JAPANESE CARRIER FORCE HEADS TO MIDWAY FOR EPIC SHOWDOWN

Hashirajima Anchoring Area, Hiroshima Bay, Japan • May 27, 1942

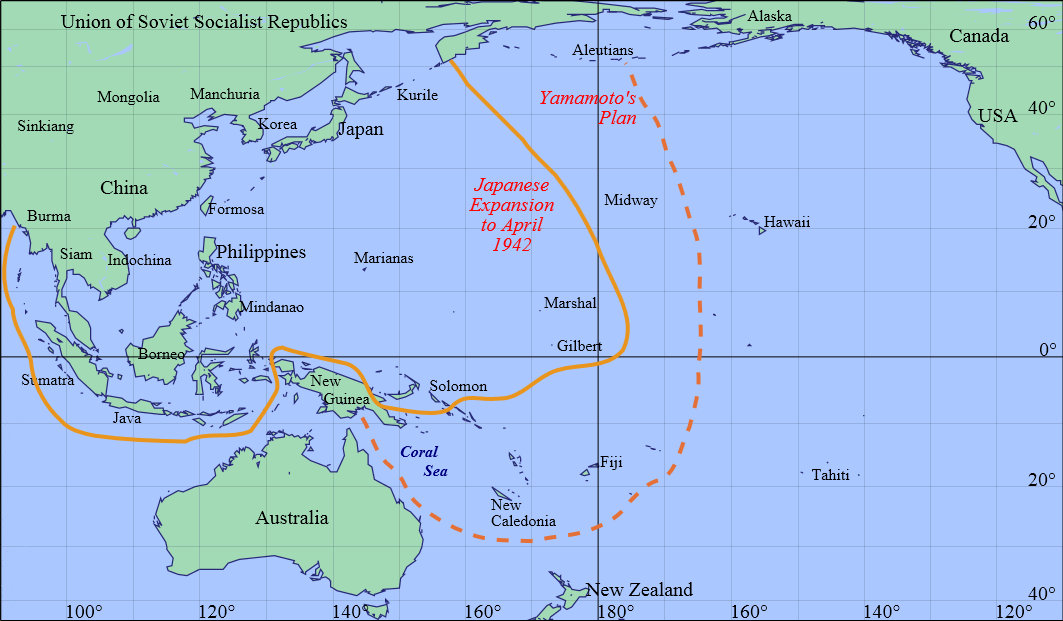

A little over 4 months after Japan devastated the U.S. Pacific Fleet riding at peaceful anchor at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Japanese Shōwa Emperor Hirohito and his Army and Navy staff officers received a rude calling card from Lt. Col. James “Jimmy” Doolittle and 79 other airmen of the United States Army Air Forces. The April 18, 1942, bombing of Tokyo by 16 B‑25 Mitchell medium bombers, which lifted off the aircraft carrier USS Hornet in the Central Pacific, was retaliation for Japan’s December 7, 1941, sneak attack. Though the Doolittle raid caused negligible material damage to the Japanese capital, it achieved its goal of raising American morale and casting doubt in the minds of Japan’s military leaders as to their ability to defend their home islands from more serious air raids. It also contributed to Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto’s decision to attack the U.S. outpost on Midway Atoll, the outermost island in the Hawaiian archipelago in the Central Pacific. As Japanese Marshal Admiral of the Navy and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during much of World War II, Yamamoto (1884–1943) intended to draw U.S. aircraft carriers, which were missing from Pearl Harbor on that fateful December morning, to the island atoll, destroy the U.S. Navy’s fighting ability in a “decisive battle” (kantai kessen), occupy Midway and push Japan’s Pacific Ocean defense perimeter hundreds of miles/kilometers to the east and south to prevent a repeat attack on the Home Islands (see map below), and, best case scenario, force the U.S. to withdraw from the Pacific War.

On this date, May 27, 1942, less than 3 weeks after the first major naval battle of the Pacific War—the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942), a Japanese tactical victory—Yamamoto hastily dispatched a powerful Japanese strike force (71 major warships) to Midway Atoll and a second, diversionary fleet to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. U.S. Adm. Raymond Spruance’s Task Force 16, with fleet carriers USS Enterprise and Hornet, and Adm. Frank Fletcher’s Task Force 17, with the patched-up flattop Yorktown, all together one less fleet carrier than Yamamoto had, met the Japanese strike force on June 4 northeast of Midway without being detected. The 3‑day engagement inflicted irreparable damage on the Japanese carrier force: 3 fleet carriers (Kaga, Sōryū, and Akagi), their upper hanger decks covered with armed and fueled aircraft being prepared for air strikes against the American carriers, burst into flames and foundered after U.S. dive bombers dropped bomb after bomb after bomb on their floating targets. The remaining Japanese carrier, Hiryū, was mortally wounded soon afterward at the price of the main U.S. casualty, the valuable carrier Yorktown, struck by 2 of Hiryū’s aircraft-launched torpedoes.

The Battle of Midway was the first clear-cut victory for the U.S. in World War II and the first naval defeat for Japan since 1870. Yamamoto, ill with diarrhea on board the super battleship Yamato, watched over the loss of two-thirds of Japan’s fleet carriers, 332 aircraft, and 3,500 men, including hundreds of irreplaceable pilots. On the American side, 1 fleet carrier (Yorktown), 1 destroyer (Hammann), about 150 aircraft, and 307 lives (mostly aviators) were lost. The American toll could have been much higher except for U.S. JN‑25B code breakers who knew that Yamamoto was planning a trap at Midway for the U.S. Pacific fleet. The code breakers even knew Yamamoto’s order of battle. Yamamoto’s trap (at best a crapshoot) backfired: from that point on the Imperial Japanese Navy lost all momentum in the Western Pacific and remained on the defensive for the remainder of the war. Japan’s decelerating naval hegemony expedited America’s successful island-hopping campaign, starting with Guadalcanal in the Solomons in August 1942, that took the Allies to the shores of the Japanese Home Islands in June 1945.

Naval Battle of Midway, June 4–7, 1942, America’s First Major Victory Against the Japanese and a Devastating Defeat for Japan

|

Above: In 1938 Midway Atoll was identified as second only to Pearl Harbor in importance to American security in the Pacific Ocean area. Operation MI, the Japanese operation against Midway (June 4–7, 1942), like the attack 7 months earlier on Pearl Harbor 1,100 miles/1,770 to the southeast, sought to eliminate the United States as a strategic power in the Pacific. Doing so would, on the one hand, give Japan the freedom to expand its enormous economic and cultural sphere, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (launched June 29, 1940), comprising Japan, Manchukuo (Manchuria), Korea, the island of Formosa (Taiwan), parts of China, and parts of Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific, and on the other hand provide the country with Lebensraum (German, “living space”) to settle its surplus population. (1939 population of 71.9 million inhabitants occupied 147,116 sq. miles/381,000 sq. kilometers spread unevenly over 4 major mostly mountainous “home” islands the area of California.) The Japanese hoped another demoralizing defeat post-Pearl Harbor would force the U.S. to capitulate in the Pacific War on Tokyo’s terms and thus acknowledge Japanese military, commercial, and ethnic dominance in an even greater part of the Pacific Ocean basin. Luring the American aircraft carriers into a trap and occupying the U.S. Midway outpost was part of Adm. Yamamoto’s “barrier” strategy to extend the Empire’s defensive perimeter to the east and south in the aftermath of Jimmy Doolittle’s humiliating flattop air raid on the Japanese capital. The Midway aerial and amphibious operation was also considered preparatory for further attacks against Fiji, Samoa, the U.S. Hawaiian Islands, and possibly the U.S. West Coast.

|  |

Left: USS Yorktown (CV-5) is hit amidships by a Japanese aerial torpedo during the mid-afternoon attack by planes from the carrier Hiryū on June 4, 1942. In this photograph the Yorktown is heeling to port after receiving the second of the 2 torpedo hits that caused serious flooding. Note the heavy antiaircraft fire. The month before the U.S. flattop had been damaged and nearly capsized during the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942), Japan’s failed attempt to capture Port Moresby on the southwestern tip of the large island of New Guinea, which lay well within striking distance of Australia. The Yorktown was patched up at Pearl Harbor inside 72 hours and returned to duty on May 30 for its last tour as it turned out. Less than a year later, in April 1943, a second Yorktown flattop (CV‑10) was commissioned and participated in several campaigns during the Pacific War.

![]()

Right: The smoldering hulk of the 13,668-ton heavy cruiser Mikuma, its midships structure shattered, after carrier planes from the USS Enterprise and Hornet had pummeled it mercilessly (she was dead in the water by then) on June 6, 1942. As evidence of U.S. naval might, this photo was reprinted in U.S. publications throughout the war. Mikuma sank that night, losing 700 crewmen.

|  |

Left: Eleven of 14 Douglas TBD-Devastators of Navy Torpedo Squadron Six (VT‑6) are seen here being prepared for launching off the USS Enterprise’s flight deck on the morning of June 4, 1942. Three more of these slow, underarmed TBDs and 10 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter escorts were later pushed into position before launching could begin. Ten of the VT‑6 aircraft were lost attacking the Japanese fleet more than 2 hours later. The heavy cruiser USS Pensacola is in the right distance and a destroyer is in plane-guard position at left.

![]()

Right: The burning Japanese aircraft carrier Hiryū photographed from a Yokosuka B4Y biplane carrier torpedo bomber shortly after sunrise on June 5, 1942. The day before, the Hiryū had evaded destruction from Midway-based U.S. Army Air Forces 4‑engine Boeing B‑17 Flying Fortresses and U.S. Marine and Navy single-engine dive bombers. In this photo the below-deck forward hangar lies exposed due to the collapsed flight deck following a tremendous explosion on the hangar deck below. The Japanese scuttled the Hiryū a few hours later. Yamamoto cancelled the failed Midway operation after decisively losing the offensive initiative in the Pacific for his emperor.

The Battle of Midway Documentary

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click