JAPAN CONSTRUCTS GIGANTIC I-400 SUB

Kure Navy Yard, Hiroshima Bay, Japan • April 25, 1943

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the architect of his country’s December 7, 1941, attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, envisioned a different fleet of Japanese aircraft and ships for a second round of attacks on American soil. It would be a bomber fleet of 2‑man floatplanes armed with bombs and torpedoes carried aboard and launched from stealthy submarines of mammoth size and operational range, off either west or east U.S. coasts. The construction of the first of an initially projected 18 underwater aircraft carriers formally began on this date, April 25, 1943, 1 week and a day after U.S. P‑38 Lightnings shot down the bomber transport carrying the admiral to the Pacific Island of Bougainville in Operation Vengeance, payback for Japan’s deadly attack in 1941.

Production delays and cutbacks in the wake of Yamamoto’s premature death meant that the I‑400 prototype submarine aircraft carrier was not commissioned until the end of 1944, 19 months later, followed quickly in early January 1945 by the I‑401’s commissioning. Though completed 7 months later, in mid‑July 1945, the I‑402 never put to sea (it was finished as a fuel tanker), bringing an end to the monster’s genetic line known as Sentoku, short for Sen-Toku-gata Sensuikan, which loosely translates to “Secret Attack (or Special Type) Submarine” in English. Just before the Pacific War ended I‑13 and I‑14, 2 smaller versions of the I‑400 class, known as Type AM submarines (also called I‑13‑class submarines) with the same aspirations as the bigger Sentokus, made a bow; however, not until nuclear submarines appeared in the 1960s did another submarine rival the size and operational range of the original I‑400 class.

In January 1945 4 underwater aircraft carriers were assigned to the Japanese 6th Fleet, 1st Submarine Flotilla. Crews learned how to handle the submarines and their floatplane bombers. After a yearlong intelligence gathering campaign, it was decided that the submarines’ first combat mission would be a surprise air strike on the canal locks in the American Panama Canal Zone, through which passed U.S. soldiers and equipment from the East Coast to the Pacific Theater. Intelligence estimated the 2‑ocean canal could be rendered unusable for up to 6 months were it attacked, and dry runs on a wooden model of the canal’s Gatun Locks gate were conducted in mid‑June 1945. The terminal phase of the war in the Pacific—the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands, which the Allies were calling Operation Downfall and which the warlords in Tokyo reckoned to start in August 1945—prompted a change in plans to instead focus on enemy targets closer to home. Ulithi Atoll, the huge American naval staging area in the Caroline Islands of the Western Pacific Ocean 1,300 miles/2,092 kilometers from the Japanese capital, was now the target of Japan’s Operation Arashi (Mountain Storm).

The deadly flotilla, comprising I‑400, I‑401, I‑13, and I‑14, departed Japanese waters in late July 1945 and slowly proceeded toward Ulithi. Leaving Ulithi’s anchorage over 3 months earlier, in March 1945 in the direction of Japan, was a huge convoy of U.S. Navy ships and personnel aboard 106 destroyers, 29 aircraft carriers, 15 battleships, and 23 cruisers. More warships would be departing. On August 16, Arashi flagship I‑401 received a radio message from 6th Fleet headquarters, informing the crew of their country’s surrender to the Allies the previous day and ordering the subs to return to base. All 6 Aichi M6A1 Seiran floatplanes on board I‑400 and I‑401 (I‑14 and I‑13 were carrying long-range reconnaissance aircraft), having been disguised for the operation as American planes in violation of the laws of war, were either pushed overboard (in the case of I‑400) or catapulted into the sea to prevent capture. Japan’s most radical flotilla of the war never dropped a bomb or fired a torpedo in combat.

Japan Builds I-400-Class Submarines to Bring War and Pandemonium to U.S. Mainland

|  |

Left: The mammoth Sentoku, or I‑400-class submarine. Difficult though it is, note the long water-tight, tube-like aircraft hangar on the sub’s aft deck and the forward deck’s compressed-air airplane catapult and collapsible crane for retrieving returning planes. Japanese plans called for building a fleet of 18 I‑400-class submarines, at 400 feet/122 meters in length and displacing 6,670 tons, by far the largest and among the most deadly subs ever built until the 1960s. (The U.S. Navy’s Balao-class submarines, the largest used during the war, were 88 feet/28 meters shorter.) Though Sentokus could fire torpedoes (8 on board) like other submarines, these super-subs were designed as underwater aircraft carriers, each equipped with 3 Aichi M6A1 Seiran floatplane bombers. Their mission was to travel more than halfway around the world (the I‑400 had a range of over 30,000 nautical miles/55,560 kilometers and carried a crew of 144 or close to 200 men), surface off American coastal cities, and launch deadly aerial attacks. The late-war I‑400-class “wonder weapon” was unknown to U.S. intelligence, despite having broken the Japanese naval code. All 3 I‑400-class subs were scuttled after having been studied by U.S. naval engineers: I‑400 and I‑401 were torpedoed as target ships near Oahu, Hawaii, on June 4 and May 31, 1946, respectively. I‑402 was scuttled off Nagasaki, Japan, on April 1, 1946.

![]()

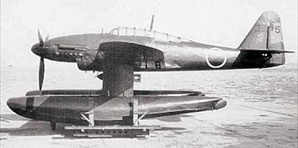

Right: A 2-man Aichi M6A1 Seiran floatplane, the type carried aboard the I‑400– and smaller I‑13‑class subs. The super submarines were designed to carry 2 (in the case of I‑13‑class subs) or 3 (I‑400-class) Seirans, a name that translates as “mist on a clear day” or “clear sky storm.” Each Seiran floatplane was capable of carrying 1 1,800‑pound/816 kilogram torpedo or the equivalent weight in bombs for up to 739 miles/1,189 kilometers. A well-trained crew of 4 men could roll a Seiran out of its watertight hangar on a collapsible catapult carriage, unfold the tail and wings pressed against the fuselage, and have it readied for flight in approximately 14½ minutes or twice that time if the plane’s pontoons were fitted. Twenty-eight Seirans, which included 8 prototypes used in testing, were completed by its manufacturer, Aichi, before production was halted due to the desperate shrinkage in the late-war size of the carrier submarine force. After a restoration that took 11 years, a solitary surviving M6A1 can be viewed in the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum located in Chantilly, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C.

|  |

Left: American naval personnel inspect I‑14, November 1945. Likely photographed near Sasebo Naval Arsenal, Japan, where she joined the company of I‑400 and I‑401. The Type AM (or I‑13-class) submarine was originally designed as a command submarine carrying reconnaissance floatplanes, but it was capable of carrying 2 Seirans. The large structure beneath the offset conning tower, clearly distinguishable in this photo, is the 11‑foot/3.35‑meter-wide cylindrical hangar that could hold 2 planes with folded wings and tail fin. The I‑14 was armed with 6 internal bow torpedo tubes and carried a total of a dozen torpedoes. The sub was also armed with a single 140‑millimeter/5.5‑inch deck gun and 1 single- and 2 triple-mount anti‑aircraft guns. The I‑14 carried enough fuel to sail around the globe 1½ times. Her sister ship, I‑13, was sunk on July 16, 1945, by a U.S. destroyer escort and carrier aircraft some 633 miles/1,018 kilometers east of the main Japanese island of Honshū. Flying the black flag of surrender, I‑14 surrendered at sea on August 27, 1945, 227 miles/365 kilometers northeast of Tokyo, and was scuttled in target practice off the Hawaiian island of Oahu on May 28, 1946.

![]()

Right: Sailors line the rails of the submarine tender USS Proteus, while other men crowd the forward deck of the I‑14 (center in photo), a smaller version of the I‑400 seen at the right. Photographed in Tokyo Bay, perhaps in September 1945. The large, bullet-shaped structures on the forward decks of both submarines are the outer access doors to the aircraft watertight hangars. Clearly scene on the I‑400 is the 85 foot/26 meter compressed-air catapult mounted on the forward deck that launched the sub’s 3 Aichi M6A Seiran attack floatplanes.

Japan Builds Secret Weapon: Aircraft-Carrying I 400–Class Super Submarine

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click