JAPANESE WEIGH DIPLOMACY VS. WAR WITH U.S.

Tokyo, Japan · September 6, 1941

On this date in 1941, in an Imperial Conference in Tokyo, Japanese officials concluded that if diplomatic measures could not reverse the U.S. policy of embargoing the export of various strategic raw materials (e.g., oil, iron ore, rubber, and scrap steel) to Japan by early October, then the government and military would implement the “Southern Plan,” or “Southern Advance”—attacking British and American bases in the Asia Pacific region and securing the oil-rich Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia) for the nation. (The “Southern Advance” became Japanese national policy in July 1940 when both the powerful Army and Navy leadership settled their strategic differences over potential areas of expansion. Germany’s invasion of France in May 1940 and the Soviet Union in June 1941 strengthened Japan’s flexibility when expanding to the south.)

On November 5, 1941, in another Imperial Conference, this one with Emperor Hirohito in attendance, Japanese officials were told by the hawkish Gen. Hideki Tōjō—war minister, home minister, and for the last 19 days prime minister as well—that Japan’s 73 million people must be prepared to go to war with the West if diplomacy with the U.S. and European colonial powers failed to improve relations and reverse trade restrictions, which the Japanese government labeled acts of aggression. (Imported oil, to give just one example of a strategic commodity now on the U.S. embargo list, made up about 80 percent of Japan’s domestic consumption, without which the nation’s economy, let alone its brutal expansion in China, would come to a halt.) The time for military action was tentatively set for December 1, 1941.

Two weeks later, on November 18, 1941, the Japanese Diet (parliament) approved a resolution of hostility against the United States. Japan’s attacks on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, the British crown colony of Hong Kong, British Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, the U.S. Philippines, and U.S. outposts on Wake and Guam islands on December 7 and 8, 1941, drew the U.S. and its European allies into an exhausting, brutal, and costly Asia Pacific war whose outcome in Japan’s favor, in the view of Pearl Harbor architect Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, was highly problematic to start with. Only after the destruction of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—combined with the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan—provided irrefutable evidence of a no-win situation for Japan were Hirohito and the Supreme War Council pushed over the edge to sue for peace in mid‑August 1945.

![]()

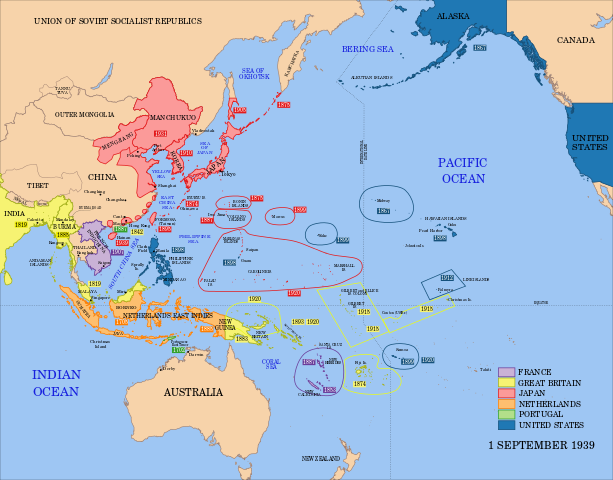

Asia Pacific on the Eve of War, 1939

|

Above: Political map of Japanese, European, and U.S. possessions in the Asia Pacific region on the eve of the Pacific War, September 1, 1939. Japanese control in China was tenuous.

|  |

Left: Emperor Hirohito (1926–1989) in dress uniform, 1935. On November 2, 1941, Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) gave his consent for his country to wage war against the United States. The next day the emperor was briefed in detail on the proposed sneak attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Two days later, on November 5, 1941, Hirohito approved the operations plan for the war and continued to hold meetings with the military chiefs and Army Minister/Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō until the end of the month. On December 1, another conference finally sanctioned the war against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands.

![]()

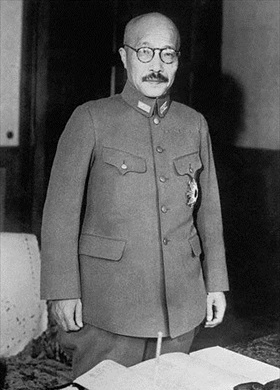

Right: Gen. Hideki Tōjō (1884–1948) in military uniform. On July 22, 1940, Tōjō was appointed Japanese Army Minister. During most of the Pacific War, from October 17, 1941, to July 22, 1944, he served as prime minister as well. In that capacity he was directly responsible for the deadly attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war Tōjō was arrested, sentenced to death for war crimes by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, and hanged on December 23, 1948.

|  |

Left: Soldiers parading before Shōwa Emperor Hirohito. Prior to and during World War II, Hirohito was shown in photos and newsreels riding Shirayuki (White Snow), his beautiful white stallion. The California-born stock horse was part of his carefully cultivated warrior image. A news agency reported that Hirohito made 344 appearances on Shirayuki.

![]()

Right: Wartime photograph of Hirohito, seated in middle, as presiding head of the Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi). Convened by the Japanese government in Hirohito’s presence, the Imperial Conference was an extraconstitutional conference that focused on foreign affairs of grave national importance. Hirohito was also a member of the Imperial General Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference. Liaison Conferences coordinated the wartime efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy. In terms of function, it was roughly equivalent to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Final decisions of Liaison Conferences were formally disclosed and approved at Imperial Conferences.

Japanese Expansionism Before and During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click