HUGE NAVAL BATTLE IN CORAL SEA

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea • May 4, 1942

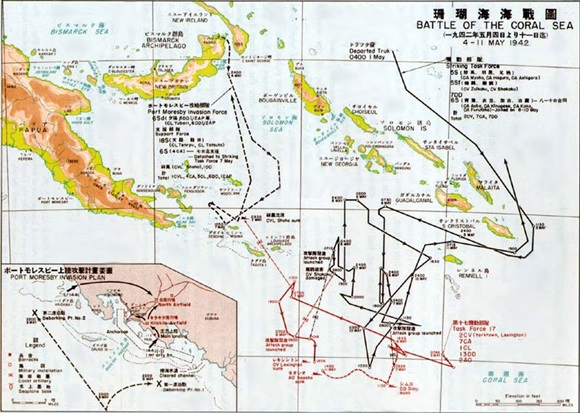

On this date in 1942 the five-day Battle of the Coral Sea began. A Japanese invasion fleet of five troop transports and seven destroyers from their bastion of Rabaul on the island of New Britain, in concert with a Japanese carrier force from Truk (Chuuk) in the Central Pacific, was steaming toward the capital of Australian Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby, which had the potential of becoming, after Rabaul’s audacious capture earlier in January, another major Japanese staging point and air base in the South Pacific (see dotted line on map below). If the Japanese gained an advance base in Papua New Guinea, they would strengthen their defensive position and sever the U.S. West Coast-Hawaii-Australia lifeline, and their aircraft would be within striking distance (1,124 miles) of Darwin, Northern Australia, a strategic port and air base for the Allies.

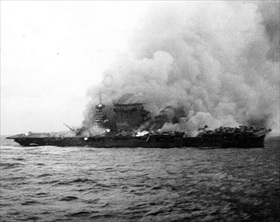

Naval and air force units from the United States and Australia, under the overall command of American Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher, set out to stop the Japanese. The resulting engagement southwest of the Solomon Islands was the first of five carrier versus carrier sea battles in naval history and the first naval battle in which two opposing fleets were never in visual contact. Separated by 175 miles of ocean, the fleets battled each other with their carrier aircraft. The losses were about equal on both sides: the U.S. lost its first carrier of the war, the 888-ft-long fleet carrier Lexington, Japan the heavy cruiser Mikuma and the light carrier Shōhō, the first enemy carrier to be sunk in combat. Still, it was the first time the Japanese had experienced failure in a major operation. That in itself gave the Americans a huge morale boost following the inevitable loss of the last U.S. garrison, Corregidor (May 5–6, 1942), in enemy-held Philippines. Furthermore, the damage the Allies inflicted on the big Japanese fleet carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku prevented the sister flattops from participating in the Battle of Midway the following month (June 4–7, 1942). That pivotal battle was a clear-cut victory for the U.S. Navy, and the initiative, both at sea and in the air, now lay squarely with the Americans.

But not on land. The Japanese still attempted to take Port Moresby, viewed as a threat to their naval and ground operations in the Bismarck and Solomon Seas, via the mountainous Kokoda Track (July 1942 to January 1943), staging from Buna and Gona on the northeast coast of the island. During the New Guinea campaign (January 1942 to August 1945), more than 33,000 Americans and Australians fought the Japanese, suffering a casualty rate of 1 in 11. The U.S. 2nd Battalion/126th Infantry Regiment (nicknamed “Ghost Battalion”) was especially hard hit. Out of 1,400 men who went into action on November 21, 1942, only six officers and 126 troops were standing when Buna was retaken six weeks later. By comparison, 60,000 Americans fought the Japanese on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands (August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943), where 1 in 37 GIs died.

Sea and Land Campaigns in the Southwest Pacific, 1942–1943

|

Above: Map showing the movements of the Japanese Port Moresby seaborne assault force (dashed lines in center) and the plan for the force’s landing (bottom left corner), which the Japanese called “Operation Mo.” The sinking of the light carrier Shōhō, which took 600 of her 800 crewmen to their graves, together with the battering the carrier Shōkaku received prompted the Japanese to recall the Port Moresby invasion force back to its starting point, Rabaul. Port Moresby, on the southeastern coast of the Papuan Peninsula of the island of New Guinea, was the last Allied base between Australia and Japan. The map also depicts the naval Battle of the Coral Sea, May 4–8, 1942 (solid lines in right half). With Japan’s failure to capture Port Moresby, the invasion threat to Northern Australia disappeared.

|  |

Left: U.S. fleet carrier Lexington burning after her crew abandoned ship during the Battle of the Coral Sea, May 8, 1942. Some 216 crewmen were killed and 2,735 evacuated. The “Lady Lex” sustained numerous hits from Japanese carrier aircraft. However, it was a series of massive explosions initially set off by sparks that ignited gasoline vapors from ruptured fuel tanks that proved fatal to the flattop. The Lexington was sent to the ocean floor after Rear Adm. Fletcher ordered a U.S. destroyer to torpedo the flaming wreck.

![]()

Right: Three members of the U.S. 32nd Infantry Division move supplies by boat on the Girau River on New Guinea’s northeast coast near enemy-held Buna Mission sometime in late 1942. (The 32nd was the first complete American division, consisting of 12,000 men and equipment, to reach the Southwest Pacific Area.) The jungle was so thick that “in the dark, live Americans bumped into live Japs,” wrote combat photojournalist George Strock for LIFE magazine, while daylight would reveal “dead Americans . . . alongside dead Japs.” With no roads through the jungle-clad island, the only way to keep Allied troops furnished with the food, ammunition, and other goods necessary to operate against the Japanese was via water and airborne supply.

|  |

Left: Three GIs lie dead on Buna Beach near a wrecked landing craft. This image by LIFE magazine’s George Strock taken in February 1943 was not published until September 20, 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized its release, the first image to depict American soldiers dead on a battlefield. (U.S. military censors placed no restrictions on photos of enemy war dead.) FDR was concerned that the public was growing complacent about the cost of the war on American lives.

![]()

Right: Australian forces attack Japanese positions near Buna, January 7, 1943. Members of the 2/12th Infantry Battalion advance as Stuart tanks from the 2nd Battalion/6th Armored Regiment attack Japanese pillboxes. An upward-firing machine gun on the tank sprays treetops to clear them of snipers.

Battle of the Coral Sea, May 4–8, 1942: An Australian Tribute

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click