JAPAN ADOPTS “ABSOLUTE DEFENSE PERIMETER” STRATEGY

Tokyo, Japan • September 30, 1943

On this date in 1943, at the fourth Imperial Conference held since the start of the Pacific War, senior Japanese military and civilian leaders adopted the “absolute defense perimeter” strategy after securing the requisite imprimatur of Shōwa Emperor Hirohito. The strategy reflected a shift in the expectations of both the emperor and Japan’s military leadership in light of the accelerating reverses suffered by Japanese armed forces since the naval disaster at Midway (June 3–7, 1942). That was when Japanese hopes were dashed for a second demoralizing American defeat (the first had occurred on December 7, 1941), a defeat intended to force the United States to capitulate in the Pacific War and thus ensure Japan’s dominance of the Western Pacific ocean. In a meeting at Imperial Headquarters on December 31, 1942, staff was advised that the emperor now feared that Japan might lose the war.

In the spring of 1943, Hirohito shared his thoughts with a few imperial court intimates about continuing the war and about pushing for an early conclusion of hostilities. The late May loss by suicidal attacks of the entire Japanese garrison at Attu in the North American Aleutian Islands was a hinge moment in Hirohito’s thinking: from June 8, 1943, the emperor began insisting that his army and navy coordinate joint operations in a single decisive frontal attack in the Pacific so that Japan could claim a victory over the U.S. before negotiating favorable peace terms with the Allies.

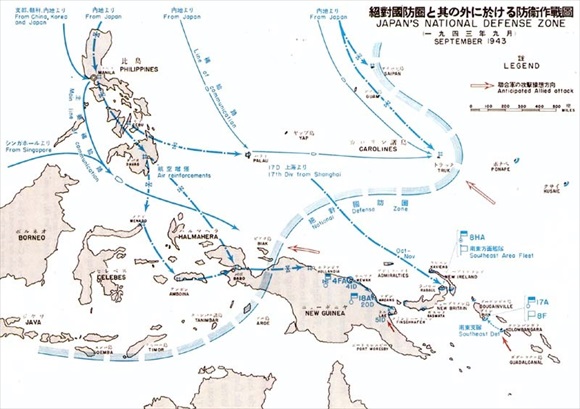

The “absolute zone of national defense” agreement of September 30, 1943, turned its back on Japanese expansion in the Pacific to one of holding the line. The strategy called for Japan’s armed forces to maintain the 1943 front lines until they could rebuild their strength for a final decisive battle in mid-1944. The strategic southern perimeter, to be strongly manned and fortified, ran from Western New Guinea to the Mariana Islands via the Carolines (see map). Defense preparations behind the line were to be completed by the spring of 1944.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, the national defense zone was overrun before it was ever completed. By November 1943 U.S. Adm. William Halsey’s forces, operating from Guadalcanal (evacuated by the Japanese the previous February), had advanced up the Solomon chain as far as Bougainville (right bottom corner of map). Two months later Allied forces had reached Cape Gloucester on the western end of New Britain Island, virtually completing the outflanking of the Japanese stronghold of Rabaul at the eastern end (identified by the long blue arrow outside the defense zone). U.S. and Australian forces raced to the western end of New Guinea by mid-1944, forcing the Japanese to retreat westward to the Dutch East Indies. In October, with the southern periphery of Japan’s National Defense Zone in tatters, Gen. Douglas MacArthur invaded the Japanese-held Philippines. That move provided Halsey’s fleet with the opportunity to sink most of the remaining major Japanese surface ships at the Battle of Leyte Gulf (October 23–26, 1944), forever depriving Hirohito and his armed forces of a favorable site for any decisive showdown with the United States.

![]()

Whittling Away at Japan’s National Defense Zone in the Pacific

|

Above: The southern periphery of Japan’s outer ring of defense in the Pacific, September 1943. The southeast sector was deemed of vital importance to the strategic national defense of the Japanese homeland, its southern boundary to be fixed, behind which air, naval, and ground strength could be replenished and marshaled for a decisive victory over the Americans and their allies. Victory eluded the Japanese in a series of military defeats and retreats in the Pacific and Southeast Asia due partly to the intensifying rivalry between the Japanese Army and Navy and partly to the application of superior Allied resources.

|  |

Left: Japanese transports Hirokawa Maru and Kinugawa Maru beached and burning after a failed resupply run to Guadalcanal on November 15, 1942. The Battle of Guadalcanal (August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943) was the first major ground offensive by Allied forces against Japan. Japanese loses numbered over 19,000 dead, 38 ships, and between 680 and 800 aircraft.

![]()

Right: Heavily laden advance guards of the U.S. 1st Marine Division hit 3 feet/0.9 m of rough water as they leave their landing craft to take the beach at Borgen Bay northeast of Cape Gloucester, New Britain, Territory of New Guinea, December 26, 1943. The Battle of Cape Gloucester took place between late December 1943 and April 1944 and cost the lives of 310 Americans and 1,000 Japanese. The battle was 1 of 10 subordinate operations in Operation Cartwheel, the chief Allied strategy in the Southwest Pacific Area and Pacific Ocean Areas during 1943–1944.

|  |

Left: The deck of this landing craft is closely packed with motorized fighting equipment en route for the invasion of Cape Sansapor, Western (Dutch) New Guinea. The Battle of Sansapor (July 30 to August 31, 1944) was an amphibious landing and subsequent operations around Sansapor. The battle, costing 14 U.S. killed versus 385 Japanese killed and 215 captured, was one in a series of actions during the Western New Guinea Campaign (April 22, 1944, to August 15, 1945). Gen. MacArthur’s last point of landing en route to retaking the Philippines was at Sansapor.

![]()

Right: Making a dramatic entrance, Gen. Douglas MacArthur and staff, accompanied by Philippine president Sergio Osmeña (left in pith helmet), wade through surf onto Red Beach (Palo Beach just south of Tacloban), Leyte, on October 20, 1944, shortly after the start of the Battle of Leyte (October 17 to December 26, 1944). Once on shore MacArthur spoke into a microphone, reading his prepared text with great emotion: “People of the Philippines, I have returned! By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil—soil consecrated in the blood of our 2 peoples. . . The hour of your redemption is here.” The battle for Leyte, one of the larger islands of the Philippines, cost the U.S. just over 3,500 killed and 12,000 wounded. Japanese dead were roughly 49,000.

War in the Pacific: U.S. Army’s “Big Picture,” Part Two, June 1944–1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click