JAPANESE BALLOON BOMBS STRIKE U.S. WEST COAST

Seattle, Washington • November 3, 1944

On this date in 1944 Japan began an explosive balloon campaign against the U.S. and Canada. The date was chosen to commemorate the birthday of former Emperor Meiji (1852–1912). Over the next 5 months the Special Balloon Regiment of the Japanese Army launched some 6,000 to 9,300 (sources vary) hydrogen-filled rubberized-silk or paper “fire balloons” (fūsen bakudan, lit. “balloon bomb”), or Fu-Gu’s, from the east coast of Honshū Island. (“Fugu” is the name for the poisonous puffer fish.) Made mostly by schoolgirls and carried across the Pacific by the high-altitude jet stream, the 32.8‑ft/10 m diameter “secret weapons” carried a container of magnesium flash powder, 4 small incendiary bombs, and a 33‑lb/15‑kg high-explosive antipersonnel bomb designed to spread shrapnel up to 300 ft/91 m away.

Crude but ingenious, building a balloon that carried 1,000 lb/454 kg of gear and that could survive a 3‑day or longer, 5,000‑mile/8,047‑km trip across the Pacific Ocean, then automatically drop its payload was technically challenging. A hydrogen balloon expands when warmed by the sunlight and rises, then contracts when cooled at night and falls. Japanese engineers devised a control system driven by an altimeter that discarded ballast (sandbags) or vented hydrogen to maintain altitude (30,000–38,000 ft/9,144–11,582 m).

Some 285 to 300 Japanese fire balloons reportedly reached the North American continent, some floating inland as far as Michigan. Most of the fire balloons fell harmlessly into the Pacific Ocean or self-destructed before reaching the mainland. However, pieces of paper from a Japanese fire balloon were found on a Los Angeles street. When the balloons were sighted near the U.S. West Coast or over land, aircraft from the U.S. Navy or U.S. Army Air Forces flew intercept missions to shoot them down.

The only known fatalities of one of these devices were 6 Saturday afternoon picnickers who were killed near Bly, Klamath County, in southern Oregon, on May 5, 1945, when they tried to move a downed balloon and the antipersonnel mine exploded. An explosion from another balloon bomb took down power lines to the Manhattan Project’s Hanford, Washington, atomic processing facility, triggering a brush fire and ironically briefly shutting down work on the production of material for the atomic bomb that was later dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. (A backup power source averted what might have been a serious nuclear incident.) Wildfires caused by the balloons’ incendiary bombs presented a graver danger to the public than their antipersonnel mines, and 1 fatality and 22 injuries were recorded by firefighters.

Following two news media accounts in early January 1945 of a “balloon mystery,” the U.S. Office of Censorship and its Canadian counterparts enforced a news blackout on the subject. The blackout was intended to reduce the chance of panic among residents in the western U.S. and Canada and to deny the Japanese any information on the success of their launches, initially thought to have been launched by landing parties from Japanese submarines. Discouraged by the apparent failure of their effort, the Japanese halted their balloon bomb offensive in April 1945, when the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean lost its velocity and hydrogen supplies in Japan evaporated. Only after the war did Japanese authorities learn that some of their deadly balloons had, in fact, made their way to North America.

Japan’s Fire Balloon Campaign and Other West Coast Attacks

|  |

Left: A Japanese balloon bomb reportedly discovered and photographed by the U.S. Navy in Japan. Large indoor spaces such as sumo halls, sound stages, theaters, and aircraft hangers were required for balloon assembly. The firebombing of Japanese cities by U.S. B‑29 4‑engine bombers destroyed 2 of the 3 hydrogen plants needed by the project. Despite the initial high hopes of their designers, the Japanese fire balloon campaign was totally ineffective and survives in memory only as an ingenious curiosity.

![]()

Right: A Japanese fire balloon of mulberry paper (“washi”) re-inflated at the naval air station, Moffett Field, California, after it had been shot down by a U.S. Navy plane on January 10, 1945. The balloon is now owned by the National Air and Space Museum. Fire balloons were the first-ever weapon capable of intercontinental range (a record not broken for decades), and their envelopes and apparatus were found on the U.S. West Coast (Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California); in the Mountain states (Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado); and in the Midwest (Texas, Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Michigan, and Iowa). A few balloons landed in Mexico and Canada (Manitoba, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, and the Yukon).

|  |

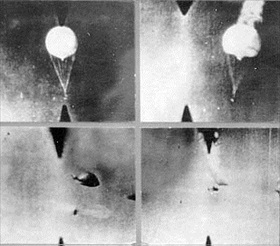

Left: Gun cameras capture Japanese fire balloons being shot down by a Lockheed P‑38 Lightning near Attu in Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain, April 11, 1945. Fire balloons flew very high and surprisingly fast, and U.S. aircraft destroyed fewer than 20. Between 285 and 300 fire balloons reportedly landed in the U.S. Oregon recorded the most incidents, 45. British Columbia recorded 57. The last balloon found was in Alaska in 1955, its payload still lethal after 10 years. Japanese wartime propaganda announced fire balloons had wreaked havoc to forests, cities, and farmland, inflicted casualties as high as 10,000, and described an American public in panic. The truth was, the 6 picnickers killed in Oregon (1 pregnant woman and 5 children) and 1 firefighter were the only fatalities caused by Japan’s fire balloon campaign.

![]()

Right: The Japanese performed a small number of non-balloon attacks on the U.S. mainland throughout the war. In February 1942 Japanese submarine I‑17 shelled an oil field up the beach from Santa Barbara, California, and damaged a pump house. Later that June submarine I‑25 shelled a coastal fort, Fort Stevens in Oregon, churning up a swamp and a baseball field (photo shows soldiers inspecting the shell crater). Twice in September I‑25’s crew assembled and launched a small floatplane that dropped a total of 4 incendiary bombs, again in Oregon, starting a few small forest fires. U.S. Forest Service personnel investigated the origin of the fires, thinking they had been caused by lightning; however, at the scene they found a crater, shrapnel, and the bomb’s nose cone with Japanese markings. The bombing is notable for being the only aerial bombardment of the contiguous United States by an Axis power.

Japanese Balloon Bombs Land in U.S. and Canada, November 1944 to April 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click