JAPANESE MAKE THIRD ATTEMPT TO CAPTURE CHANGSHA

Changsha, Hunan Province, China • December 24, 1941

In the years since the political upheaval that brought Emperor Meiji to power (1868–1912), the Japanese began looking to the Asian mainland as a wellspring of new mineral, agricultural, and human resources to exploit for their use, benefit, and advantage. In the mid-1890s and 1905–1910 Japan brought the Korean Peninsula into its imperial orbit as well as the southern part of Liaodong Peninsula (Kwantung Leased Territory), formerly leased to Tsarist Russia. At the outbreak of the First World War Japan occupied German-leased territories in China’s coastal Shandong Province. (The 1919 Versailles Treaty confirmed the transfer to Japan of Germany’s rights in Shandong.) An agreement with Russia in 1916 helped secure Japan’s influence in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia on China’s northeastern and northern frontiers, respectively. Japan’s power in Asia grew with the demise of the tsarist regime and the disorder the 1917 Bolshevik (Soviet) Revolution left in Siberia. Japan contributed 70,000 troops to the Allied Expeditionary Force sent to Siberia in 1918.

Following stresses produced by World War I and the Great Depression, a militant Japanese nationalism flared up, prompting a full-blown invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the creation of a Japanese puppet state, Manchukuo. From then on the Japanese army in Manchukuo constantly skirmished with Chinese militias until 1937, when Japan’s armed forces captured both the Chinese port city of Shanghai and the Chinese Nationalist capital of Nanking (Nanjing). Those 2 conquests marked the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

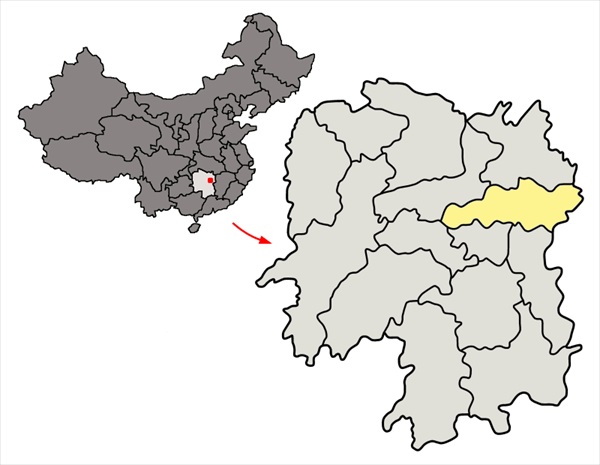

However, by 1941 Japan’s armed forces had become bogged down in China. What they needed was a killer offensive to defeat Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalist government, the Kuomintang (KMT), and its National Revolutionary Army. Twice, once in 1939 and again in 1940, the Nationalists had repulsed Japanese efforts to take the key city of Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province (see map below) and a city deep inside Chinese Nationalist territory. On this date in 1941, December 24, the Japanese opened their third assault on Changsha. Among their objectives as before: take Changsha, inflict maximum casualties on Chiang’s soldiers and airmen, weaken Chiang’s prestige, destablize the KMT by encouraging Chiang’s political rivals, and force Chiang’s hand in negotiating a Sino-Japanese peace. A pressing new objective emerged at the end of the year: prevent Chiang from solidifying the KMT supply line to or reinforcing British defenders bottled up in their crown colony of Hong Kong, now in Japanese crosshairs.

For the third time the Japanese air and ground assault on Changsha missed most of its objectives. Three days of heavy fighting in which the Japanese Eleventh Army tried battering its way into the city ended on January 4, 1942, in a painful retreat. Chinese army and guerrilla units harassed the exhausted, half-starved Japanese during their escape 100 miles/161 km north to Yochow (Yueyang). Third Changsha had been another debacle for the enemy, while Chiang’s forces, prestige, and position as the head of the KMT were all strengthened. The boost in fortunes spilled over to the Western Allies (Americans, British, and Australians) as well, stung at the moment by their losses in the Pacific. In Chiang and his National Revolutionary Army the Allies saw a partner who could now be taken more seriously and whose involvement in the China-Burma-India Theater could and should be stoked.

China vs. Japan: The Four Battles of Changsha, 1939–1944

|

Above: By the early 1900s the 3,000-year-old fortified city of Changsha had emerged as an important commercial, mining (tungsten), manufacturing, and transportation center (road, river, and 2 major railroads) in south-central China and was home to a significant number of expatriates after Changsha was opened to foreign trade in 1904. On-site Japanese military leaders believed that the capture of Changsha, with its surrounding districts (goldenrod in map), was key to pacifying Hunan Province (light gray area), which in turn was critical to the Chinese Nationalist war effort. Only after attacking the city on their fourth try in mid-1944 did the Japanese succeed in their aims. The successful 47‑day operation involved 360,000 Japanese troops—more troops than any other Japanese campaign in the war—arranged against 300,000 Nationalist defenders. At this point, though, the tide of war was turning inexorably against the Japanese, both on the Asian mainland and in the Pacific. Japan’s offensive power was history.

|  |

Left: This photograph shows the Japanese army forcing its way into Changsha on September 27 or 28, 1941, during the Second Battle of Changsha (September 6 to October 8, 1941). The Japanese offensive was carried out by more than 120,000 troops supported by naval and air forces. Chinese defenders numbered 300,000 and were in possession of nearly twice as many artillery pieces. After heavy fighting on the 28th, the Japanese began a general retreat, suffering 13,000 casualties (Japanese source) or 48,000 casualties (Chinese source). A little over a year later Japanese forces paid a third visit to Changsha, suffering just over 6,000 casualties (Japanese source) or 56,000 casualties (Chinese source).

![]()

Right: Behind brick walls and sandbags Japanese troops fend off a Chinese counterattack during 1 of the 4 battles of Changsha.

|  |

Left: A Japanese soldier fires a Type 92 heavy machine gun across the Milo (Miluo) River north of Changsha on September 22 or 23, 1941, less than a week before the Japanese army entered the city (Second Battle of Changsha). The relatively slow-firing 7.7 mm/0.303 in., air-cooled Type 92 typically required a 3‑man team and was the standard Japanese heavy machine gun used in World War II. Captured Type 92s were also used extensively by Chinese troops.

![]()

Right: A Chinese soldier mounts his Czechoslovak-designed ZB vz. 26 (ZB‑26) light machine gun at Changsha, January 1942. Chinese soldiers were the main users of this gas-operated, air-cooled machine gun in World War II. Though more than 30,000 ZB‑26s were exported to China between 1927 and 1939, due to high demand Chinese small-arms factories were producing the gun as well.

Japanese Expansionism in Asia During the 1930s and 1940s

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click