JAPAN’S LEADERS PUSHED TO END WAR

Tokyo, Japan · June 22, 1945

Beginning in the summer of 1944 Japanese military prowess fast approached terminal collapse in the Pacific. Between mid-June and early August, Saipan and Guam in the Marianas fell to superior American forces. Peleliu and Angaur in the Palau Islands were in American hands by the end of November 1944. In the Philippines, Leyte Gulf, Luzon, and Manila were wrestled from the Japanese, though the contest on Luzon Island lasted to the end of the war. Between late February and mid-June 1945 Japanese garrisons on Iwo Jima and Okinawa in the Volcano and Ryukyu island groups, respectively, fell to the enemy, now within easy striking distance (540 miles/869 kilometer) of Kyūshū, the southernmost of the four Japanese main islands.

Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) was rattled enough by American landings in January 1945 on Japanese-occupied Luzon, the main Philippine island, that he discretely met in February with seven senior statesmen (jushin), six of whom were former prime ministers, querying them on how the country should bring an end to the war. The emperor had long harbored a desire to restore peace between Japan and its enemies, dating as far back as the day after Pearl Harbor in December 1941, but now more pressing than ever in light of his country’s worsening military situation. Always his military advisers recommended against entering into peace negotiations with the Allies without notching one last victory. Hirohito told his military aide-de-camp on February 14, 1945, that he was unsure if his subjects “will be able to endure until then.”

The rivalry between the Army and Navy played out on the battlefield but also at the highest levels in Tokyo. As early as August 29, 1944, Navy personnel began conducting a clandestine survey of political and military leaders on what needed to be done to end the war. The more fanatical than realistic Army was determined to keep fighting to the bitter end, the battered Navy less so. A cabinet change on April 7, 1945, placed end-the-war advocates in the prime minister’s and foreign minister’s chairs with a mission, many higher-ups assumed, to end the war.

Despite the growing influence of the peace faction among Japan’s decision makers, on June 8 the coordinating body between Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki’s cabinet and Imperial General Headquarters—the Supreme War Leadership (or Direction) Council (Saikō sensō shidō kaigi), which was the highest decision-making body in Japan—formally reaffirmed the long-standing decision to engage the enemy to the last man. It was a setback. The next day Hirohito’s right-hand man at the imperial palace, Kōichi Kido, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, drafted “A Working Plan to Terminate the War.” The plan secured the approval of the emperor, the prime minister, and the navy and foreign ministers by the time Hirohito called the Supreme War Leadership Council into session on this date, June 22, 1945, to overturn the earlier bellicose fight-to-the-finish decision and prod council members to search for a political, not military, solution to terminate the war.

The tortuous path to peace took under 2 months, and in the waning days required Hirohito to issue two momentous and unprecedented “sacred imperial decisions” (seidans) before consensus was reached to surrender Japan unconditionally as required by the Allies in their Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945. Endorsed on August 10 and 14, 1945, by two Imperial Peace Conferences and the Suzuki cabinet, Hirohito announced the state decision the next day, August 15, to his war-weary subjects in a first-ever radio broadcast by a Japanese emperor.

Milestones on the Road to Unconditional Surrender

|  |

Left: Wartime photograph of Hirohito, seated in middle, as presiding head of an Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi). Convened by the Japanese government in the imperial palace in Hirohito’s presence, Imperial Conferences were extraconstitutional conferences that focused on foreign affairs of grave national importance. In the early hours of August 10, Hirohito, at the request of Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki, addressed the forum and resolved to embrace the Potsdam Declaration under one condition: preserving the emperor’s prerogatives as sovereign ruler. Suzuki and his cabinet—which included four members of the Supreme War Leadership Council—met immediately afterwards and unanimously endorsed Hirohito’s seidan, delivered in the emperor’s role as supreme military commander, and turned it into an official state decision to neutralize military hardliners. Four days later, in a second Imperial Conference that included Suzuki’s cabinet, Hirohito accepted U.S. surrender terms regarding the occupation and disarmament of his country and limits on his authority and that of the Japanese government to govern the state. The emperor’s second seidan was again transformed into an official government decision.

![]()

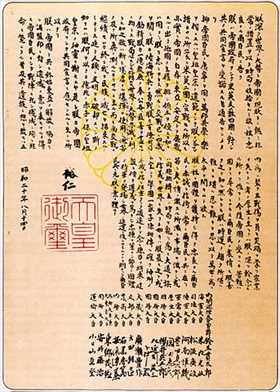

Right: Emperor Hirohito’s Rescript on the Termination of the War. The rescript was sanctioned by the emperor and approved by the Japanese cabinet on August 14 following the second Imperial Peace Conference. It was recorded by Hirohito in his high, shaking, unfamiliar voice on a phonograph record and broadcast to the nation at noon on August 15, 1945. In his Gyokuon-hōsō (lit. “Jewel Voice Broadcast”) Hirohito said he had instructed his government to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration fully without describing them. This circumlocution confused many listeners who were not sure if Japan had surrendered or if the emperor was exhorting his subjects to resist an enemy invasion. The poor audio quality of the radio broadcast, as well as the formal courtly language in which the speech was delivered, added to the confusion. A radio announcer’s rereading of emperor’s rescript in ordinary Japanese attempted to clarify its meaning.

Newsreel of Japanese Surrender Ceremony Aboard USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click