ITALIANS FORM NATIONAL LIBERATION COMMITTEE

Rome, Italy • September 9, 1943

On this date in 1943 in Italy, the Allies from their strongholds in North Africa (since November 1942) and Sicily (since July‑August 1943) invaded the boot-shaped Italian mainland at Salerno, some 170 miles/274 km southeast of Rome, Italy’s capital, with diversionary landings at Reggio di Calabria (September 3, 1943), which lay on the “toe” of the Italian Peninsula, and Taranto (September 9), the Italian naval port and airfields that lay in the “instep” of the Italian heel. The Salerno landings came 6 days following Italy’s secret armistice with the Allies on Sicily on September 3, 1943 (the armistice of Cassibile, or short armistice, was publicly announced 5 days later), and the flooding of thousands of German troops and equipment into Italy the previous month in the wake of Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini’s arrest and imprisonment in late July of the same year by forces loyal to King Victor Emmanuel III. In landing on the Italian mainland U.S. forces were returning to the European continent for the first time since 1918.

On the same date, September 9, 1943, 6 major Italian anti-fascist parties formed the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (CLN), or National Liberation Committee, to organize the country’s unified resistance to Nazi Germany’s occupation of Italy. To organize and foster cooperation with the Western Allies, the CLN met with representatives of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and the military intelligence services of both countries, MI9 and MIS‑X, respectively.

From heavily fortified positions the Germans sent out armored patrols to round up Italian Resistance fighters and partisans (partigiani in Italian) and to take brutal reprisals against the local population if any partisans or their sympathizers were found hidden in their villages or towns or were suspected of engaging in sabotage or hit-and-run operations against German troops and convoys. During the course of the Italian civil war (September 1943 to April 1945) the dead included 50,000 members of the Italian Resistance (not all Resistance fighters were Italian-born) and on the other side 35,000 troops of Mussolini’s Nazi puppet state, the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (Italian Social Republic, or simply Salò Republic). In summer 1944 alone, German casualties fighting partisans amounted to 20,000; the figure included 5,000 killed, 7,000–8,000 missing/”kidnapped,” and a similar number seriously wounded. Between July 1943 and May 1945 total estimated German casualties and losses in Sicily and mainland Italy vary from 366,000 to just over 580,000. During the same period 150,000 or more non-combatants died, many in revenge killings that occurred at the end of hostilities and in their immediate aftermath.

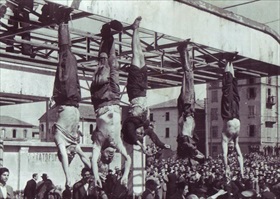

On April 19, 1945, the CLN called for an insurrection. In Northern Italy Bologna was attacked by partisans on April 19 and liberated on April 21 by the Italian Co-Belligerent Army, the army of the Italian Royalist forces fighting on the side of the Allies, together with the Polish II Corps under Allied command. Turin and Milan were liberated on April 25 through an insurrection following a general strike that commenced 2 days earlier; over 14,000 German and Fascist troops were captured in Genoa on April 26–27. Many of the defeated German troops attempted to escape from Italy and some partisans units allowed the German columns to pass through if they turned over any Italians who were traveling with them. Such was the fate of Benito Mussolini, who, along with his mistress and several fascist big-wigs, was captured and executed on April 28, their bodies taken to Milan and hung from a girder at a gasoline station in city’s Piazzale Loreto (see photo essay below). On May 2, 3 days after the suicide of Mussolini’s German comrade-in-arms, Adolf Hitler, in his underground Fueherbunker in the Nazi capital, Berlin, enemy occupation forces in Italy officially capitulated to the Allies. Some die-hard fascists attempted to continue fighting, but they were quickly suppressed by Italian partisans and Allied forces.

A People in Arms: Tragic Fallout from Germany’s Military Occupation of Italy, September 1943 to April 1945

|  |

Left: Italians shot by Germans on a street in Barletta, an Adriatic city in Southern Italy, on September 12, 1943, 9 days after the British amphibious and airborne invasion of Southern Italy (Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery commanding) and 3 days after the September 9 Anglo-American landings under Lt. Gen. Mark Clark of the U.S. Fifth Army in and around Salerno on the west coast of Italy.

![]()

Right: A woman hanged by fascists in Rome, surrounded by German soldiers, sometime in early 1944 before elements of Mark Clark’s Fifth Army entered Rome on June 5, 1944. A white sign pinned to the front of her skirt laid out the charges for which she was summarily executed.

|  |

Left: The Nazis and their fascist stooges in the besieged and ever-shrinking Salò Republic adopted a reprisal policy meant to split the populace from the partisans: 10 Italians killed for every German and fascist death. Mass atrocities like the Ardeatine massacre outside Rome (335 Jews and political prisoners) and the Stazzema massacre of about 560 Tuscan villagers, of which 130 were children, were notorious standouts. This photo from August 1944 shows 3 partisans executed by public hanging at Rimini on the Adriatic coast. By then partisan strength stood at 100,000, swelling to 250,000 in April 1945. The partisan family of Alcide and Genoneffa Cervi, living in Reggio Emilia northwest of Rimini, lost all 7 sons to a fascist reprisal the previous December. Later that same month the fascists attacked the Cervi farm, torching the family’s barns. Genoneffa Cervi suffered a fatal heart attack that same day, leaving her 2 daughters and husband the sole survivors of fascist retaliations. After the war the Italian president pinned 7 silver medals for military valor on Alcide Cervi’s chest, one for each of his lost sons.

![]()

Right: Displayed in the Piazzale Loreto, Milan’s major town square, on April 29, 1945, are the grime-covered corpses of Benito Mussolini (second from left) and to the right his 33‑year-old mistress, Claretta Petacci, along with the remains of other executed fascists, primarily ministers and officials of Mussolini’s Nazi puppet state, the Salò Republic. Mussolini was shot through the forehead near the village of Dongo on Lake Como near the Swiss border late the previous afternoon after his German convoy was stopped and searched by partisans. His body was taken in a closed van to Milan, the city where Italian fascism was born in 1919, and dumped in the same spot where the year before fascist squads had exhibited the bodies of 15 Milanese civilians (the so-called “Martyrs of Piazzale Loreto”) whom they had killed in retaliation for partisan activity. A howling mob of more than 5,000 people kicked and spat on Mussolini’s remains before his corpse was hung upside down on butcher hooks at a gas station, where it remained for several days before being removed and buried. In 1957 Mussolini’s remains were reinterred in Predappio, his birthplace in the Appennine Hills of Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region. His tomb attracts thousands of far-right pilgrims from across Italy and beyond, especially on the anniversary of his death.

Student Documentary: The Rise of Italian Fascism, Italian Resistance Movement, and Italy’s Liberation

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click