LAST HOLDOUTS SURRENDER TO JAPANESE

Manila, Occupied Philippines · May 6, 1942

On December 8, 1941, Japanese forces invaded the Philippines, a largely self-governing U.S. possession. (December 8, Manila and Japanese time, was the same date Japanese carrier-based planes attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in a set of interlocked assaults on U.S. military assets in the Pacific region.) The combined U.S.-Filipino force led by Gen. Douglas MacArthur could not check the Japanese advance and withdrew onto the Bataan peninsula, across the bay from the Philippine capital Manila, where they held out until April 1942. Nearly 80,000 U.S. and Filipino troops went into Japanese captivity, many of them murdered or dying from exhaustion, dehydration, exposure, and the brutal treatment by their captors on the subsequent four-day, 80‑mile “death march” out of Bataan to inland prison camps. The last-ditch U.S. stronghold, the tadpole-shaped “rock” of Corregidor in Manila Bay, finally surrendered its booty of 16,000 American and Filipino soldiers on this date in 1942. The drawn-out fight in the Philippines forced Japan to commit more troops than planned to capture an objective far less important to their ambitions of securing the great mineral resources of British Malaya, overwhelmed in mid-January 1942, and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), which surrendered on March 9, 1942. In the months preceding the outbreak of hostilities, Japanese expansionists and policymakers had counted on the anticipated successes of their early military operations in Southeast Asia to nudge the Western colonial powers to sue for peace after hostilities had broken out. When that didn’t happen, the sanguine appraisal of how Japan was going to win the Pacific war it had started morphed into anxiety and later despair. Fully 80 percent of Japanese troops remained tied down in a ground war in China that Japan had started in 1937. The rest of the army and the Imperial Japanese Navy now had to contend with a massive buildup of a revived U.S. Pacific fleet, as well as converging attacks by U.S. and British Commonwealth forces from one retaken Pacific island after another. In the end, the bushidō spirit (“warrior spirit”) that the Japanese fell back on as their fortunes turned bleaker by the month could not trump the Allies’ superior strength in armaments and fighting men, a combination that secured the Allies victory over Japan in September 1945.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0440236959,0743474503,1484162404,0425257738,0345449118,1439199655,0786441801,0786459387,1574888064,0815410859″ /]

The 80-Mile Bataan Death March Began on April 9, 1942

|  |

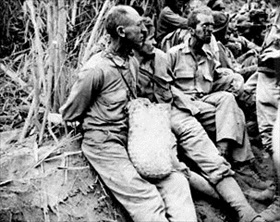

Left: American and Filipino troops surrender to Japanese invaders on Bataan. The three-month Battle of Bataan (January 7 to April 9, 1942) resulted in the largest surrender in American and Filipino military history, and was the largest U.S. surrender since the American Civil War.

![]()

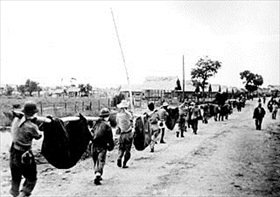

Right: Route taken during the Bataan Death March. Section from San Fernando to Capas was by rail, and from there to Camp O’Donnell 9 miles further by foot or truck. Another POW camp was located near Cabanatuan City, where as many as 8,000 American and other Allied POWs and civilians were imprisoned.

|  |

Left: U.S. soldiers, their hands tied behind their backs, rest on the Bataan Death March to their prison camp at Cabanatuan. Approximately 2,500–10,000 Filipino and 100–650 American prisoners of war died from thirst, wounds, disease, and their captors’ savage mistreatment, including executing stragglers, before they reached Camp O’Donnell.

![]()

Right: American and Filipino POWs, using improvised litters, carry the bodies of their comrades who died shortly after their arrival at Camp O’Donnell. Survivors of the march continued to die at a rate of 30–50 per day. Rosedith Van Hoorebeck Hawkins, a U.S. Army nurse with the Thirty-Fifth General Hospital, described the survivors of the camp’s liberation in 1945 this way: “The boys who’d been in the Bataan Death March came to us, and I’m telling you they were a mess. . . . They couldn’t eat so we just gave them liquids and soft foods. . . . Almost all of them had lost a foot or arm or leg. They’d had no medical treatment and had healed very badly.” (Quoted in Diane Burke Fessler, No Time for Fear: Voices of American Military Nurses in World War II.)

The Bataan Death March and Prisoner of War Camps

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click