JAPAN: WAR INEVITABLE WITHOUT U.S. CONCESSIONS

Tokyo, Japan • September 6, 1941

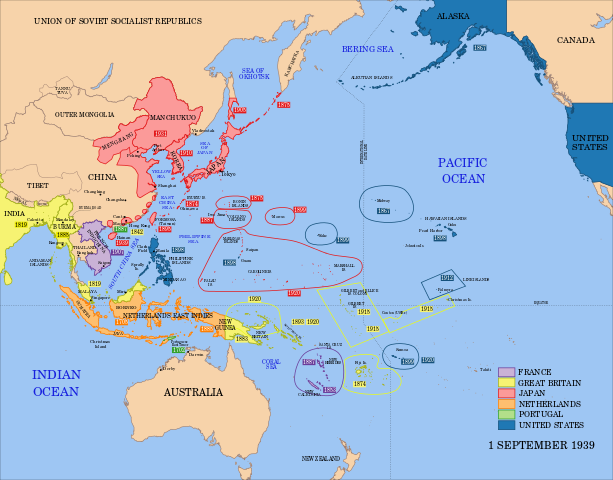

On this date in 1941, in an Imperial Conference in Tokyo, Japanese military and political leaders embarked on a collision course with the West. It was decided that Japan would begin war preparations against the U.S., Great Britain, and the Netherlands (all countries with territorial claims in Southeast Asia; see map below) while simultaneously continuing its diplomatic efforts in Western capitals—to unleash hostilities should diplomacy fail to lift onerous sanctions imposed by the West the previous July and August in retaliation for Japan’s seizure of French Indochina (present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos). The U.S., for example, froze all Japanese assets in the country, closed the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping, and forbade all export trade with Japan. (Japan quickly lost access to 93 percent of its oil imports.) Netherlands (Dutch) East Indies (present-day Indonesia) followed the U.S. lead with asset and oil export freezes. Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand likewise froze Japanese assets, while Great Britain went further by announcing its intention to end bilateral commerce.

A resolution the day before, that is, on September 5, 1941, by Japan’s Supreme War Council favoring war with the West only awaited Shōwa Emperor Hirohito’s ceremonial sanction (ratification) at the Imperial Conference before it became state policy. At both assemblies, those of September 5 and 6, Hirohito expressed his desire to give diplomatic negotiations priority over a military solution. However, the pre-made decision by the Army and Naval General Staffs at the Supreme War Council on September 5 easily passed muster the next day at the Imperial Conference, which was not a real deliberative body. An October 10 deadline was set to begin war preparations.

Between the September 6 Imperial Conference, the October 10 deadline, and the appointment of hardline pro-war War Minister Army Gen. Hideki Tōjō to the post of prime minister on October 17, 1941, the supreme command worked overtime to press the emperor to embrace its view on the inevitability of war with the West despite his wish for peace. An October 20 report released for the Army General Staff to use in pressing their hawkish views on Hirohito depicted how a war with the West was winnable even if it dragged on for several years. More memos followed and more meetings between Hirohito and his military and civilian advisers occurred. By November 20, when the Roosevelt administration rejected Prime Minister Tōjō’s final proposal for peace in the Asia Pacific area and countered with its own peace proposal (totally unacceptable to Japan’s pro-war leaders) on November 26, Hirohito had already wavered from his pacifist leanings to the point where he was in agreement with the hawks. In a December 1 Imperial Conference Hirohito formalized Japan’s decision to attack Western interests beginning on December 7 and 8, 1941. Japan would call this war against Western interests the Greater East Asia War (Dai Tō-A Sensō), a name that was used in public for the first time on December 12, 1941. The term embraced both the ongoing war with China and the newly declared war against the West.

U.S.-Japanese Relations on the Eve of the Pacific War

|

Above: Political map of Japanese, European, and U.S. possessions in the Asia Pacific region on the eve of hostilities. Japanese control on mainland China (rose colored) was tenuous.

|  |

Left: Japanese Ambassador Adm. Kichisaburō Nomura and Special Envoy Saburō Kurusu with U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull (middle), November 17, 1941. The 2 diplomats presented Japan’s final peace proposal for the Asia Pacific region to the Roosevelt administration on November 20. (Nomura had presented an earlier peace proposal on November 6, but the U.S. rejected it on November 14). Recognizing the chance of success was slim, Emperor Hirohito nonetheless pinned his hopes on this last final push to break the diplomatic stalemate in Washington. Japan demanded that the U.S. give it a free hand in China; discontinue aiding Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalists; recognize Japan’s puppet government in Northeast China, Manchukuo; recognize the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan’s self-sufficient economic-military sphere in occupied Asian territories; and undo trade embargoes and financial freezes directed against the country.

![]()

Right: Nomura and Kurusu (tipping hat) after speaking with Secretary of State Cordell Hull and President Roosevelt at the White House, November 27, 1941. The Roosevelt administration’s final peace proposal (“Hull Note”) delivered on November 26 laid out the following counter conditions, among others: Japan and the U.S. will endeavor to conclude a multilateral nonaggression pact among states with a claim to territories in the Asia Pacific region, Japan must respect China’s territorial and political integrity (meaning the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek), respect free and open markets in China, and withdraw all military, naval, and police forces from China and Indochina before the U.S. would unfreeze Japanese financial assets and resume trade with Japan. A disappointed Hirohito construed the “Hull Note” as shutting down diplomatic negotiations between the 2 governments.

Contemporary Newsreels Document Japan’s Application of a “Free Hand” in China

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click