JAPANESE TROOPS LAND ON LUZON

Manila, Philippines · December 10, 1941

On this date in 1941, three days after the U.S. Pacific fleet had been crippled at Pearl Harbor, Japanese troops landed on the U.S.-held island of Guam in the western Pacific Ocean and occupied it within hours. On the same day elements of the Japanese 14th Area Army under Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma began swarming ashore at Lingayen Gulf on the large Philippine island of Luzon, over 100 miles north of Manila, the Philippine capital; more followed on December 22. (The largely self-governing Philippines was a U.S. possession from 1898 to 1946.) Gen. Douglas MacArthur, whom President Franklin D. Roosevelt had named commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East on July 26, 1941, led a force of 140,000 mostly Filipino defenders (the Philippine Army had been “federalized” in July), who were dispersed around the archipelago. Willfully blind to the impending crisis, MacArthur had boasted before Pearl Harbor that he was ready to meet any Japanese thrust. Sitting in his headquarters in an historic old fortress in Manila, the general found his forces unprepared, underequipped, and quickly shorn of air and naval support as the end of December approached. Outmatched by Japanese air and sea superiority, MacArthur abandoned efforts to defend Manila on Christmas Eve, declaring the capital an “open city,” and ordered his troops to the mountainous, thickly forested Bataan Peninsula, which forms the western side of Manila Bay. This they reached in January 1942. The outnumbered troops held out until April 9, and those on the tadpole-shaped “rock” of Corregidor in Manila Bay held out until May 6. It was the single-largest defeat in American military history, matched only by the British surrender of their island fortress, Singapore, on the tip of the Malay Peninsula on February 15, 1942. Nearly 80,000 U.S. and Filipino troops were sent into a cruel captivity, many of them dying in the subsequent “death march” out of Bataan. MacArthur, who was ordered by Roosevelt to leave Corregidor in mid-March to assume command of Allied forces in Australia, promised the islanders, “I shall return,” which he famously did for photographers on October 20, 1944, striding confidently through knee-deep surf toward the beach on Leyte Island.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1849086095,1585671185,1603447415,1565124340,1591149568,0815410859,1841767891,0312429703,1439199655,1453647627″ /]

Japanese Conquest of the Philippines, December 8, 1941, to May 6, 1942

|  |

Left: Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, and, to his right, Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, October 10, 1941. The USAFFE comprised four tactical commands and were a mixed force of U.S. and Filipino non-combat-experienced regular, national guard, constabulary, and newly created Commonwealth units. Wainwright commanded the North Luzon Force, which defended both the most likely sites for Japanese amphibious attacks and the central plains of Luzon.

![]()

Right: Japanese Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma, 14th Army Commander, coming ashore at Lingayen Gulf, December 24, 1941. On November 6, 1941—one month and a day before the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor—Homma’s 14th Army was formed for the specific task of invading and occupying the Philippines. The 14th Army was a part of Japan’s Southern Expeditionary Army Group. (The Southern Expeditionary Army Group, also formed on November 6, 1941, was ordered to prepare for war in the event that negotiations with the United States did not succeed in peacefully meeting Japanese objectives.) Comprised of four corps-equivalent armies, the Southern Expeditionary Army Group, led by former Minister of War Gen. Count Hisaichi Terauchi, was responsible for all military operations in the Southeast Asian and Southwest Pacific campaigns until its surrender (680,000 Japanese soldiers strong) on September 12, 1945.

|  |

Left: U.S. and Filipino POWs after their surrender on Bataan Peninsula on April 9, 1942. The Japanese victory following the Battle of Bataan (January 7 to April 9, 1942) hastened the fall of the island bastion of Corregidor, 2 miles away, a month later. More than 60,000 Filipino and 15,000 American prisoners of war were forced into the infamous Bataan Death March.

![]()

Right: Surrender of U.S. forces at the Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor, May 6, 1942. The Battle of Corregidor (May 5–6, 1942) was the culmination of the Japanese campaign for the conquest of the Philippines. Corregidor, with its network of tunnels and formidable array of defensive armament, along with the fortifications across the entrance to Manila Bay, was the remaining obstacle to Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma’s 14th Japanese Army. Corregidor and the neighboring islets denied the Japanese the use of Manila Bay, but the Japanese Army brought heavy artillery to the southern end of Bataan and proceeded to block Corregidor from any sources of food and fresh water. On May 6, 1942, Japanese troops forced the surrender of the remaining American and Filipino forces, which were under the command of MacArthur’s man-on-the-spot in the Philippines, Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright.

|  |

Above: U.S. prisoners of war on the “death march” from Bataan to their prison camp, c. May 1942 (left photo). Homma’s 14th Area Army was responsible for the harrowing 80‑mile forced march of U.S. and Filipino prisoners following Bataan’s surrender. The Bataan Death March was characterized by widespread mistreatment (lack of food and water), physical abuse (beatings and bayoneting,) and murder by “cleanup crews” who killed those too exhausted to continue (right photo). Approximately 2,500–10,000 Filipinos and 100–650 Americans died before they could reach their destination. As a consequence, Homma was executed by firing squad after being convicted by the U.S. military tribunal for war crimes in the Philippines.

|

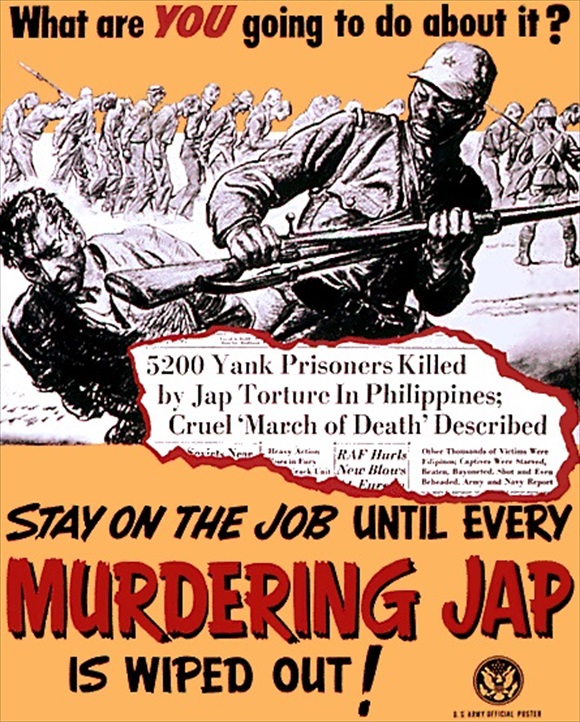

Above: The Bataan Death March and other Japanese actions were used to arouse fury in the United States, as reflected in this U.S. Army poster. Interestingly, it wasn’t until January 27, 1944, that the U.S. government informed the public about the death march.

Japanese Forces Occupy the Philippines, 1941–1942 (Set to Martial Music)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click