JAPANESE SUB I-58 SINKS HEAVY CRUISER USS INDIANAPOLIS

Philippine Sea Between Guam Island and Leyte Gulf • July 30, 1945

On July 15, 1945, Capt. Charles B. McVay III, 46‑year-old skipper of the USS Indianapolis, a fast Portland-class cruiser in California for repairs, received orders to pick up some special cargo at Hunters Point (predecessor name for the now-closed San Francisco Naval Yard). Eleven days later, on July 26, Indianapolis unloaded her mysterious cargo—a large crate that had been secured to its deck and a 2‑ft.-long metal cylinder placed in the flag lieutenant’s cabin—all delivered under tight security to the B‑29 Superfortress heavy bomber base on the Central Pacific island of Tinian in the Marianas. Of course, the key item on Indianapolis’ top-secret cargo manifest was none other than the precious fissile components for “Little Boy,” the codename for the atomic bomb that would obliterate Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945.

Four days after leaving Tinian, just after midnight on this date, July 30, 1945, 6 Type 95 wakeless torpedoes, the fastest and most deadly in use by any underwater navy in World War II, were launched, 3 seconds apart, by Japanese submarine I‑58, 36‑year-old Lt. Cdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto commanding. Two 1,200‑pound/544-kilogram warheads struck the Indianapolis 50 seconds later, one in the starboard bow and one amidships, as the heavy cruiser was en route to Leyte Gulf in the Philippines for gunnery drills in anticipation of the Allied invasion of Japan. In so doing I‑58 inflicted the greatest loss of life in U.S. naval history: 300 officers, sailors, and Marines were killed in the 27‑minute attack, and the remaining 896 of the ship’s complement bobbed in the unforgiving sun and shark-infested waters of the South Pacific for 4 days and nights without the U.S. Navy having a clue the ship was missing. When at last the bobbing men were accidentally spotted by a Navy patrol bomber on a routine mission and rescued the next day, August 3, just 316 out of the original 1,196 sailors and Marines had survived the sinking, exposure to oil, sun, and sea, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and prowling sharks—reputedly the most shark attacks on humans in history. News of the tragedy was withheld from the American public for 16 days and went largely unnoticed owing to the momentous events of August 6 and 9 on the Japanese homeland.

The tragic demise of Indianapolis and the fate of her crew was not assuaged by scapegoating Capt. Charles McVay in a Naval court-martial convened in late 1945. It was the judgment of the court that McVay was culpable for the loss of his ship and crew. Although Indianapolis had a top speed of 32.5 knots/52 km/h, the fast cruiser had neither escort vessel (requested but rejected as unnecessary) nor underwater detection equipment, which conceivably could have altered events. Worse, McVay was denied vital information about a group of Japanese submarines operating in close proximity of the Indianapolis’ route. The ill-fated cruiser was on her own in presumably safe waters. The panel of judges came down on McVay for “hazarding his ship” by failing to steam in a zigzag pattern. According to Lt. Cdr. Hashimoto’s own (entirely believable) testimony at McVay’s court-martial, zigzagging wouldn’t have mattered one bit. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz eventually remitted McVay’s sentence, although his conviction stayed on the books. McVay was restored to active duty and remained in the Navy until he retired in June 1949 as a rear admiral. But the deaths of his men in the ocean continued to haunt him until, on November 6, 1968, he killed himself. The Indianapolis had tragically claimed its last victim. Thirty-two years passed before an act of the U.S. Congress exonerated the ex-skipper.

USS Indianapolis and Japanese Sub I-58, July 1945

|  |

Left: USS Indianapolis off California’s Mare Island, JJuly 10, 1945, days after the heavy cruiser’s final overhaul and repair of combat damage (incurred on March 31, 1945, off Okinawa) and 5 days before setting off for the Central Pacific island of Tinian to deliver critical elements of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. The 9,800‑ton, 610‑foot/186‑meter-long heavy cruiser served in numerous headline-grabbing naval engagements, among them the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Battle of Midway, the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Battle of Iwo Jima, and the Battle of Okinawa. Indianapolis served as a fleet flagship for Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance when he commanded the U.S. Fifth Fleet in its battles across the Central Pacific. Sunk a half month before Japan’s unconditional surrender, Indianapolis was the last victim of the Japanese Navy.![]()

Right: U.S. Navy preparing I‑58 for scuttling, April 1, 1946. I‑58 was a Type B3 submarine built and launched in June 1943 and displaced 2,200 tons. Jet-black and sleek, it was one-and-a-half times larger than the new Balao‑class American subs. Three hundred and fifty feet/107 meters long and with 2 Kampon diesel engines producing 4,700 hp, I‑58 could cruise 21,000 miles/33,796 kilometers at 17 knots/31 km/h on the surface and 12 knots/22 km/h submerged, a very respectable distance and speed for an underwater boat. One of the best and most skilled submarine officers in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 36‑year-old Lt. Cdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto commanded I‑58’s crew of 107 officers and enlisted men, many of whom he chose from other subs he had served on since becoming torpedo officer on I‑24 in October 1941.

|  |

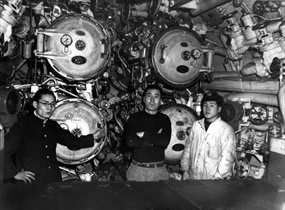

Left: This view of I‑58’s torpedo room shows 3 crewmen standing in front of the breach end of 4 21 in./533 mm torpedo tubes. (The 2 lowest tubes can’t be seen.) The photo was taken at Sasebo naval base in occupied Japan in 1946. I‑class vessels had 6 tubes in the bow and none at the stern in contrast to American, British, and German subs, which had both bow and stern torpedo tubes. The I‑class boats carried 19 Type 95 wakeless torpedoes, the fastest and deadliest in use by any navy in World War II. The Type 95 was second only to the famous Type 93 Long Lance used by Japanese surface ships. A real ship killer at more than 23 feet/7 meters-long and 3,600 lb/15.9 kg, the Type 95 could travel up to 12,000 yards/10,973 meters at nearly 56 knots/104 km/h. The warhead weighed 1,200 lb/544 kg, giving it considerably more punch than American Mark 14 and Mark 16 torpedoes. Adding to I‑58’s deadly torpedo arsenal were 4 Type 1 Kaiten human torpedoes. These were modified Long Lance torpedoes fitted with a 1‑way pilot’s compartment and were suspended from the sub’s deck during transit. Kaitens had few successes when loosed on U.S. ships. Kaiten pilots sunk just 3 U.S. ships during the Pacific War for a loss of 106 of their craft. Hashimoto, being the skilled torpedo officer that he was, stuck by his training and experience and sent the USS Indianapolis and the bulk of her crew to their deaths using his trusty Type 95 torpedoes.

![]()

Right: This photo is believed to depict crewmen in action aboard the I‑58 in 1945 shortly before the fateful encounter with Indianapolis. Up until then I‑58 had failed to sink a single enemy ship. Against his better judgment Hashimoto sent 2 Kaitens to strike a U.S. tanker and escorting destroyer 3 days before sinking the Indianapolis. Neither Kaiten was successful, and the explosions Hashimoto heard on his acoustical headphone were likely the torpedo pilots self-destructing.

USS Indianapolis Documentary. Skip First 3 Minutes

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click