ones (some 2,700) attended fully accredited elementary, junior high, high school, and junior college, all of which afforded instruction for special needs students. Older folks attended adult education and business classes. A Children’s Village (orphanage) cared for over 100 boys and girls ages 6 months to 17 years. In time, a 250‑bed hospital staffed chiefly by incarcerees provided the best healthcare of any hospital within 200 miles/322 km. Hospital stay: $15 per day. Residents played 9‑hole golf on a dirt course, attended Buddhist temples (there were 3), Protestant and Catholic churches, were served by a Los Angeles-based Bank of America and a branch of the Los Angeles Post Office, read a mostly uncensored newspaper (Manzanar Free Press) written and printed by residents, attended an outdoor movie theater, played football, basketball, volleyball, and baseball as photographer Ansel Adams recorded in 1943, visited newly laid out parks and picnic areas, planted flower and vegetable gardens, held dances and Boy and Girl Scout troop meetings in their recreation halls, met each other at the 2 Ys, social, and martial arts clubs, took vocational training and dance classes, and patronized Manzanar’s barber and beauty shops, shoe repair shops, as well as cooperatives that sold drinks, food, and household supplies.![]()

Right: Forty-five percent of Manzanar’s adults were employed at the camp in a variety of jobs using skills, drive, and a work ethic they either brought with them or they learned there. Jobs included clothing and furniture manufacturing, farming and tending orchards, military manufacturing such as camouflage netting and experimental rubber from guayule plants, teaching, civil service jobs such as police, fire fighters, and nursing, and general service jobs operating stores, beauty parlors, and a bank. By the summer of 1943, camp orchards, gardens, and farms were producing apples, pears, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, eggplant, cucumbers, Chinese cabbage, watermelon, radishes, and peppers. Eventually, there were more than 400 acres of farms (see above photograph by Ansel Adams) producing more than 80 percent of the produce consumed at the camp. Chicken, hog, and cattle raising operations began in 1944. Camp employees were paid monthly. Unskilled workers earned $8.00 per month ($149.20 per month in 2024 dollars), semi-skilled workers earned $12 per month ($224 per month in 2024 dollars), skilled workers such as butchers made $16 per month ($298 per month in 2024 dollars), and professionals such as physicians, surgeons, and dentists earned an insulting $19 per month ($354 per month in 2024 dollars). Internees’ pay could not exceed the earnings of the lowest paid army recruit. In addition, everybody received $3.60 per month ($67 per month in 2024 dollars) as a clothing allowance.

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click