JAPAN TARGETED FOR STARVATION

Tinian, Mariana Islands · March 27, 1945

An island nation, Japan was vulnerable to a blockade of essential food and strategic materials. On this date in 1945 the U.S. Army Air Forces and the U.S. Navy, hoping to put the final nail in the enemy’s coffin, kicked off Operation Starvation, the aerial mining of Japanese waters. Three nights later 85 more “miners” followed suit. By beginning the nighttime aerial dropping of mines (eventually 12,000 mines) in rivers and coastal waters, Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay’s Marianas-based B‑29 Superfortresses accessed Japanese waters too shallow or close to land for Allied submarines to enforce a sea blockade. The five-month-long aerial campaign saw the near destruction of Japanese coastal shipping and shipping lanes, halting Japan’s importation of critical raw materials and food and forcing the abandonment of 35 of 47 vital convoy routes. Adding LeMay’s incendiary raids on urban and military-industrial areas to the destructive mix reduced Japan’s overall production in 1945 by two-thirds compared with the year before. Already in 1940 rice—the chief item in the Japanese diet—had been subject to rationing due to bad harvests in the Japanese colony of Korea and the demands of the Japanese military in China (since 1937) and Southeast Asia (since 1941). Fish, the other dietary staple, had all but ceased to be distributed in some areas in 1944. Food supplies were so meager that the average Japanese citizen was living at or near starvation level. Average civilian caloric intake in 1945 was 78 percent of the minimum needed for health and physical performance. By the end of June the civilian population began to show signs of panic. Experts predicted deaths by starvation would exceed seven million were Japan to somehow muster the will and resources to wage war through 1946. With the benefit of hindsight, Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945, was inevitable even without Hiroshima and Nagasaki, without Soviet entry into the war on August 8, 1945, and without the ghastly number of casualties projected by invading the Japanese island of Kyūshū in late 1945 and the main island of Honshū in April 1946 (Operation Downfall). But the horrors of the Pacific Islands campaign were so fixed in the minds of Allied leaders that the fire-and-sword strategy of using atomic weapons appeared to be the least costly way to bring World War II to an end.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0141001461,0230613969,1594160392,0143123017,1416584412,0760341222,0813141109,0786444584,0307275361,1570033544″ /]

Operation Starvation, March—August 1945

|  |

Left: B‑29 Superfortresses from Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay’s Twentieth Air Force fly near Mount Fuji, Japan, 1945. The name “Superfortress” was derived from that of the B‑29’s well-known predecessor, the B‑17 Flying Fortress.

![]()

Right: A U.S. Navy Seabee waves to B‑29 Superfortresses arriving at Tinian’s unfinished North Field in the Mariana Islands, 1944. The Marianas were about 1,500 miles from Tokyo, a range that the B‑29s could just about manage.

|  |

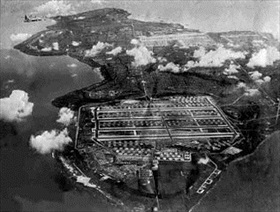

Left: Tinian after airfield construction, looking north to south, 1945. The massive North Field was home to the 313th Bombardment Wing, which consisted of four B‑29 Superfortress Bombardment Groups. Only one group was tasked with aerial mining Japanese harbors and waterways. The 313th Bombardment Wing later added the 509th Composite Group, which conducted the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

![]()

Right: 313th Bombardment Wing Headquarters, Tinian, 1945. About 160 aircraft of the 313th BW carried out Operation Starvation, flying 1,529 sorties on 46 separate missions. Operation Starvation sank or damaged more ship tonnage in the last six months of the war than the efforts of all other sources combined—670 ships totaling more than 1,250,000 tons.

“The Last Bomb,” a 1945 U.S. Army Air Forces Documentary on Bombing Japan

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click