JAPANESE CARRIERS SET OUT FOR PEARL HARBOR

Hitokappu Bay, Kurile Islands, Northern Japan • November 26, 1941

For several months the airmen of Japan’s First Naval Air Fleet had trained for an attack on the main base of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. Squadrons of naval planes flew low over the city of Kagoshima on the southwestern tip of the Japanese island of Kyūshū—Kagoshima lay in the shadow of the Sakurajima volcano—making dummy runs against target vessels in the bay. Fifty-seven-year-old Adm. Isoruku Yamamoto, since 1939 commander-in-chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet (Rengō Kantai), had chosen Kagoshima for its topographical similarity to Oahu.

Now on this date, November 26, 1941, all 6 of Japan’s first-line aircraft carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Hiryū, and Sōryū—steamed into history when they left the Japanese Kurile Islands (annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945) under the command of 54‑year-old Vice Adm. Chūichi Nagumo. With 441 embarked planes, the flattops constituted the then most powerful carrier task force ever assembled. (By October 1944 all 6 enemy flattops lay on the ocean bottom, courtesy of the U.S. Navy.) The Japanese Pearl Harbor Striking Force (Kidō Butai) also included 2 fast battleships, 3 cruisers, 9 destroyers, 23 submarines, and 4 midget submarines, with 8 tankers to fuel the ships during their passage along a seldom-used route of the Pacific Ocean.

The Pearl Harbor Striking Force was positioning itself to carry out the surprise attack when, on December 2, it received the fateful signal (“Climb Mount Niitaka”) to bomb Pearl Harbor, which its carrier planes did on December 7, 1941, a date which, President Franklin D. Roosevelt told the U.S. Congress and the world the next day, “will live in infamy.” When Japanese Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) asked Chief of Army General Staff Hajime Sugiyama about Japan’s prospects in a war against the U.S., he was assured that the war would be over in 3 months. Hirohito shot back that Sugiyama’s estimated time frame for victory in the Sino-Japanese War, begun in 1937, never materialized. (Ten days after Japan’s surrender in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, Sugiyama committed suicide.)

In any event, the sneak attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet and nearby airfields (principally Ford Island Naval Air Station, Wheeler, and Hickam Fields) at Pearl Harbor was a stunning tactical victory for Japanese militarists. The master stroke removed 88 percent of the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s battleships (60 percent of the U.S. Navy’s capital ships) from combat service in a single morning. But the attack, wherein 21 ships were sunk or crippled (all but 3 of the ships were salvaged and returned to wartime service), 250 or so Army and Navy aircraft damaged or destroyed (mostly on the ground), and 3,500 individuals killed or wounded—tragic as it was—also spelled Hirohito’s and the militarists’ doom—as well as Adolf Hitler’s and Benito Mussolini’s, whose countries declared war against the United States 4 days later out of respect for their Tripartite Pact partner. In all 3 cases, the leaders of Imperialist Japan, Nazi Germany, and Fascist Italy grossly underestimated the capacity of the American people—grim faced and determined—to avenge themselves on those who had brought an unprovoked war to their shores.

Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941

|

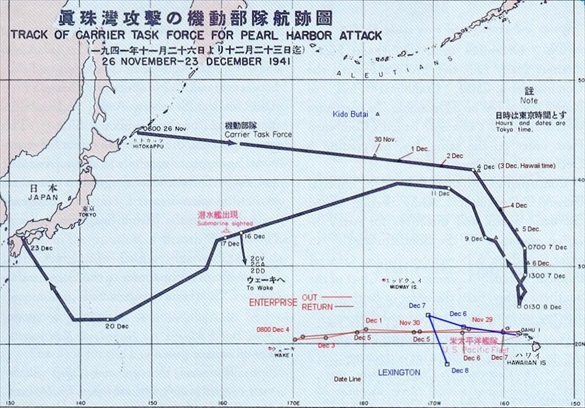

Above: This postwar U.S. map is derived from an original Japanese map that uses Tokyo time to chart the movement of the Japanese Pearl Harbor Striking Force to and from Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (bold black). The Japanese strike force set out on November 26 (November 25 in the U.S.) before the Roosevelt administration and Japanese envoys in Washington, D.C., had concluded their discussions on avoiding war. Depicted later on the original Japanese map are the routes of U.S. aircraft carriers Enterprise (red) and Lexington (blue) in early December to the west of the Hawaiian Islands (right bottom corner). Had the 2 American carriers been caught in Japanese crosshairs north of the Hawaiian Islands, their resting place might have been in waters too deep for salvage operations.

|  |

Left: In January 1941 Adm. Isoruku Yamamoto (1884–1943), a recognized leading expert in military aviation, outlined a surprise attack plan similar to that of the Royal Navy’s spectacular November 11/12, 1940, all-aircraft, ship-to-ship naval attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, Italy. Taranto was the first ship-to-ship naval attack in history. Though Yamamoto played no part in Japan’s decision to go to war with the U.S. and indeed admired America—he briefly studied at Harvard University, was a proficient English speaker, and spent 2 years in Washington as a naval attaché—he believed only a preemptive strike on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor could win the time his country needed to take over the rich mineral resources of British Malaya, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies (especially its oilfields in what is today’s Indonesia), and the U.S. Philippines. All these foreign holdings now found themselves inside Japan’s so-called Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, unilaterally launched on June 29, 1940. Faced with a military “fait accompli,” the U.S. might, Yamamoto hoped with crossed fingers, accept a truce in the Pacific War, adding, “the outcome must be decided on the first day.” In April 1941 Yamamoto ordered plans drawn up for “Operation Z,” the combined air and naval attack on Pearl Harbor, confiding to a staff officer, “If we fail, we’d better give up the war.” As payback for Japan’s December 7, 1941, sneak attack, Adm. Chester Nimitz, U.S. commander in the Pacific, authorized the aerial operation (Operation Vengeance) that shot down Yamamoto’s twin-engine G4M Betty naval bomber over the Japanese-held island of Bougainville in the South Pacific on April 18, 1943.

![]()

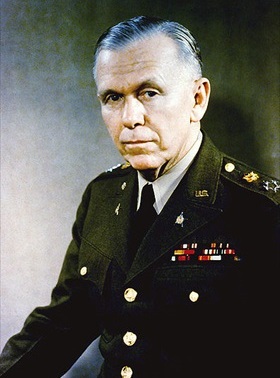

Right: George Marshall (1880–1959), Chief of Staff of the Army since September 1939, had visited Oahu in 1940 and considered Hawaii “the strongest fortress in the world.” In May 1941 he reported to President Roosevelt that “enemy carriers and escorts and transports will begin to come under air attack at a distance of 750 miles,” or 1,207 km, should it come to that. He concluded that “a major attack against Oahu is considered impractical.”

|  |

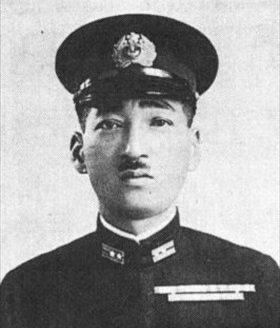

Left: On April 10, 1941, Vice Adm. Chūichi Nagumo (1887–1944) was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the First Air Fleet (Daiichi Kōkū Kantai), the Japanese Navy’s main aircraft carrier force, largely owing to his seniority. Fifty-three, heavy-set, and gray-haired, Nagumo had graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1908. A strong advocate of combining sea and air power but a cautious man, Nagumo was opposed to Adm. Yamamoto’s plan to attack the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor. Nagumo’s greatest mistake on that fateful Sunday morning in December, as Yamamoto later recalled, was not to order a third strike by his carrier planes, which might have destroyed not only the fuel oil storage and repair facilities, thereby rendering the most important U.S. naval base in the Pacific useless, but the submarine base and intelligence station. Nagumo’s missing these targets of opportunities contributed to his nation’s eventual defeat.

![]()

Right: Mitsuo Fuchida (1902–1976) was a Japanese captain in the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service and a bomber aviator in the Japanese Navy before and during World War II. Fuchida reported to his superiors in Tokyo on the devastation British torpedo bombers, launched from the HMS Illustrious in the Ionian Sea some 170 miles/273 km off the southern Italian coast, inflicted on Italy’s battle fleet riding at anchor in the safety of Taranto harbor on November 11/12, 1940. Fuchida is best known for leading the first air wave attacks on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, famously breaking radio silence with the code phrase for the surprise attack “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!). Working under Vice Adm. Nagumo, Fuchida was responsible for coordinating the entire aerial strike of fighter aircraft and high-altitude, dive, and torpedo bombers from all 6 Japanese flattops. He missed being killed or wounded by 1 day when the atomic mushroom cloud destroyed Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. In 1949 he converted to Christianity, became a missionary, moved to the U.S., and met many of his former enemies, including ex-President Harry S. Truman, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Admirals Chester W. Nimitz, William Halsey, and Raymond Spruance.

Japanese and U.S. Naval Preparations on Eve of December 7, 1941

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click