JAPAN PROTESTS U.S. EMBARGO

Washington, D.C. · October 7, 1940

In the 1930s Japan’s statesmen and military leaders in China were acutely aware that their economy and armed forces were dependent on imports from the United States and its colonial friends who had holdings in the Asia Pacific region: the Americans in the Philippines, the British in Malaya (now Malaysia), the French in Indochina (now Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), and the Dutch in the East Indies (now Indonesia). The Japanese imported practically every domestic and industrial item they consumed or produced, much of it from a geographical area in which they felt they should dominate. Imports included most metals, rubber, and food, including rice. The U.S. supplied roughly 80 percent of Japan’s oil; the rest came from the oil-rich islands around the Java Sea—Borneo, Sumatra, and the Dutch East Indies. Washington clearly understood Japan’s utter dependence on oil and other overseas resources for its economic security. On this date in 1940 in Washington, D.C., Japan’s ambassador protested the U.S. embargo on aviation fuel and machine tools and the ban on the export of iron and steel scraps as an “unfriendly act.” The object of the embargoes (these and succeeding ones) served two purposes: to encourage the Japanese to halt military action in China, begun in 1937, and to assist the Chinese Nationalist army under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in waging war against the aggressor. The next day, October 8, the State Department advised U.S. citizens to leave the Far East “in view of abnormal conditions in those areas.” The State Department arranged for three passenger liners to sail to Yokohama and Kobe, Japan, as well as to Shanghai and Chinwangtao in China to repatriate Americans. A State Department employee wrote in his diary following the news that Japan had joined with Germany and Italy in the Tripartite Pact, which was a ten-year military and economic agreement signed on September 27, 1940, that Japan hoped to use it as a bargaining chip with America: “And so we go—more and more—farther and farther along the road to war. But we are not ready to fight any war now—to say nothing of a war on two oceans at once.” Ready or not, war came on December 7, 1941, with the most “unfriendly act” of all—the Japanese surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0801495296,0198221681,0842051538,0691145067,1597975346,0812968581,0823224724,1439183244,1846140102,1591145201″ /]

“Incidents” on the Chinese Road to World War II in the Pacific

|

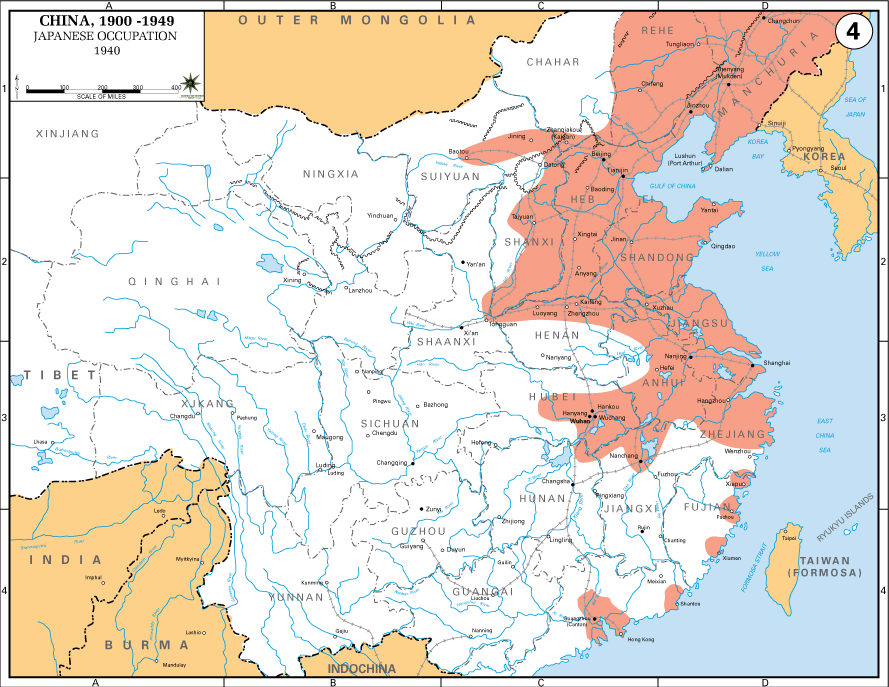

Above: Map of China, 1940, showing the extent of Japanese expansionism (in burgundy). Japan seized Taiwan in 1895, declared Korea an imperial protectorate in 1905, and invaded Manchuria (Manchukuo) in 1931.

|  |

Left: Japanese cavalry entering Mukden (Shenyang), Manchuria, September 18, 1931. Japan’s Kwantung Army on the Chinese mainland fabricated a bombing incident on a tiny portion of the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railway as a pretext to occupy Manchuria, a province semi-independent of China, and Northeast China. Both regions were rich in mineral and agricultural resources. Most Westerners believed the “Mukden Incident,” although coming on top of other Sino-Japanese incidents, was way overblown and should not have led to Japan’s takeover of Manchuria, where the Japanese installed a puppet government in a “state” they named Manchukuo.

![]()

Right: Manchukuo became the springboard for further Japanese aggression in China. Outlying provinces were annexed into Manchukuo or turned into buffer zones, effectively under Japanese occupation. By the start of 1937 all the areas north, east, and west of the large Chinese city of Beijing were controlled by Japan. On July 7–8, 1937, the Japanese provoked another “incident” at the eleven-arch granite Marco Polo bridge southwest of Beijing.

_1937_280x193.jpg) |  |

Above: The heightened tensions of the Marco Polo bridge incident led directly to Japan’s full-scale invasion of China in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), beginning with the Battle of Beijing-Tianjin (early July to early August 1937) and the Battle of Shanghai (August 13 to November 26, 1937). In the photo on the left Japanese troops are shown passing from Beijing into the Tartar City through Chen-men, the main gate leading to the palaces in the Forbidden City, sometime in mid-August 1937. In the photo on the right Japanese marines celebrate their successful landing near Shanghai that same month. Approximately 200,000 Chinese and 70,000 Japanese died during Japan’s three-month attempt to take Shanghai.

Japanese Aggression in China During the 1930s

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click