LEAFLETS WARN JAPAN POPULACE OF APOCALYPSE

509th Composite Group HQ, Tinian, Mariana Islands · August 8, 1945

On this date in 1945 in Japan, two days after 40,000 Hiroshima men, women, and children had died in an instant (90,000–166,000 would die within days of burns and radiation), U.S. airplanes carpet-bombed the country with over five million leaflets. The leaflets described Hiroshima’s utter devastation and warned residents of similar destruction across Japan until Tokyo agreed to the unconditional surrender terms spelled out in the Potsdam Declaration issued by the U.S., Great Britain, and China on July 26, 1945. In the nation’s capital the Japanese Supreme War Direction Council met to discuss the country’s options. Council members heard reports that 44 major cities had been largely destroyed. Toyama, over 400 miles north of Hiroshima in central Honshū, Japan’s main island, was the worst hit—99 percent destroyed when B‑29 Superfortresses dropped 1,466 tons of napalm on the city. Another 37 cities, including Tokyo, were over 30 percent destroyed. (Actually over 50 percent of the capital lay in ruins.) Eight million people were injured and without shelter, and civilian and military casualties approached two million. Despite the depressing reports, the Supreme War Direction Council could not come to a decision until the next day, when the diminutive, myopic Emperor Hirohito personally intervened and ruled out approaching the Soviet Union or neutral Sweden and Switzerland for better peace terms. On August 9, 1945, the day of Nagasaki’s destruction, the Japanese cabinet and the Supreme War Council voted to accept the Allies’ peace terms provided Hirohito’s prerogatives as emperor were preserved. The Allies worked out a face-saving compromise whereby Hirohito could stay on his throne “subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers,” Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Approved by President Harry S. Truman, the Japanese surrender documents were sent to MacArthur. Again U.S. aircraft took to Japanese skies, dropping millions more leaflets explaining the position reached in the surrender negotiations. On the same day that Hirohito was to broadcast Japan’s acceptance of the Allies’ terms, over one thousand soldiers stormed the Imperial Palace in an effort to prevent the recorded message from being broadcast. They were beaten back. On news of the surrender, the Allies prepared for the occupation of Japan.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1849083827,0141001461,1846032849,0760341222,0870134035,0199569762,0552778508,1416584404,184884753X,1594160392″ /]

Prodding Japan to V-J Day, or Victory Over Japan Day

|  |

Left: This leaflet was dropped on Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and 33 other Japanese cities on August 1, 1945. It shows B‑29s dropping incendiary bombs over Yokohama on May 29, 1945. The Japanese text on the reverse side of the leaflet carried the warning: “Read this carefully as it may save your life or the life of a relative or friend. In the next few days, some or all of the [12] cities named on the [front] side will be destroyed by American bombs. . . . We cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked [Hiroshima was not named on the front—ed.] but some or all of them will be, so heed this warning and evacuate these cities immediately.”

![]()

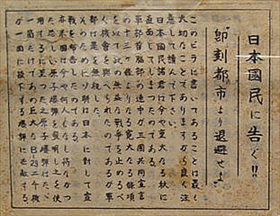

Right: A leaflet dropped from a B‑29 on Japan after the bombing of Hiroshima, which caused widespread panic in many Japanese cities. Translation: Notice to the Japanese People! Evacuate the city immediately. What this leaflet contains is extremely important, so please read carefully. The Japanese people are facing an extremely important autumn. Your military leaders were presented with thirteen articles for surrender [i.e., Potsdam Declaration] by our three-country alliance to put an end to this unprofitable war. This proposal was ignored by your army leaders. Because of this the Soviet Republic intervened. In addition, the United States has developed an atom bomb, which had not been done by any nation before. It has been determined to employ this frightening bomb. One atom bomb has the destructive power of 2000 B‑29s. This frightening fact should be understood by you by observing what kind of situation was caused when only one was dropped on Hiroshima. This leaflet caused widespread panic in many Japanese cities.

|  |

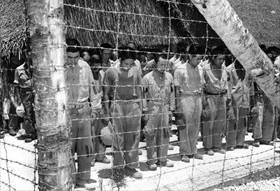

Left: U.S.-held Japanese POWs bow their heads after hearing Hirohito’s surrender announcement, Guam, August 15, 1945.

![]()

Right: Jubilant Americans declared August 14 “Victory over Japan Day,” or “V‑J Day.” Images from V‑J Day celebrations in New York’s Times Square (shown here) and around the U.S. reflected the overwhelming sense of relief and exhilaration Americans felt at the end of the bloody, 45-month conflict. In a nationwide broadcast from the White House on August 14 President Truman said: “This is the day we have been waiting for since Pearl Harbor. This is the day when Fascism finally dies, as we always knew it would.” Time zone differences determine whether V‑J Day is celebrated on August 14 or August 15, the date Hirohito broadcast his country’s capitulation. In Japan, August 15 usually is known as the “memorial day for the end of the war”; the official name for the day, however, is “the day for mourning of war dead and praying for peace.”

National Geographic Presentation: Hiroshima Nuclear Apocalypse, August 6, 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click