KOKODA TRAIL SWEEP IS LEAD-UP TO CAPTURING BUNA-GONA

Port Moresby, New Guinea • November 2, 1942

After failing in the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942) to take the Australian administrative capital of Port Moresby on the island of New Guinea (see map), 4,400 Japanese troops landed on the island’s northeastern shore on the night of July 21/22, 1942, and established beachheads at (east to west) Buna, Sanananda, and Gona. From there they marched southwest over very difficult terrain following the Kokoda Trail (or Kokoda Track, which was really just a footpath) in an effort to take Port Moresby by land. Meeting the Japanese on the Kokoda Trail (highest elevation: 7,185 ft/2,190 m), the vastly outnumbered Australian and native Papuan forces fought a two-month defensive battle, being pushed down the jungle-clad Owen Stanley Mountain Range that ran diagonally across the peninsula back toward Port Moresby. Within 30 miles/48 km of the lights of the capital, the Japanese waited in vain for reinforcements. On September 18 the invaders’ commanding general, Gen. Tomitarō Horii, received orders to withdraw to his seaside Buna-Gona stronghold so that the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy could concentrate their resources on expelling Americans from Guadalcanal (August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943), an island in the Solomons chain 850 miles/1,368 km to the east. Withdrawal was just as well for by then 80 percent of his fighters had been wounded, killed, or disabled by tropical disease and rice rations had dwindled to nil.

Australian forces counterattacked the retreating enemy, capturing Kokoda and the settlement’s airfield for the final time on this date, November 2, 1942. Fighting a series of fierce battles against rearguard defenses on the narrow mountain track, the Australians reached heavily defended Japanese lines near the swampy or waterlogged Buna-Gona coastal perimeter, which stretched 15 miles/24 km. It was the beginning of the wet season, which brought tremendous rainfall along with oppressive humidity and a myriad of tropical illnesses, chiefly malaria.

On January 2, 1943, the Allies finally captured Buna, 6 weeks after Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Southwest Pacific Area commander, had given the order, on November 21, 1942, to “take Buna today at all costs.” By January 22, 1943, the Allies had indeed taken every enemy stronghold and killed (or rarely captured) every Japanese defender between Buna and Gona. Fanatical resistance by the enemy led the sick and wounded in Buna’s hospital to fight to the death or commit suicide. Only 50 Buna defenders, mostly garrison laborers, were captured, while an estimated 7,600 died.

In one sense the grueling Buna-Gona Campaign richly rewarded the U.S. and Australian officer corps. Innovations in jungle warfare, small-unit tactics, close-quarters combat, closely coordinated infantry-tank assaults, air-ground cooperation, air transport for troops and supplies, and communications were put into practice in later Pacific engagements, including those on the western (Dutch) half of New Guinea. But all that on-the-job learning cost the Allies dearly in terms of combat casualties (3,470 Australians and 2,605 Americans by one count), partly because MacArthur remained mostly ignorant of the complex tactical situation faced by his subordinate commanders, infantrymen, and airmen (MacArthur never once visited the front, staying instead in Port Moresby), and partly because the general, egged on by his reckless nature and persistent need to make haste, saw himself in personal competition with U.S. Marines and Adm. William Halsey’s Guadalcanal slugfest as to which of them would inflict the first major land defeat on the Japanese.

Beachhead Bloodbath: Buna, Sanananda, and Gona, Mid-November 1942 to Late January 1943

|

Above: Lying on the southeastern coast of the Papuan Peninsula, Port Moseby was the Australian administrative capital of the Territory of Papua. The Japanese objective during the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May 1942 was to turn the settlement into a staging point and major air base from which they could sever Australia, several hundred miles/kilometers to the south, from Southeast Asia and North America. In 1975 the Territory of Papua and the Australian-administered Territory of New Guinea on the northeastern shore of the peninsula (former German New Guinea before the outbreak of World War I) merged to become Papua New Guinea, with Port Moresby as the seat of the independent country.

|  |

Above: Australian Militia soldiers of the 39th Battalion following their relief at Kokoda village and airstrip, New Guinea, September 1942 (left image) and men of the 128th Infantry Regiment, part of the 32nd Infantry Division, on the road to the seaside village of Buna, probably November 1942 (right image). Neither the Australian militiamen (army reservists) nor the U.S. National Guardsmen of the 32nd Division were well trained or prepared for the tasks facing them along the 12‑mile/19‑km-long, Japanese-held Buna-Gona beachhead front despite being in the field for several months. On December 1 MacArthur testily told his third and last commander of the 32nd Division, Gen. Robert Eichelberger: “I want you to take Buna or not come back alive.” The stubborn Japanese were not prepared to relinquish their beachheads easily, and the Australian militiamen and American national guardsmen received a brutal and bloody baptism of fire. The Australian 49th Battalion at Sanananda (between Buna and Gona) on December 7, 1942, lost 14 officers and 215 men in 5 hours of brutal and uncompromising fighting—48 percent of its fighting strength—for no gain. The Australian 55/53rd suffered comparable losses in their ill-fated attack—8 officers and 122 men. As for the battle-exhausted 32nd Division, whose total casualty count of 9,956 exceeded its entire battle strength—it needed 6 months to reconstitute before its next operation, returning to New Guinea in October 1943 and taking part in the liberation of the Philippines beginning the following October 1944.

|  |

Left: Three GIs lie dead at low tide on Buna Beach near a wrecked landing craft. This image by LIFE magazine’s George Strock taken in February 1943 was not published until September 20, 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized its release, the first image of clearly visible American dead on a World War II battlefield. (U.S. military censors placed no restrictions on photos of enemy war dead.) FDR was anxious that the public, far removed from the war’s front lines, was growing complacent over the toll the war exacted on American lives. Soon images like this became an accepted part of the public’s vision of the war.

![]()

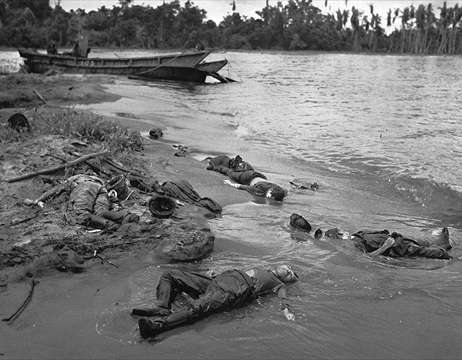

Right: Japanese soldiers killed during the desperate final phase of the battle at Buna Mission (Australian government station), which fell on January 2, 1943. (Photo by George Strock.) Even before the new year the Japanese had lost air and naval superiority. Increasingly, they were powerless to disrupt the Allies’ supply chain and were unable to resupply their troops by destroyers and nighttime submarines with ammunition and artillery shells, medicine (most of their garrison was debilitated by dysentery and assorted tropical maladies), and food. In December Japanese troopers were reduced to skin and bones, existing on 1‑3/4 oz/50 grams of rice and canned meat per day. Prevented by torrential rains, the Japanese took to stacking their dead in piles, which gave off such a hellish stench that service crews donned gas masks. After the Battle of Buna-Gona ended, the Allies found evidence of cannibalism of friend and foe alike among the Japanese.

Kokoda Trail Campaign: Day-by-Day

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click