JAPANESE AMERICAN VIOLATED MILITARY ORDER

San Leandro, California · May 30, 1942

On this date in California in 1942, California-born Japanese American Fred Korematsu was arrested for refusing to comply with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War and his military commanders to require all Japanese Americans be removed from designated “military areas” and placed in internment camps in the U.S. interior. When orders were issued on May 3, 1942, for Japanese Americans to report on May 9 to assembly centers as a prelude to their being sent to internment camps, Korematsu, a trained shipyard welder, became a fugitive. He underwent plastic surgery on his eyelids in the hope of passing as a Caucasian, changed his name to Clyde Sarah, and claimed to be of Hawaiian-Spanish heritage. He was arrested in San Leandro near Oakland, California, after being recognized as a “Jap.”

Korematsu’s conviction for disobeying a military order issued under the authority of Executive Order 9066 led to a test of the order’s legality before the U.S. Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States. On December 18, 1944, in a 6–3 decision, the High Court ruled that “compulsory exclusion,” meaning internment, though constitutionally suspect, was justified during circumstances of “emergency and peril.” Yet after the war the order remained on the books.

Decades later Korematsu’s conviction was overturned after new evidence challenged the need for the internment. On February 19, 1976, President Gerald Ford rescinded Executive Order 9066. “We now know what we should have known then,” he said, “that evacuation [was] wrong.”

Ford’s successor, Jimmy Carter, signed legislation in 1980 to create a Congressional commission to conduct an in-depth study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders, and their impact on Japanese Americans and native Alaskans. In December 1982 the commission issued its findings in Personal Justice Denied, concluding that the incarceration of Japanese Americans, almost half of whom were children, had not been justified by military necessity and recommended an official government apology and redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors. Congress passed and President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 to ensure that the injustice inflicted on Japanese Americans during World War II would never happen to any group again.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1890771309,0700619267,1410927121,0809078961,0939165538,0295974842,1470168162,0295992700,1890771910,1893343057″ /]

Compulsory Japanese Relocation and Internment

|  |

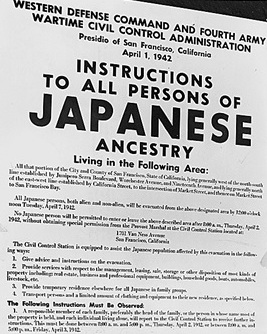

Left: Sign posted in San Francisco notifying people of Japanese ancestry to report for mandatory relocation. (Information on the ultimate destination and length of stay in a relocation center was not made available.) Approximately 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans (62 percent of whom were U.S. citizens) from the U.S. West Coast were affected by Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. While roughly 10,000 were able to relocate to other parts of the country of their own choosing, the remainder—some 110,000 men, women, and children—were crammed into primitive, hastily constructed camps called “War Relocation Centers” in remote parts of the nation’s interior.

![]()

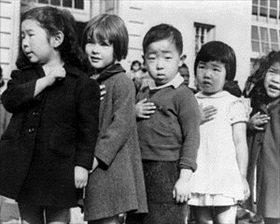

Right: San Francisco, California, first-graders, some of Japanese ancestry, pledge allegiance to the U.S. flag, April 1942. The evacuees of Japanese ancestry would soon be interned in War Relocation Authority (WRA) centers for the duration of the war (1942–1945). Internees were put to work building, among other things, dams, canals, roads, school classrooms, baseball fields, basketball courts, and parks. At the Granada Relocation Center (Camp Amache) in Southeastern Colorado (peak population 7,318 persons in February 1943), internees in the silkscreen shop produced propaganda posters for the U.S. Navy. About 6,000 babies were born in the internment camps.

|  |

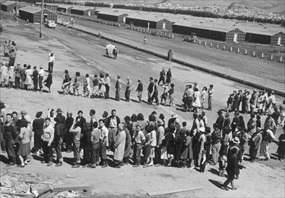

Left: This assembly center in San Bruno, California, just south of San Francisco, had only been open for two days when Dorothea Lang, on assignment with the WRA, snapped this photograph on April 29, 1942. Busload after busload of evacuated persons of Japanese ancestry were arriving that day, going through the necessary procedures for registration. Afterwards the families were guided to the newly built barracks in the background, to be bused later to permanent relocation centers like Manzanar. Evacuees were forced to leave homes, businesses, possessions, and pets behind, taking only what they could carry.

![]()

Right: Manzanar, located at the foot of the Sierra Nevadas in California’s Owens Valley, was the first of ten permanent internment camps where over 110,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated. Lange visited Manzanar in July 1942 and recorded the internees’ plight and deprivation in a remarkable collection of photographs. This one is of a mess hall and a row of barracks looking west to the desert beyond, with the Sierra Nevadas in the background. On this day, July 3, a hot windstorm blanketed the camp with dust from the surrounding desert. At its peak Manzanar held 10,046 internees. In all, 11,070 people were “relocated” to Manzanar, 90 percent drawn from the Los Angeles area. Today, Manzanar is designated a National Historical Site (part of the U.S. National Park Service) and is visited by fewer than 85,000 people a year (2015).

|  |

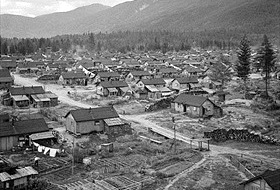

Left: Unnamed internment camp for Japanese Canadians in British Columbia, June 1945. There were ten Japanese internment camps in Canada. Over 75 percent of the 20,881 Japanese and Japanese Canadians who were uprooted and interned in Canada in 1942 were Canadian citizens. The camps were euphemistically called “Self-Supporting Centers.” Some internment camps in British Columbia were in a mountainous area so physically isolated that fences and guards were not required because the only way in or out was by rail or water. Those who resisted their removal were shipped further east to POW camps in Ontario, Central Canada.

![]()

Right: In 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed legislation that apologized on behalf of the U.S. government for wartime Japanese American internment. The legislation stated that government actions at the time were based, not on “military necessity,” but on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Starting in 1990 the U.S. government paid reparations to surviving internees. Cost to the U.S. Treasury: $1.6 billion.

Wartime American Propaganda Film Justifying the Internment of Japanese Americans and Japanese Aliens

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click