JAPAN TELLS SOLDIERS: “NEVER SURRENDER”

Tokyo, Japan • January 8, 1941

On this date in 1941 the Tokyo Gazette published the Imperial War Department’s newly adopted Japanese Field Service Code. It advised soldiers in part, “Do not give up under any circumstances, keeping in mind your responsibility not to tarnish the glorious history of the Imperial Army with its tradition of invincibility.” Japan had refused to ratify the 1929 Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war partly, as the country’s vice minister of the navy explained, because the Japanese had no concept of being captured. Additional disincentives to surrendering were the government’s warning that any Japanese POW returning home would be shot and the rumor that the Allies tortured and killed any prisoners they took.

Toward the end of the war in the battle for the Philippine capital of Manila (February 3 to March 3, 1945), 17,000 Japanese troops fought to maintain control of the city in vicious hand-to-hand fighting. More than 16,000 Japanese servicemen perished along with 1,000 Americans and 100,000 Filipinos. During the Battle for Manila U.S. troops also captured the small rock island fortress of Corregidor in the entrance to Manila Bay. Some 5,000 well-provisioned Japanese troops held out on Corregidor for 10 days, costing 225 American lives and 405 wounded. The Japanese dead numbered over 4,500. Of these 500 were buried alive by U.S. bulldozers or demolition charges, sealed in Corregidor’s caves from which they had been fighting. Indoctrinated to choose between victory and a heroic death, only 20 Japanese were taken captive.

On the island of Iwo Jima during this time frame, the Allies engaged 22,000 island defenders over the course of 5 weeks. Total Japanese dead was almost 19,000. Only 216 Japanese were taken prisoner (some captured because they had been knocked unconscious or were otherwise disabled); roughly 3,000 went into hiding. On the high seas, Allied submariners’ disinclination to rescuing shipwreck survivors, as much as Japanese resistance to being taken captive anywhere, goes a long way explaining why, at the end of the war in the Pacific, the U.S. held only about 5,500 Japanese POWs. Japan’s Axis partner Nazi Germany had nothing comparable to the Japanese Field Service Code, and thus the Allies held over 12 million German POWs and Disarmed Enemy Forces (so-called DEFs) during the war.

Japanese Prisoners of War in Allied POW Camps in the Pacific Theater

|  |

Left: The Battle of Manila lasted for 1 month, from February 3 to March 3, 1945. At the end, Japanese casualties largely amounted to the entire force of 10,000 sailors and marines and 4,000 soldiers, with only dozens surrendering, mostly foreigner laborers (perhaps these 2 men seen in this photograph).

![]()

Right: A group of Japanese prisoners of war on Okinawa, June 1945. The Battle of Okinawa (April 1 to June 22, 1945) was the first battle in the Pacific War in which thousands of Japanese soldiers surrendered or were captured. Many of the prisoners were native Okinawans who had been pressed into service shortly before the battle and were less imbued with the Japanese Army’s no-surrender doctrine. When the American forces occupied the island, many Japanese soldiers put on Okinawan clothing to avoid capture.

|  |

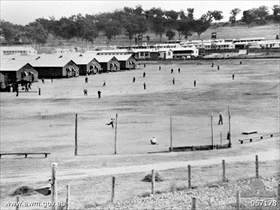

Left: Japanese POWs practice baseball near their quarters in Cowra, Australia, prior to August 5, 1944, when they staged a breakout that resulted in the deaths of 257 of their own and 4 Australian guards. The photograph was taken with the intention of using it in propaganda leaflets, to be dropped on Japanese-held areas in the Asia Pacific region. Tokyo lodged protests with the Australian and New Zealand governments, the only time the Japanese government officially recognized that some members of the country’s military had surrendered.

![]()

Right: A rope-tied Japanese soldier captured in mid-1945 at Balikpapan on the east coast of Borneo, the world’s third-largest island in today’s Indonesia, during Operation Oboe (May 1 to August 15, 1945). Heavy bombing and shelling by Australian and U.S. air and naval forces in July 1945 overwhelmed enemy outposts manned by roughly 30,000–31,000 Japanese Army regulars and conscripted locals on Borneo. As in other battles in the Pacific War many Japanese fought to the death. This Japanese soldier was an exception, perhaps caught as the Australians combed the jungles and hills for stragglers following the end of major operations on Borneo.

|  |

Left: A group of Japanese POWs in Northern Malaya, November 15, 1945. Japanese forces in Malaya surrendered to the Allies first at Penang on September 4, 1945, then, after Singapore’s surrender, in Malaya’s capital Kuala Lumpur on September 13, 1945. Japanese soldiers who remained in Malaya, Java, Sumatra, and Burma at the end of the war were transferred a few miles/kilometers across the straits from Singapore to the Indonesian islands of Rempang and Galang, where from October 1945 onward more than 200,000 Japanese troops awaited repatriation to Japan. The last troops left the islands in July 1946.

![]()

Right: In China, few Japanese soldiers surrendered to Chinese forces prior to August 1945. It has been estimated that at the end of the war Chinese Nationalist and Communist forces held around 8,300 Japanese prisoners. Following the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan on August 8, 1945, the Red Army captured 640,276 stranded Japanese in Manchuria. This photo shows Kwantung Army soldiers (Japan’s occupation army in China) being marched into Soviet captivity in Changchun (renamed Hsinking by the Japanese in 1932), the capital of their puppet state Manchukuo (Manchuria). After Japan’s surrender in September 1945, some 560,000 to 760,000 Japanese POWs were interned in the Soviet Union and Mongolia to work in labor camps. Between December 1941 and August 15, 1945, the date of Japan’s capitulation, the Western Allies had taken just 35,000 Japanese prisoners; most were repatriated by 1946. The Soviets held Japanese POWs much longer and used them as a labor force.

U.S. Navy Ensign Robert Russell’s Account of His 1,200 Days as a Japanese POW in the Philippines, Japan, and China (Part 2)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click