IWO JIMA UNDER U.S. AIR ASSAULT

Saipan Island, Northern Marianas • January 7, 1945

In early October 1944, nearly 3 years into the Pacific War, the U.S. high command decided that, after securing the Philippine island of Leyte (done before the end of December), Gen. Douglas MacArthur was to liberate neighboring Luzon Island, while Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz, from his station in the Central Pacific, would attack the Japanese-held island of Iwo Jima, 8 square miles/21 square km of steaming, sulfurous, volcanic rock located 675 miles/1,086 km from the Japanese capital, Tokyo (see map). The capture of Iwo Jima would be followed up by an attack on the island of Okinawa 950 miles/1,529 km to the northwest. Okinawa was mid-positioned in the Ryukyu Island chain some 325 miles/523 km from the southernmost Japanese home islands and presented itself as a potential forward base for land, air, and naval formations in the invasion of Japan.

On this date, January 7, 1945, the U.S. Seventh Air Force sent 11 B‑24 Liberators from Saipan Island in the western Pacific Ocean to pummel and destroy the 3 enemy airfields on Iwo Jima. (One of the 3 was under construction.) Since the start of the year, more than 130 aircraft from Saipan and Guam had bombed Iwo Jima day and night. Typically comprising less than 20 aircraft, daylight missions clobbered airfields, antiaircraft positions, and radar sites. Nighttime harassment missions, or snooper (radar-assisted bomb release) missions, comprised half that.

The island’s Japanese defenders, with their fighters and bombers, posed serious problems for XXI Bomber Command’s fleet of long-range B‑29 Superfortresses; for example, bombing U.S. bases on Saipan and sending advance warning to the home islands every time Superfortresses passed overhead. At least 39 more days of bombing runs would take place before Operation Detachment, the conquest of Iwo Jima, began on February 16, 1945, when fire-support vessels and carrier aircraft began a 3‑day pre-landing bombardment of the pork-chop-shaped island. U.S. Marines would face over 21,000 armed, well-trained, and well-led Japanese soldiers and marines sheltered in a vast spider web of caves, tunnels, and hidden reinforced concrete fortifications, blockhouses, pillboxes and dugouts nearly impervious to U.S. air and naval bombardment. For nearly 40 days, Iwo Jima became the most bitterly contested spot on the planet, a place of death for 6,821 Americans and some 20,000 Japanese. The significance of the American victory meant that beginning April 7 P‑51 Mustang fighter escorts based on Iwo Jima would accompany B‑29s from the Marianas on their deadly mission to end Japan’s ability to continue the war.

![]()

Iwo Jima, Japanese Citadel Protecting the Homeland

|

Above: Location of Iwo Jima midway between Tokyo (675 miles/1,086 km to the north) and the Mariana Islands (Saipan, 650 miles/1,046 km to the southeast). Enemy aircraft from Iwo Jima were able to bomb U.S. B‑29 bases in the Marianas. Also, Iwo Jima radio operators were able to send 2 hours advance warning to the Japanese home islands every time B‑29s passed north overhead, as well as garner advance notice of U.S. air strikes directed at Iwo Jima itself.

|  |

Left: The battleship USS New York uses its 14 in/35.5 cm main guns to bombard Japanese defenses on Iwo Jima, February 16, 1945. Eight months earlier, starting on June 15, 1944, the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Air Forces began naval artillery shelling and aerial bombings against Iwo Jima that would become the longest and most intense conflict in the Pacific theater. The cataclysmic bombardments and aerial bombings continued through February 19, 1945, the first day of U.S. Marine Corps amphibious landings.

![]()

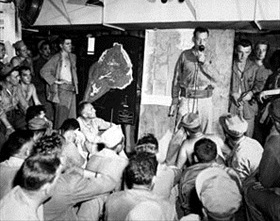

Right: A Marine lieutenant discusses the overall importance of seizing Iwo Jima at a pre-invasion briefing aboard ship. On February 19, 1945, the first of nearly 30,000 U.S. Marines from the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Marine Divisions invaded the tiny volcanic island, less than a third the size of New York’s Manhattan Island, in what was supposed to be a 10‑day battle against 9,000 Japanese. About 40,000 more Marines would follow. Over the next 35 days, approximately 26,000 combatants died or went missing, including 20,000 Japanese and 6,821 U.S. Marines and sailors, making Iwo Jima one of the costliest battles of World War II.

|  |

Above: U.S. Marines going ashore on Iwo Jima, February 19, 1945. Photos made by a U.S. Navy photographer who flew over the 450‑ship armada. Marines, who began landing on the south end of the island at 8:59 a.m., said the island looked like it was on fire due to the preceding 3‑day naval bombardment. The initial wave was not hit by Japanese fire for some time. Only after the front wave of Marines reached a line of Japanese bunkers defended by machine gunners did they take hostile fire. Many concealed Japanese bunkers and firing positions opened up, and the first wave of Marines took devastating losses from the machine guns.

|  |

Left: With Mt. Suribachi, an extinct volcano, looming 554 ft/169 m above the 6 invasion beaches, tracked landing vehicles (LVTs), jam-packed with 4th Marine Division troops, approach Iwo Jima at H‑hour on L‑Day (landing day), February 19, 1945. Inside 2 weeks two-thirds of the infantrymen who were put ashore on L‑Day were casualties. Three weeks later, on March 26, 1945, at the conclusion of the Battle of Iwo Jima, 9,098 of the original 24,452 officers and enlisted men of the 4th Marine Division were either dead or had been wounded.

![]()

Right: Men of the 5th Marine Division inched their way up the volcanic sand slope toward Mt. Suribachi at the south end of the island as smoke from the battle drifted above them, February 19, 1945. The first minutes of fighting took a terrifying toll on the Marines. From their beachhead they could not see where the Japanese, who were heavily dug in and fortified, many in bunkers and caves, were hiding. Marines ran 2 miles/3.2 km across the open beach while taking heavy machine-gun, mortar, rocket, artillery and rifle fire—long ago zeroed-in to create a deadly blanket of fire. Weighed down with over 20 pounds/9 kg of gear, running across the soft, yielding volcanic sand was an unimaginable horror—like running through thick, fire-raked molasses. Seven hundred and sixty Marines made a near-suicidal charge across to the other side of the island on the first day. By that evening the 554‑ft/-169‑m-tall Japanese citadel, with its heavy artillery behind reinforced steel doors, had been cut off from the rest of Iwo Jima.

|  |

Left: U.S. Marines encountered intense artillery fire from enemy positions, February 19, 1945. Japanese troops under their commander on Iwo Jima, Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, were responsible for the deaths of a third of all U.S. Marines killed during the entire 4‑year Pacific conflict. Twenty-seven Medals of Honor were awarded to Marines and sailors, many posthumously, more than were awarded for any other single operation during the war.

![]()

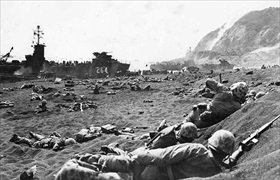

Right: Members of the 23rd Marines’ 1st Battalion, 4th Marine Division burrow into the black volcanic sand on Yellow Beach 1, while their comrades unload supplies and equipment from LSTs (landing vessels) despite being pounded by heavy artillery fire from enemy positions in the background. Their initial objectives were Airfields No. 1 and No. 2. Based on the LSTs shown on the beachhead, this photo was taken on either the February 21 or 22, 1945.

U.S. Government Film Circa 1945 Titled “To the Shores of Iwo Jima”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click