JAPANESE ON U.S. WEST COAST TO BE FORCIBLY RELOCATED

Washington, D.C. • February 19, 1942

Eighty-three years ago on this date in 1942, celebrated today as the Day of Remembrance, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It authorized the War Department to designate “military areas” in the U.S. and admit, exclude, or remove from these areas anyone whom the department felt to be a danger to the security of the nation. The next month Roosevelt signed an Act of Congress that made any violation of mandates issued under his executive order (e.g., public proclamations issued by senior military authorities) a federal crime. Although the unprecedented order appeared carefully neutral, Executive Order 9066 ultimately led to the tragic exile and incarceration of almost 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, citizens and noncitizens alike, living along the U.S. West Coast.

Approximately 80,000 of those interned under FDR’s executive order were second- and third-generation American citizens born in the United States (Nisei and Sansei, respectively), not-so-cleverly reclassified by the government as “non-aliens” in a ham-fisted suspension of their birthright under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Almost half of those incarcerated were children born in the U.S. (In Canada, 22,000 Japanese nationals and Canadian-born Japanese [the latter population representing 62 percent of the total] suffered similar or worse treatment: the Canadian government confiscated and sold their property to help defray the cost of relocating and detaining them. South of the border almost 5,000 Japanese were evicted from Mexico’s Pacific Coast and plunked down in Mexico City and Guadalajara.) Suddenly uprooted from their homes, workplaces, places of worship and learning, and deprived of or forced to sell off practically everything they had acquired over a lifetime (Japanese nationals had their bank accounts frozen), native-born Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals residing in the U.S. (known as Issei; with a single exception, first-generation Japanese were prevented by law from acquiring U.S. citizenship) were taken first to 1 of 15 assembly centers, or temporary detention camps. California’s San Joaquin County Fairgrounds and the Santa Anita and Tanforan racetrack stables, still reeking of their former 4‑legged occupants, were 3 converted temporary camps. Then they were shipped to any of 10 permanent inland relocation centers where they were held without due process of law “for the duration” inside barbed wire enclosures, watched over by armed military police (see map below).

Notwithstanding that America was at war with both Japan and Nazi Germany, Hawaiians of Japanese ancestry and German Americans and German U.S. residents were not interned en masse and therefore escaped disenfranchisement, measureless separation, precious lost years, miserable deprivation, monotonous camp routine, enforced idleness, and dependence on the U.S. government for their food and shelter. Under the U.S. Justice Department’s Enemy Alien Control Program, the government detained and interned just over 11,000 German enemy aliens, as well as a small number of German American citizens, either naturalized or native born. The population of German citizens in the United States—not to mention American citizens of German birth—was far too large for a general policy of disenfranchisement and mass confinement comparable to that used against people of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei). Instead, German citizens were detained and removed from coastal areas on an individual basis. The evictions amounted to only several hundred. In addition, over 4,500 ethnic Germans were brought to the U.S. from Central and South America and the Caribbean island of Cuba and similarly detained based on a list covertly drawn up by the Federal Bureau of Investigation with the encouragement of President Roosevelt. The FBI suspected these Germans of subversive activities abroad and demanded the eviction of these “dangerous Axis agents” to this country for detention in camps operated by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service and the Justice Department or else their repatriation to Germany. Many Germans had been residents of Latin America for years, some for decades. Nine Latin American countries and Canada set up their own Axis internment camps. Only pro-Fascist Argentina refused to play along.

Executive Order 9066 Cleared the Way for the Forced Exile and Relocation of West Coast Enemy Aliens and Japanese Americans to a New Existence in Confinement Centers Far from Their Homes

|

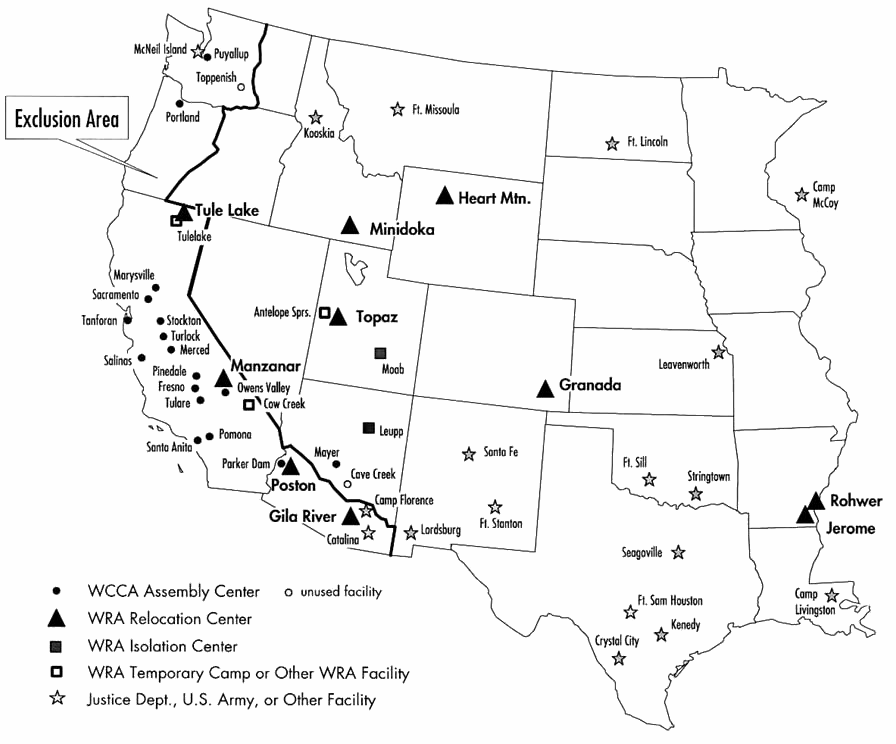

Above: Map showing (a) the massive West Coast World War II exclusion area (Military Areas 1 and 2) and (b) sites of confinement in the continental U.S. for Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals residing in 4 Western states. The 10 hastily built detention sites, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” are identified by black triangles. The sites were built in 7 states all west of the Mississippi River. All the sites were remote; many were situated in desolate deserts or swamp land. It was to these often former Civilian Conservation Corps camps that Japanese arrested between December 8, 1941, and early 1942 were exiled indefinitely—that is, before Executive Order 9066 was in place. Roughly 75,000 Japanese American citizens and 45,000 Japanese nationals living in the U.S., a number equivalent to the population of Wilmington, N.C., would eventually be forcibly torn from their homes, neighborhoods, farms, fishing boats, and places of employment and worship in California (where the majority lived), Western Oregon and Washington, and Southern Arizona as part of the single-largest forced relocation in U.S. history. Eighty-five percent of all ethnic Japanese living in the continental U.S. were affected. In Hawaii, where 150,000-plus Japanese Americans comprised over one-third of the population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were removed to the mainland and incarcerated. On the Hawaiian island of Oahu, there were 17 incarceration sites, the largest and longest-operating being Honouliuli Internment Camp, which held 320 internees and 4,000 Japanese prisoners of war. In the map legend, WRA = War Relocation Authority and WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration, army’s predecessor to the civilian WRA.

|  |

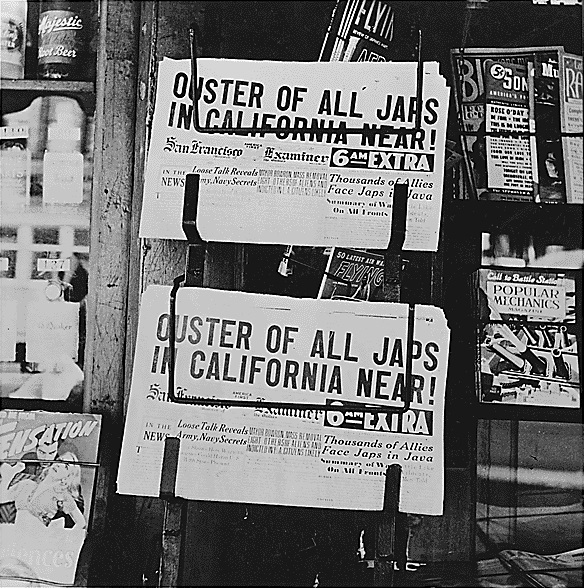

Left: “OUSTER OF ALL JAPS IN CALIFORNIA NEAR!” San Francisco Examiner headlines of Japanese relocation, February 27, 1942. On May 21, 1942, the rival San Francisco Chronicle told its readers: “S.F. Clear of All But 6 Sick Japs. . . . The last group, 274 of them, were moved yesterday.” Photo by Dorothea Lange. Lange was one of three photographers in the WRA Photography Section, or WRAPS, in 1942–1943. The other two were Clem Albers and Francis Stewart.

![]()

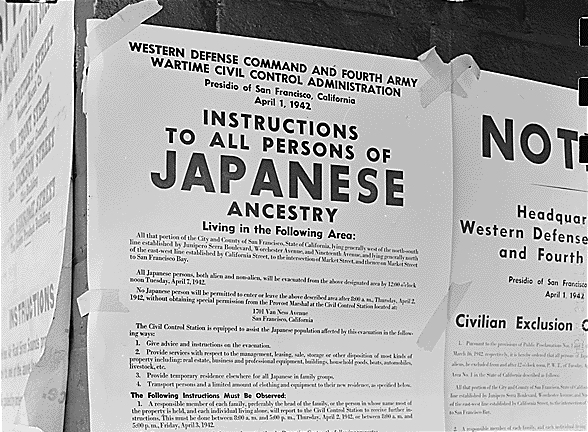

Right: Official notice of exclusion and removal, dated April 1, 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange, April 11, 1942. The exclusion order posted at First and Front streets in San Francisco directed the removal of persons of Japanese ancestry from the first San Francisco section to be affected by the evacuation. Years before the December 7, 1941, Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the U.S. government had drafted plans to intern some Japanese Americans and immigrant aliens and had already placed some West Coast communities under surveillance. This in spite of years’ worth of FBI and naval intelligence data that attested to residents of Japanese descent posing no national security threat. The exclusion order also swept up Japanese American soldiers who had taken an oath of allegiance to their country of birth.

|  |

Left: With luggage tags affixed to their clothing—an aid in keeping family units intact during all phases of their forced removal—members of the Moriji Mochida family await an evacuation bus in Hayward, Alameda County (San Francisco Bay area), California, May 8, 1942. On the luggage tags was written the family’s designated identification number. Mochida’s youngest child was 3. The Mochidas had operated a 2‑acre/0.8‑hectare nursery and 5 greenhouses in San Leandro, Alameda County, before their incarceration. Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

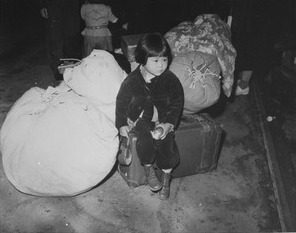

Right: The forced exodus of Japanese in Los Angeles started at the end of March 1942. Staring into uncertainty 2‑year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa, clutching a tiny purse and an apple with a few bites gone, waits with the family’s allotment of baggage before leaving a chaotic scene at Los Angeles’s Union Station. The child and her mother eventually arrived, like most Japanese Angeleno evacuees, at Manzanar War Relocation Center, more than 200 miles/322 kilometers north of LA in California’s Owens Valley, which would be their home for the next 3½ years. Each displaced family member was permitted to take bedding and linens (no mattresses), toilet articles, extra clothing, and “essential personal effects,” nothing more; in other words, only what could be carried. Photograph by Clem Albers.

|  |

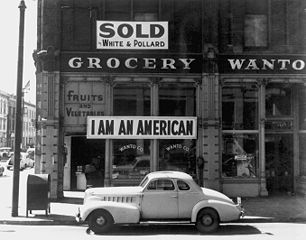

Left: This Oakland, California green grocer closed his store in March 1942 following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas (Military Area 1; see map above). The owner, a University of California graduate, had placed the “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign on his store front on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. Declarations like this San Francisco area store owner’s were insufficient to overcome the suspicion and contempt directed at people who looked like the enemy and who, it was commonly assumed at the time, remained loyal to Japan and its emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa). Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

Right: In 1944 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders, described by many Americans as the worst official civil rights violation of modern U.S. history. After years of lawsuits and negotiations, on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally acknowledged that the wartime exclusion, evacuation, and internment of Japanese Americans had been unreasonable. The act granted $20,000 in reparations to each surviving Japanese American (about 82,000 people), costing the U.S. Treasury $1.6 billion. (A month later the Canadian prime minister signed a similar settlement and apology.) It took a decade to locate all eligible U.S. recipients and deliver them their checks and formal apology. In 1991 survivors of the more than 2,200 Latin Americans of Japanese descent who were evicted by their governments and incarcerated in U.S. camps were compensated with a pitifully small $5,000 check. A late 20th-century study concluded that the internal government decisions that led to Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 9066 were based on racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.

Injustice Camouflaged as Military Necessity: Japanese American Internment During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click