JAPANESE SURGE INTO BRITAIN’S SINGAPORE STRONGHOLD

Singapore Island, British Malaya • February 8, 1942

On this night and the next day in 1942 in British Malaya (today’s Malaysia) Japanese forces surged over and soon pushed the British-led defenders back to the edges of the 220‑sq-mile/566‑sq-kilometer island of Singapore (the “Gibraltar of the East”), nearly 600 miles/966 kilometers from the initial Japanese landing sites. Singapore’s airfields fell—they were difficult to defend against attack—thereby permitting the quick resupply of the Japanese invaders. Issued an air-dropped ultimatum for the island’s surrender on February 11, Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival, land commander of Commonwealth forces (Indian, British, Australian, and Malay brigades) that were holed up in the southern sector of the island, surrendered his garrison on February 15.

Percival’s 85,000 troops, nearly 3 times the strength of their attackers and recently reinforced, were low on ammunition and drinking water. Many were tired from their retreat down the Malay Peninsula, and many were raw and untrained such as the 7,000 men of the 44th Indian Brigade, and most certainly underequipped. For instance, the British had zero tanks to the Japanese two hundred. Percival, who had only been in the British colony 6 months, complained later that war material which might have saved Singapore was instead sent to the Soviet Union and the Middle East, places where Great Britain was also heavily engaged.

During the course of the Japanese conquest of Malaya and Singapore the invaders took some 130,000 British, Australian, and Indian prisoners into a brutal captivity; some stayed in Singapore at the infamous Changi Prison, but many were transported in so-called “hell ships” to other parts of Asia, including Japan, to be used as slave labor. Some 60,000 Allied POWs were forced into building the infamous Thailand-Burma “Death Railway” between Bangkok and Rangoon (Yangon) in support of the Japanese campaign in Burma (Myanmar). Over 10,000 never returned. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was appalled by Singapore’s surrender, calling it “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.” Earlier, from London Churchill demanded that Percival dismiss any thoughts of sparing troops or population defending Britain’s strategic Southeast Asian outpost. “Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honor of the British Empire and the British Army is at stake.” (A disaster on a similar scale was taking place next door in the American Philippines.)

Singapore’s surrender late in the afternoon of February 15, 1942, just 10 weeks into the Pacific War, permanently undermined Britain’s prestige as an imperial power in the Far East. It also gave Japan control of the Straits of Malacca—the chief sea route between the British-held Indian subcontinent and the mineral and agricultural riches of Southeast Asia. Percival survived his captivity in China and was on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay during the Japanese surrender ceremonies in September 1945. He also was witness to the Japanese surrender ceremonies in the reconquered Philippines with none other than Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, reversing the role Percival had played nearly 4 years earlier in Singapore.

Scenes from the Battle of Singapore, February 1942

|  |

Left: RAF Bristol Blenheim bombers lined up at Tengah Airfield, Singapore, February 8, 1941. The major airfield was impossible to defend, lying close to Japanese artillery across the Jahore Straits, the 1,100 yards/1,006 meters that separated the port city from the mainland. What is more, the British had less than half the 600 faster and more deadly planes the Japanese had. The enemy quickly dominated the skies, demolished airfields, and destroyed the British and Australian air forces. Few British 15‑inch/38.1‑centimeter artillery pieces faced landward; the mass of Singapore’s defenses were set up to oppose a seaborne invasion that never came.

![]()

Right: Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival, escorted by a Japanese officer through enemy lines, walks beside the Union Flag under a white flag of truce to negotiate the capitulation of Commonwealth forces in Singapore, February 15, 1942. Photographs of the defeat went around a stunned world. It was the largest and most humiliating surrender of British-led forces in history and led directly to the imprisonment, torture, and death for thousands of British and Commonwealth men and women, soldiers and civilians alike. For many Singaporeans, Malays, Chinese, and Indians there was a strong feeling that Britain had left them to the mercy of a brutal Japanese occupation. Across Asia, the defeat was viewed as an Imperial disgrace. In India, British prestige was shattered. Resentment simmered in Australia for decades.

|  |

Left: Surrendering troops of the Suffolk Regiment held at gunpoint by Japanese infantry in the battle of Singapore. Men from the regiment suffered great hardship as prisoners of war and only a few survived their captivity.

![]()

Right: Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita (seated, center), the short, heavy-set, pudgy-face commander of the Japanese Twenty-Fifth Army, pounds the table to emphasize his terms—unconditional surrender. Percival sits between his officers, clenched hand to mouth, looking weak and puny at the negotiating table. In December 1945 an American military tribunal in Manila convicted Yamashita of war crimes relating to the many Japanese atrocities in the Philippines (Yamashita’s last command) and Malaya and Singapore (his first) against wounded soldiers, civilians, and prisoners of war (tens of thousands were slaughtered). The “Tiger of Malaya,” as Yamashita was known, was ordered hanged in February 1946.

|  |

Left: Elements of the Japanese Twenty-Fifth Army march through Fullerton Square in the center of Singapore, February 1942. The Twenty-Fifth Army served primarily as a garrison force for the occupied territories. The Fullerton Building at 1 Fullerton Square seen here on the left became the headquarters of the Japanese Military Administration in Singapore. It was here that Lt. Gen. Yamashita received a check for $50 million from the Singapore and Malay Chinese community as recompense for their alleged crimes against the Japanese. Today the building is a Singapore national monument and houses the posh Fullerton Hotel.

![]()

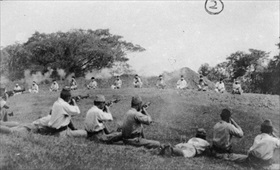

Right: Japanese soldiers shoot Indian (Sikh) POWs, captured Commonwealth soldiers who sit blindfolded in a rough semi-circle about 20 yards/14 meters away. (Indian divisions were the backbone of British forces in Singapore.) This photograph was one of four found among Japanese records when British troops reentered Singapore in 1945. Japanese soldiers also sought vengeance against huge numbers of Chinese civilians who had settled in Singapore, executing between 50,000 and 100,000 young Chinese men, most infamously in the Sook Ching massacre, which took place between February 18 and March 4, 1942, at various places in Singapore and Malaya. Malays were not spared either.

Fall of Singapore, December 1941 to February 1942

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click