KING, GOVERNMENT FLEE NORWAY TO ENGLAND

Tromsø, Occupied Norway • June 7, 1940

Within days of the German invasion of neutral Denmark and Norway on April 9, 1940 (Operation Weseruebung), it became clear that the Norwegian armed forces could not resist the more powerful Wehrmacht (German armed forces), bristling with modern weaponry and supported by highly effective air cover. Caught largely by surprise, the military’s initial defense in the south of Norway was largely disorganized and ineffectual, though sufficient to allow King Haakon VII and his government to escape capture. A solution along the lines achieved in Denmark, which capitulated to the Germans on Day 1 of the invasion, would appear to have spared the nation many deaths and much destruction. Nevertheless, an organized and spirited military defense and counterattacks in parts of Western and Northern Norway began, aimed at securing strategic positions along the coast with the help of British, French, and Polish forces.

The May 10, 1940, Nazi invasion of France, which managed to corner the broken remains of the French Army and the British Expeditionary Force in the Dunkirk pocket (May 21 to June 4), knocked that plan into a cocked hat. On this date, June 7, 1940, the Norwegian government held its last meeting on Norwegian soil in Tromsø nearly 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle and far from the nearest German lines. A few hours later the king, crown prince, members of the government, and the diplomatic corps—a total of 400 passengers—boarded the British heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire for exile in England. All serviceable Norwegian naval vessels, aircraft with adequate range, and merchant ships joined the exodus.

Late the next night the order to demobilize the remaining Norwegian armed forces was issued. The Germans did not interfere. The German and northern Norwegian commands signed a ceasefire on June 10, 1940. The ceasefire did not prevent Norway’s legitimate government—now operating out of London—from continuing the struggle as a member of the Allies against the German invaders. Most Norwegians remained loyal to their king, and patriots did not hesitate to ridicule Vidkun Quisling (1887–1945) and his collaborationist government in Oslo. (The word “Quisling” entered the English language as a synonym for “traitor.”) The Milorg resistance movement, which began life as a small sabotage unit but ended up as a 40,000‑strong military force, played a crucial role in forcing German capitulation in Norway in May 1945, where 100,000 German troops were still stationed, and in stabilizing the country during the postwar years.

Norwegian Resistance to Nazi Occupation, 1940–1945

|  |

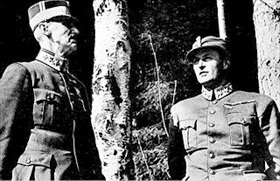

Left: Norwegian King Haakon VII and Crown Prince Olav sought shelter in the area of Molde on the country’s west coast during a German bombing of the town in April 1940. The Luftwaffe endeavored to kill the king, the royal family, and members of the legitimate Norwegian government after their successful escape from Oslo in the aftermath of the German invasion of Norway. The king, his family, and his government were conveyed by a British cruiser 600 miles north to Tromsø, where they established a provisional capital on May 1, 1940.

![]()

Right: Norwegian refugees cross the border into Sweden. Throughout the war years, a number of Norwegians fled from the reaches of the Quisling regime. These included Norwegian Jews, political activists, and others who had reason to fear for their lives. Norwegian border patrols were established to stop these flights across the long border with Sweden, but locals who knew the woods found ways to bypass them.

|  |

Left: Norway’s eastern neighbor Sweden, neutral by circumstance of geography and national survival (there were more than a quarter-million German troops near her borders), nevertheless surreptitiously aided the Norwegian resistance movement with training and equipment in a series of camps it set up in mid-1943. To avoid suspicion, the Swedes camouflaged the camps as police training camps. (A camp for Danish police troops was located in Sofielund across the Øresund strait from occupied Denmark.) Funding for the Norwegian camps came from the Norwegian exile government in London. By 1944, some 7,000–8,000 men had been trained in Sweden. After the German capitulation in Oslo in May 1945, around 13,000 police troops were transferred to Norway to help bring security and stability to the new government.

![]()

Right: Armed only with a handgun, Col. Terje Rollem (1915–1993), Milorg district chief for Oslo, assumed command of Oslo’s medieval Akershus Fortress on behalf of the Norwegian Resistance, May 11, 1945. The handover occurred in front of the German commandant’s residence four days after Reichs President Adm. Karl Doenitz (successor to deceased Fuehrer Adolf Hitler) had capitulated his armed forces unconditionally to the Allied powers in Berlin. Rollem and the commandant’s adjutant (right in photograph) walked around the castle grounds, substituting Milorg men for German guards, who were taken to a POW camp. This iconic photo of German commandant Major Josef Nichterlein stiffly saluting the victor came to be displayed in homes all across Norway as a symbol of the country’s liberation.

Operation Weseruebung: German Invasion and Occupation of Norway and Denmark

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click