JAPANESE SCORE TACTICAL VICTORY IN BATTLE OF CORAL SEA

With Rear Adm. Fletcher’s Task Force 17 • May 7, 1942

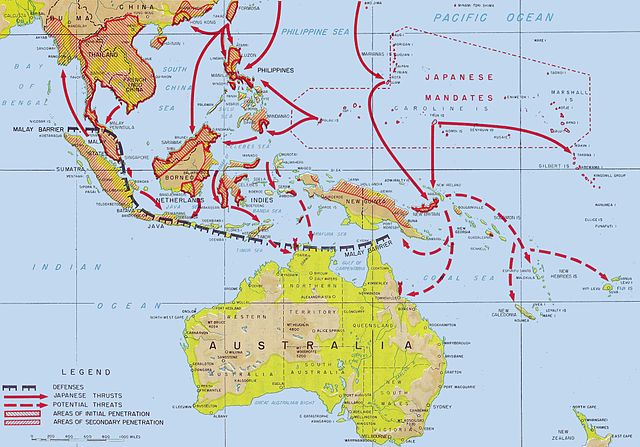

In the 6 months following Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on U.S. naval and air facilities at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the Japanese had the advantage of dominant air and naval power in the Pacific Ocean region. During these months the Japanese military looked to expand its conquests beyond those countries and European colonial possessions already forced into Japan’s East Asia constellation—British Malaya, Thailand, Burma, the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), and the American possession of the Philippines. Japanese control over the Solomon Islands chain, for example, would have the benefit of effectively severing U.S. trans-Pacific transit to and from New Zealand and Australia, both countries at war with Japan since December 1941. Seizing the Australian-administered territory on the large island of New Guinea, less than 100 miles/161 kilometers north of the Australian mainland, would give Japan naval and air bases at Port Moresby, the last bases between Australia and Japan in hostile hands, thus conferring effective dominance of the Coral Sea and virtually all of Australia’s northern and eastern coasts (see map below).

Fortunately for the Allies, U.S. cryptanalysts had deciphered Japanese naval messages that clearly indicated the enemy intended to capture Port Moresby and Tulagi in the southern Solomons in early May 1942. A formidable Japanese strike force of flattops, cruisers, and destoyers would cover the amphibious assault forces in an offensive the Japanese called Operation Mo (Mo Sakusen), short for Port Moresby Operation. Two U.S. carrier task forces and a joint U.S.-Australian cruiser force under U.S. Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher were dispatched to challenge the Japanese.

Beginning on this date, May 7, 1942, the carrier forces from each side engaged in airstrikes over 2 consecutive days. On the first day U.S. carrier planes sank the Japanese light carrier Shōhō, which was covering the Port Moresby invasion force, while Japanese aircraft sank a U.S. destroyer. On May 8 carrier aircraft from both sides found the other’s fleet carriers, U.S. planes heavily damaging the Shōkaku and inflicting modest damage to the Zuikaku, while Japanese planes fatally damaged the USS Lexington and severely damaged the Yorktown. Afterwards the combatant forces disengaged and retired from the battle area. Because of a critical loss of carrier air cover, the Japanese recalled the Port Moresby invasion fleet on May 10.

In the wake of the Operation Mo setback, the Japanese Army commenced in mid‑July 1942 an ultimately unsuccessful campaign to take Port Moresby with an overland approach across the Owen Stanley Range via the Kokoda Track from Buna and Gona in Papua New Guinea. Over 6,250 Japanese soldiers lost their lives during the Kokoda Track Campaign. Japanese air group losses from losing the light carrier Shōhō and from damage sustained by the Shōkaku and Zuikaku persuaded the Japanese Navy to send the 2 fleet carriers back to Japan for replacement pilots and aircraft. The absence of all 3 Operation Mo flattops the next month in the North Pacific contributed to the disastrous Japanese outcome in the Battle of Midway (June 4–7, 1942). The upshot of that 4‑day naval engagement was the loss of 4 Japanese fleet carriers (the core of Japan’s naval offensive forces), 248 aircraft, and between 3,000‑plus and nearly 5,000 sailors and airmen (sources vary). The U.S. Navy’s victory near Midway Atoll precipitated the sharp decline of Japan’s strategic initiative and naval superiority in the Pacific Theater. From 1943 onward, the Japanese neither conquered nor kept another square inch of Pacific soil while their adversaries reaped the opposite returns.

Battle of the Coral Sea, May 7–10, 1942: First Carrier-to-Carrier Engagement

|

Above: Reddish hashed areas in this map indicate where the Japanese had made advances in the Southwest Pacific and Southeast Asia areas between December 1941 and April 1942. Port Moresby, the seat of Australian-administered New Guinea, lies on the island’s “tail” where the broken-line arrow points left and upward (center right in map). The words Coral Sea can be seen under the longer left-facing broken-line arrow pointed at the northeastern coast of Australia. The Solomon Islands lie to the left of the broken-line “lobster tail” arrow and north of the lobster’s two arms. Seizing Port Moresby and a series of other islands and ports, including Tulagi in the Solomons, would strengthen Japan’s southern defensive screen, further isolate Australia, and bring immense benefits to securing Japan’s earlier expansion in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. On May 10, 1942, the Japanese abruptly called off their seaborne invasion of Port Moresby, the operation that had initiated the pivotal naval Battle of the Coral Sea.

|  |

Left: Japanese light carrier Shōhō under attack by U.S. Navy planes on May 7, 1942, during the Battle of the Coral Sea. Nine bomb hits and four torpedoes from U.S. carriers Yorktown and Lexington sank the Shōhō within five minutes after the first blow was scored. The Shōhō, with a complement of 785 officers and men and 30 aircraft, was on her first combat operation and was the first Japanese aircraft carrier to be sunk during World War II. Too difficult to distinguish in the lower center of the photograph is a Douglas TBD Devastator, a U.S. torpedo bomber. Two or three other U.S. Navy aircraft are visible above the burning carrier. The photograph was taken by the aircrew of a U.S. Navy torpedo bomber from the Yorktown.

![]()

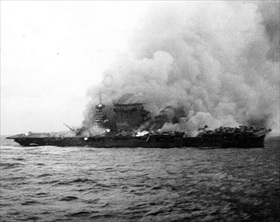

Right: U.S. fleet carrier Lexington burning after her crew abandoned ship during the Battle of the Coral Sea, May 8, 1942. Some 216 crewmen were killed and 2,735 evacuated. The “Lady Lex” sustained numerous hits from Japanese carrier aircraft. However, it was a series of massive explosions initially set off by sparks from electric motors that ignited gasoline vapors from ruptured fuel tanks that proved fatal to the flattop. Lexington’s surviving crew members were rescued. The valiant lady and the dead were sent to the ocean floor after Rear Adm. Fletcher ordered a U.S. destroyer to torpedo the flaming wreck.

Battle of the Coral Sea 1942: First Aircraft Carrier Battle in History

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click